MCGILL UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF URBAN PLANNING

Abstract

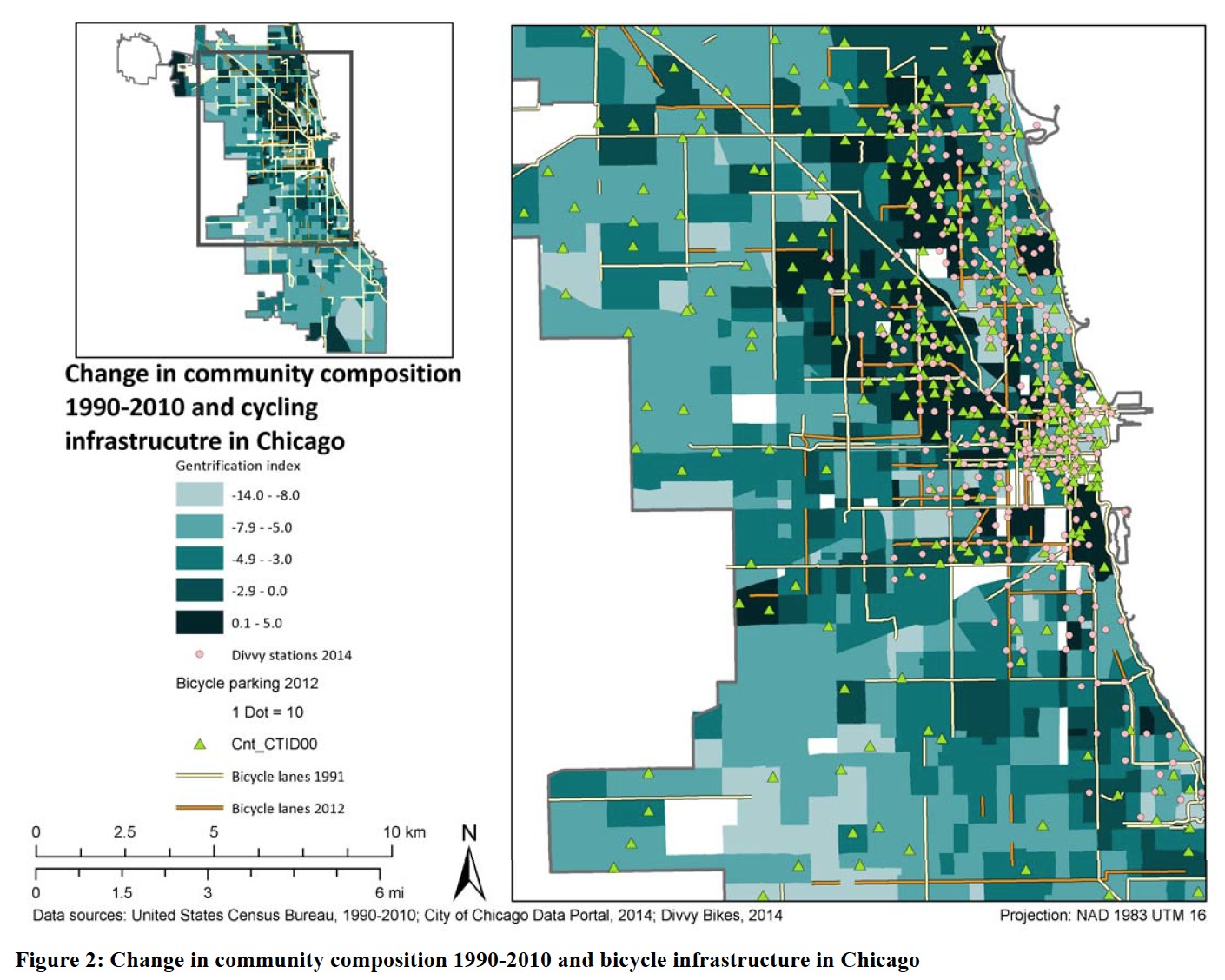

Bicycles have the potential to provide an environmentally friendly, healthy, low cost, and enjoyable transportation option to people of all socio-economic backgrounds and demographics. Increasingly, however, the ways in which cycling culture is manifested in North American cities is being questioned on the grounds of transportation equity through concerns over gentrification and the cooption of cycling culture to promote the agendas of the privileged class. This research assesses the geographic distribution of cycling infrastructure with regard to community demographic characteristics to better assess claims that cycling investment arrives in tandem with incoming populations of privilege or is targeted towards neighborhoods with existing wealth. Using census and municipal cycling infrastructure data in Chicago and Portland from 1990 to 2010, we create gentrification and cycling infrastructure investment indexes at the census tract level. Linear regression models are used to estimate the extent to which community demographics associated with gentrification and cycling infrastructure investment are related and if community change is a major driver in investment or if existing community characteristics are also involved. In both cities, we identify a bias towards increased cycling infrastructure investment in areas of privilege, whether due to an increase in characteristics associated with gentrification or pre-existing conditions. This paper provides evidence that marginalized communities are unlikely to attract as much cycling infrastructure investment without the presence of privileged populations, even when considering population density and distance to downtown, two motivators of urban cycling. To alleviate the continuation of inequitable distributions of cycling investments, it is proposed that planning processes both actively seek out diverse stakeholders and be sensitive to citywide community input and stated needs in future transportation projects, contributing to reinvestment achieved through bottom-up processes of revitalization rather than through the impositions of gentrification.

Introduction

Bicycles have great potential to be an equitable, healthy and sustainable mode of transportation. Cycling infrastructure, including lanes, parking, or bicycle share programs, can help foster a safe and inviting environment where users of all abilities have high access to opportunities and services. Yet cycling advocacy is increasingly being critiqued from an ethical perspective. Blog articles such as: Are Bike Lanes Expressways to Gentrification? (1) and On Gentrification and Cycling (2) point to the perception in non-academic literature of mainstream cycling as a White affluent male activity, and describe how low-income and minority communities see cycling culture as accompanying processes of rising living costs, displacement, and the undermining of established local cultures during processes of gentrification. Recent academic papers, such as those by Hoffman and Lugo (3), Lubitow and Miller (4) and Stehlin (5), discuss underlying socio-political factors associated with gentrification, “White” cycling culture, and ongoing inequities in urban transportation networks and decision-making processes (3-5).

We empirically assess these claims by exploring relationships between the distribution of cycling infrastructure investment and community demographic characteristics in Chicago, IL and Portland, OR.

