MANHATTAN INSTITUTE

By Aaron M. Renn, Senior Fellow

Executive Summary

The biggest capital project, by far, in many American cities is one that few of their citizens even know about and that almost none has ever seen: the legally mandated retrofitting of “combined sewers,” sewers in which storm-water runoff and sanitary waste from buildings are channeled into the same pipes to reduce or eliminate overflows of untreated wastewater into local waterways.

These combined-sewer projects—whose price tag will run into billions of dollars in some places—represent large unfunded mandates. Although the federal government, via the Clean Water Act, is requiring cities to undertake such projects, the bulk of federal funding for sewers comes in the form of loans that must be repaid: in most cities, local citizens and property owners will pay the vast majority of the costs through higher utility bills, property taxes, and other local funding sources.

These sewer projects will improve local water quality and reduce flooding but will also come with significant negative side effects. Many such projects will be undertaken in postindustrial cities still reeling from population and job losses and struggling to address high poverty levels. Raising sewer rates to pay for expensive combined-sewer overflow remediation will serve as a de facto regressive tax on lower-income households, while rendering such cities even less competitive economically.

To achieve Clean Water Act compliance in a way that minimizes the impact on lower-income residents and on economic competitiveness, these localities require significant assistance, such as support for a more aggressive shift to green infrastructure; modifying sewer rate structures; revisiting EPA affordability guidelines; renewed or enhanced federal and state aid; and redirecting other aid sources to sewer-mandate compliance.

I. Introduction

In the nineteenth century, drainage problems and sanitation and health crises led many cities to develop sewer systems. In 1855, Chicago became the first U.S. city to have a comprehensive sewer system. Boston began building one in 1876.

