NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CITY TRANSPORTATION OFFICIALS (NACTO)

In cities that are building protected bike lane networks, cycling is increasing and the risk of injury or death is decreasing. Pairing appropriately-scaled bike share with protected bike lanes increases ridership and is essential to equity and mobility efforts.

The connection between bike share ridership and high-quality bike lanes is clear: people ride more when they have safe places to ride. Less explored is the positive feedback loop between bike share, the creation of protected bike networks, and overall cyclist safety – and the importance of this feedback loop in helping to address the systemic inequities in the U.S. transportation system.

Over the six years from 2010 to 2015, there were over 62 million bike share trips in the United States and zero fatalities; an enviable safety record. There are many explanations for bike share’s safety advantage over general bicycling, but strong evidence is emerging that bike share is a tool for improving the safety of all riders. NACTO’s new analysis of seven major cities across the U.S. shows that, as cities build more bike lanes, the number of cyclists on the street increases, and the individual risk of a cyclist being killed or severely injured drops, often dramatically. The investment in bike lanes spurs additional cycling, increasing visibility and further reducing risk for all cyclists. Deployed across city neighborhoods at a meaningful scale, as NACTO has described in other reports, bike share can help increase overall bike ridership at accelerated rates and spur a city to develop more—and better—bike infrastructure. By increasing the number of people riding, bike share systems can directly make cycling safer for all, including people on their own bikes.

Cities across the country have demonstrated how to kickstart this process. Chicago and New York—like Paris and Montreal before them—began to develop a protected bike lane network years before launching a large bike-share system and subsequently have seen high and sustained bike share use from day one, as users immediately found safe places to ride. Riders in these cities have seen their risk of death or injury from motor vehicles decline steeply. A similar story plays out in Minneapolis—where the bike share system was matched with bike network expansions—and Portland, where the bike network and overall ridership have continued to grow.

These safety gains are particularly important for low-income people and people of color. These groups make up an increasingly large part of the cycling population but often lack protected bike lanes in their neighborhoods. They disproportionately bear the burden of fatalities and injuries from dangerous drivers and poorly designed streets. An analysis from the League of American Bicyclists found that Black and Hispanic cyclists had a fatality rate 30% and 23% higher than white cyclists, respectively, and similar racial/ethnic safety gaps are found for pedestrians. In focus groups and surveys, low-income people and people of color cite concerns about safety and lack of bike lanes as a main reason not to ride.

A myth pervades that people of color do not bike, but the data shows otherwise. Non-white householders in the Portland metropolitan area, for example, bike at a higher rate than white ones. Research conducted for PeopleForBikes in 2014 found that 38% of Hispanic Americans and 26% of Black Americans bike at least once a year and that the number of Black Americans biking increased by 90% from 2001-2009, faster than any other racial or ethnic group. Cycling is also a fact of life in many low-income communities. Analysis of national Census data by the Kinder Institute for Urban Research shows that 49% of the people who bike to work earn less than $25,000 per year. In 2014, PeopleForBikes reported that the lowest-income households—Americans making less than $20,000 per year—are twice as likely as the rest of the population to rely on bikes for basic transportation needs like getting to work.

Ensuring that people have transportation options that are efficient, convenient, and safe is fundamental to efforts to reduce income inequality in the United States today. Indeed, as found in an ongoing Harvard study and reported in the New York Times, “commuting time has emerged as the single strongest factor in the odds of escaping poverty.” Large scale bike share programs are part of the solution: they increase the reach of rail and bus transit, help people make short trips faster and more easily, are cheaper to implement than other transportation options, and cost the user pennies per trip.

But, for bike share to fulfill this role and for its benefits to be equitably distributed, bike share programs must be matched with extensive protected bike lane networks that offer people safe, comfortable places to ride, regardless of income level, ethnicity, or race. Safety benefits from bike share are greatest when cities pair appropriately scaled systems with an extensive protected bike lane network built for people who are “interested but concerned,” strategically place on-street bike share stations in ways that calm traffic, and remove legal and regulatory obstacles to bicycling. Like offering inclusive pricing structures and payment mechanisms,9 or ensuring good service quality by maintaining a walkable distance between stations, providing people access to places to ride where they feel comfortable and safe is essential to larger equity and mobility efforts.