We begin by outlining the limited empirical evidence of cycling infrastructure investment mirroring gentrification and privilege in the literature. Next, we use census tract and municipal cycling infrastructure data from 1990 to 2010 to create gentrification and cycling infrastructure investment indexes. The years 1990 and 2010 are chosen for analysis to take advantage of census demographic data over a time period long enough to capture changes in community composition. However, this large grain of data makes interpretations of whether cycling infrastructure is a cause or effect of changing community characteristics impossible. Linear regression models provide evidence that cycling investment is related to both privileged current demographics and to markers of gentrification. Given the economic and health benefits of this transportation, we conclude with the need to balance investments and provide strategies to mitigate the continuation of investment disparities. Because this topic deals to a large degree with community perceptions of cycling and gentrification, there is a focus in the literature review on capturing the words and narratives of individuals who are not in academia. Newspaper articles and online media point out community views on social processes and serve as the inspiration for this research. Academic literature is drawn on to develop a working definition of gentrification and the analysis methodology.

…

Conclusion

This study of Portland and Chicago reveals disparities in cycling infrastructure investments above and beyond expected differences associated with distance from downtown and density of census tracts. As the models show, there is an association between cycling infrastructure and both gentrification and current privilege. Low-income and communities of color, who would benefit most from increased cycling infrastructure for the economic, health and safety benefits, have been less likely to receive municipal or private investment. Mitigating these disparities in the future will be challenging and require rethinking assumptions about cycling culture and planning processes. Concerted efforts must be made so that investment follow needs and is equitably distributed, while not being imposed. Forcing frustrated communities to accept changes that may seemingly (or actually) disproportionately benefit privileged residents will not build trust in institutions or a safe environment for cycling among all socio-economic groups. Rather, planners should seek to support “revitalization” efforts- bottom-up economic reinvestment- instead of the top-down impositions of economic development through gentrification.

About the McGill University School of Urban Planning

https://www.mcgill.ca/urbanplanning/

The School draws students from around the world. Through our core Master of Urban Planning degree program and an optional concentration in Transportation Planning, we train professionals for the public, private, and not-for-profit sectors in two years of intensive study, much of which takes place in real-life group projects using the Montréal metropolitan region as a living laboratory. Our aim is to give individuals the intellectual and practical skills needed to excel in the field and thereby to improve human settlements around the world.

Tags: Bicycling, Bike Lanes, Chicago, Cycling, Gentrification, McGill University, Portland

RSS Feed

RSS Feed