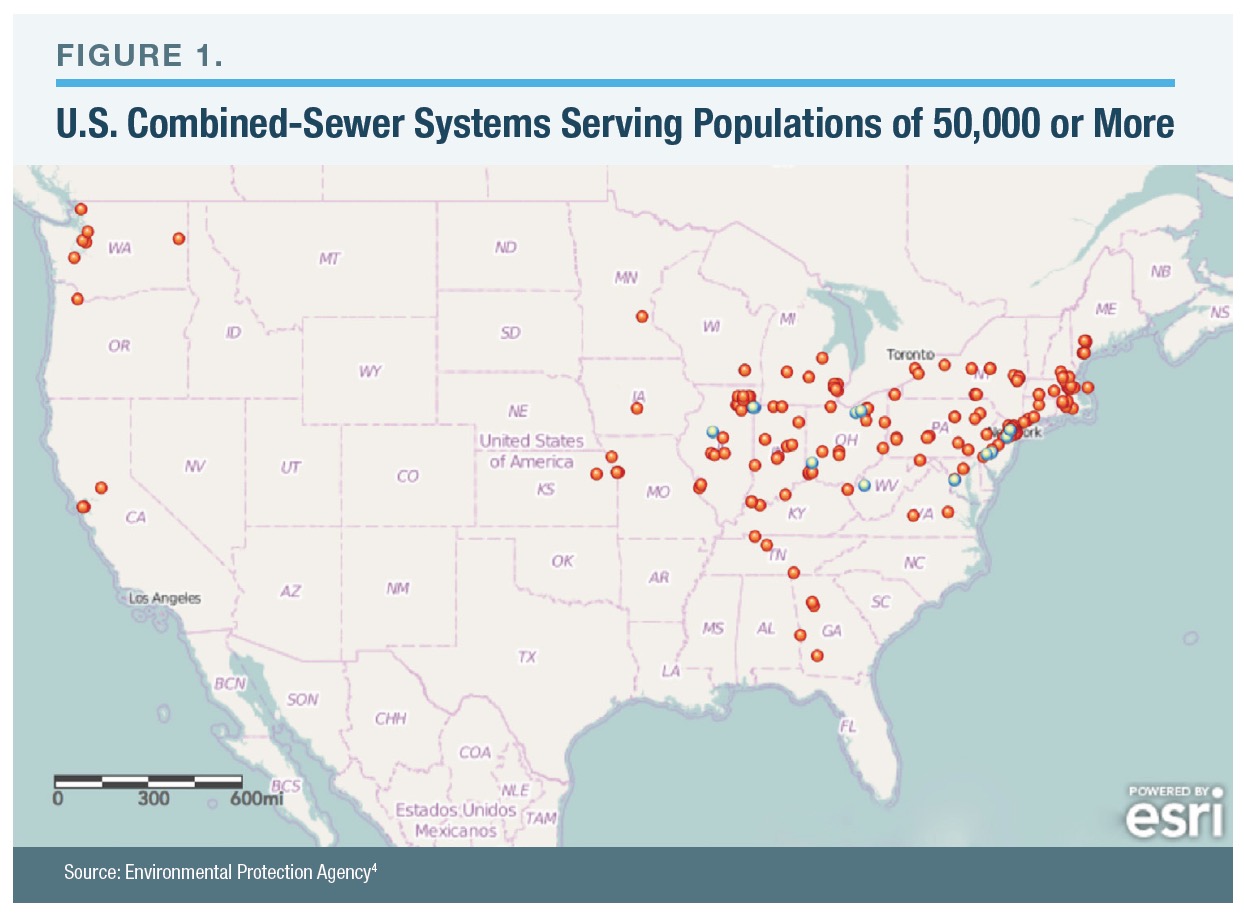

Most of these early systems were built as so-called combined sewers—sanitary wastewater from buildings was combined with storm-water runoff into the same pipe system. The alternative approach, a “separated” sewer system, which uses different pipes for storm-water runoff and sanitary wastewater, was also implemented in the nineteenth century, especially in Europe. But different rainfall patterns made combined sewers more attractive in America. Today, 772 U.S. cities have combined sewers, mostly in the older industrial regions of the Northeast and Midwest (Figure 1).

In the nineteenth century, sewage was not treated, so the choice of piping system did not affect treatment levels, as it would today. Recall, too, that this was the era of horse-drawn transportation: urban streets were full of horse manure and, often, dead animals;5 industrial and stockyard runoff left waterways heavily polluted. For cities with occasional heavy rainfalls that made storm sewers a necessity, it did not make sense to build two sewer systems. For these cities, “dilution was the solution.”

II. Combined-Sewer Overflows and Their Remediation

Ultimately, sewage treatment was added for both combined sewers and the sanitary portion of separated systems. But for cities with combined sewers, there is an additional challenge. Normally, wastewater is treated—and thus is clean—before being discharged into local streams, rivers, and lakes. Heavy rainfall, however, can overwhelm the capacity of combined sewers and treatment systems. In these cases, the sewer systems will overflow, dumping untreated (if diluted) wastewater into local waterways at overflow points—“combined-sewer overflow” (CSO).

The Clean Water Act of 1972 targeted the cleanup of America’s waterways from the legacy of the industrial age, including CSOs. In 1994, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its CSO control policy, which requires cities to substantially eliminate CSOs in order to comply with the Clean Water Act. Though today the human-health impact of CSOs is limited, the federal mandate seeks to make local waterways clean enough for swimming and fishing.

The EPA has since undertaken enforcement actions and sued cities and independent sewer districts across the U.S. for noncompliance: under the “polluter pays” principle of environmental law, such entities are responsible for what were, at the time, legal and appropriate decisions. EPA-enforcement actions have frequently resulted in consent decrees specifying mandated investments to achieve compliance. But even without a consent decree, every city with combined sewers has had to take action to achieve compliance.

Remediation actions vary from place to place, depending on the specifics of the sewer system. Some cities are increasing their treatment capacity; others must upgrade the capacity of sewer lines to transport wastewater to the treatment facility. Some cities are constructing “deep tunnel” projects—large-diameter tunnels bored far underground to store excess wastewater that temporarily exceeds the system’s treatment capacity; others are undertaking separation projects to separate sanitary and storm sewer pipes.

More recently, cities such as Philadelphia have turned to “green infrastructure” solutions, such as bioswales (gently sloping detention trenches with plants that filter and slowly discharge storm water into the ground), in an attempt to reduce storm-water runoff. Green infrastructure can be less expensive to install, can deliver benefits sooner, and can have more ancillary community benefits than traditional solutions. These various approaches to CSO remediation are typically implemented in combination, though the specific mix is unique to each city.

Download full version (PDF): Wasted – How to Fix America’s Sewers

About the Manhattan Institute

manhattan-institute.org

The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research is a leading voice of free-market ideas, shaping political culture since our founding in 1977. Ideas that have changed the United States and its urban areas for the better—welfare reform, tort reform, proactive policing, and supply-side tax policies, among others—are the heart of MI’s legacy. While continuing with what is tried and true, we are constantly developing new ways of advancing our message in the battle of ideas.

Tags: Aaron M. Renn, bioswales, Clean Water Act, EPA, sewers

RSS Feed

RSS Feed