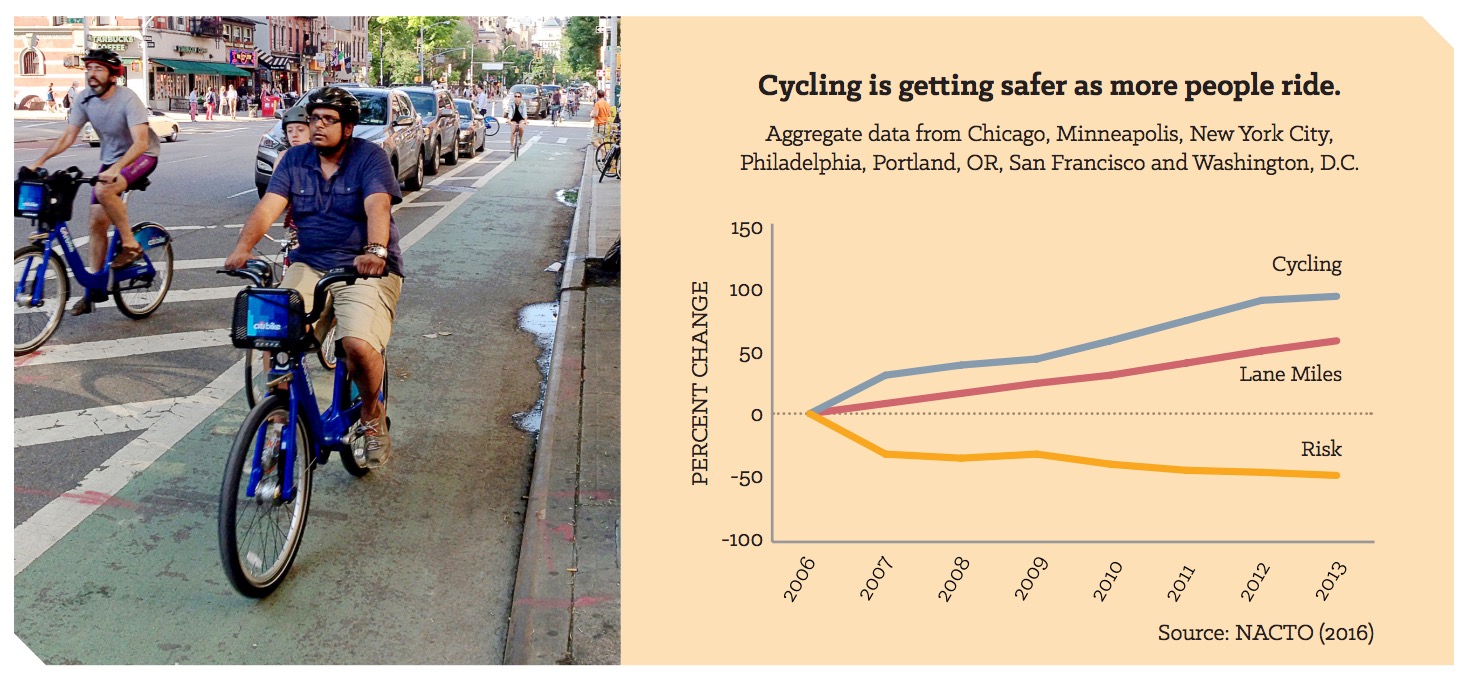

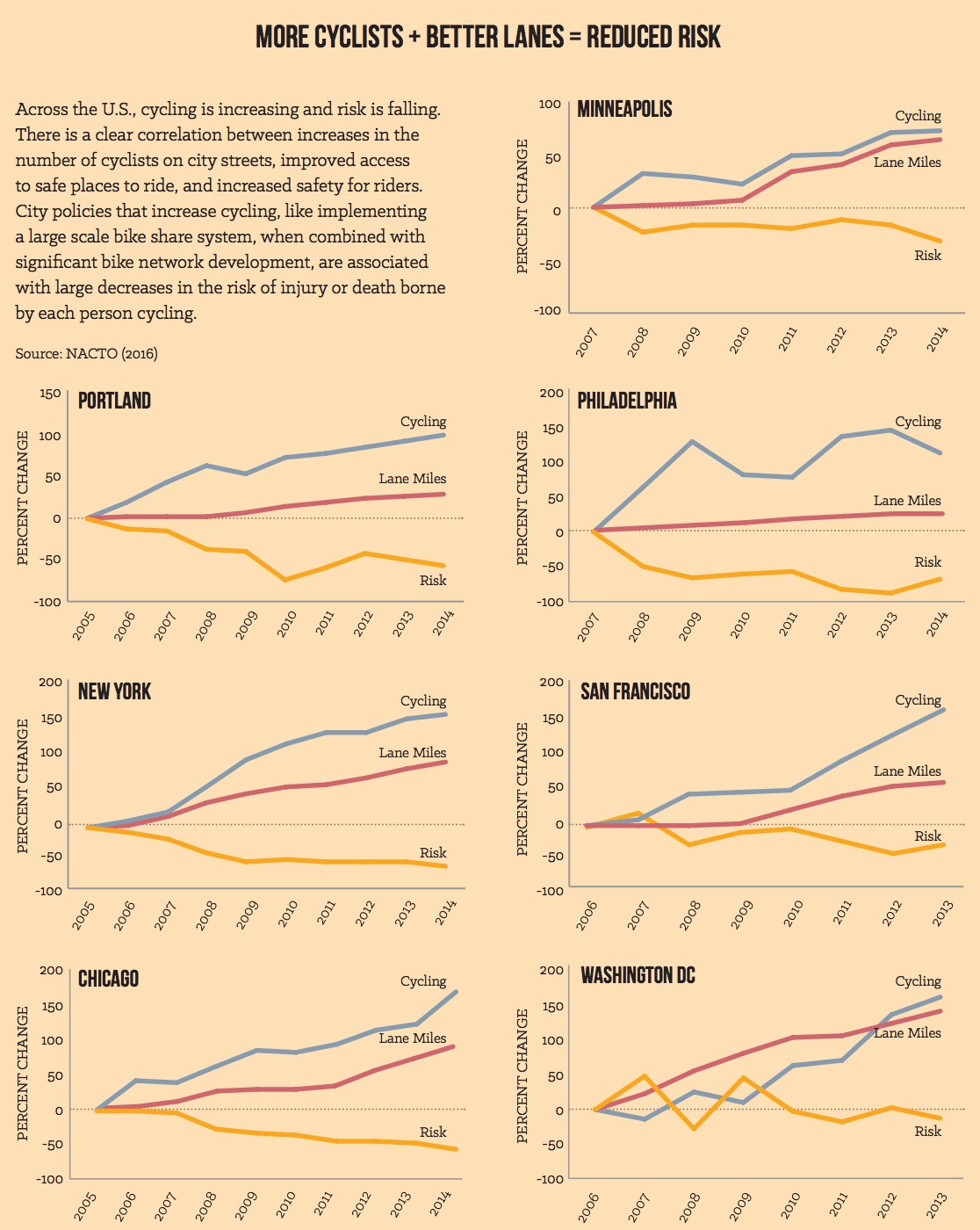

More Cyclists + Better Lanes = Reduced Risk

The combination of increased ridership and more bike lanes is a powerful recipe for safety. For this paper, NACTO collected data from seven cities across the U.S. on bike network mileage, number of cyclists killed or severely injured (KSI), and bicycle volume. The resulting analysis shows that cycling is on the rise in the U.S. and that there is a clear correlation between an increase in the number of cyclists on city streets, growth in the city’s bike lane network, and an improved safety rate for riders. In all seven cities studied, the risk per cyclist decreased as bicycling ridership increased, and the rate of growth in cycling far outstripped the rate of cyclist injuries or fatalities. Municipal policies that increase cycling, like implementing a large scale bike share system, when combined with significant enhancements to bike infrastructure, are associated with large decreases in the risk of injury or death borne by each person cycling.

In particular, New York, Chicago, and Minneapolis have made significant investments to build protected bike networks and their transportation departments have begun to aggressively target high-crash, high-volume locations and corridors. NACTO analysis shows that the risk of injury or death to cyclists in these cities has fallen dramatically from 2007-2014. The work of big cities, like New York and Chicago, is particularly impressive, reducing the risk to cyclists by more than half and bringing the overall cyclist risk rate more closely in line with smaller cities. Investments in cycling, and the resulting safety gains, can be largely credited to strong leadership from mayors and transportation commissioners. Since 2007, New York City has built an average of 54 miles of bike lanes each year, while Chicago has built an average of 27 miles per year since 2011.

Download full version (PDF): Equitable Bike Share Means Building Better Places for People to Ride

About the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO)

nacto.org

The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit association that represents large cities on transportation issues of local, regional and national significance. NACTO views the transportation departments of major cities as effective and necessary partners in regional and national transportation efforts, promoting their interests in federal decision-making.

Tags: Bicycling, Bike Lanes, Bike Share, Bikeshare, Cycling, NACTO, National Association of City Transportation Officials

RSS Feed

RSS Feed