NATIONAL CENTER FOR TRANSIT RESEARCH

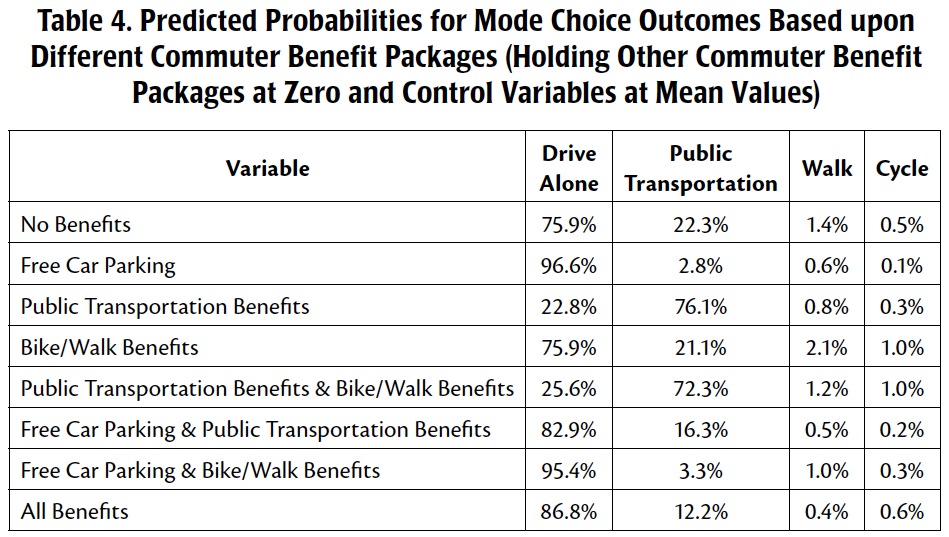

Municipalities and employers in the U.S. attempt to reduce commuting by automobile through commuter benefits for riding public transportation, walking, or cycling. Many employers provide a combination of benefits, often including free car parking alongside benefits for public transportation, walking, and cycling. This study evaluates the relationship between commuter benefits and mode choice for the commute to work using revealed preference data on 4,630 regular commuters, including information about free car parking, public transportation benefits, showers/lockers, and bike parking at work in the Washington, DC region. Multinomial logistic regression results show that free car parking at work is related to more driving. Commuters offered either public transportation benefits, showers/lockers, or bike parking, but no free car parking, are more likely to either ride public transportation, walk, or cycle to work. The joint provision of benefits for public transportation, walking, and cycling is related to an increased likelihood to commute by all three of these modes and a decreased likelihood of driving. However, the inclusion of free car parking in benefit packages alongside benefits for public transportation, walking, and cycling, seems to offset the effect of these incentives. Benefits for public transportation, walking, and cycling, seem to work best when car parking is not free.

Introduction

Travel demand management (TDM) objectives include congestion mitigation, conservation of financial and energy resources, pollution reduction, and improvement in health outcomes and quality of life measures (Cervero 1991; Giuliano 1992; TCRP 2002, 2010; FHWA 2012b). At the local and regional levels, planning authorities have begun to implement policies to achieve TDM objectives and increase travel by public transportation, cycling, and walking, including changes to parking fee structures and requirements, zoning ordinances, building codes, and roadway regulations (TCRP 2010).

Another important policy tool to achieve TDM objectives has been the creation and expansion of commuter benefits—although the types and levels of these benefits has varied across both modes and time (Potter et al. 2006; TCRP 2003; EPA 2007; IRS 2013). Free car parking, however, generally continues to be the most prevalent type of benefit offered to commuters; only about 5 percent of auto commuters pay for parking in the U.S., and commuters, on average, avoid direct payment of the majority of actual parking costs (Wachs 1990; Shoup 2005; TCRP 2005; FHWA 2012a).

The interaction effects among commuter benefits have received relatively little attention in the literature, and few commuter mode choice studies jointly include benefits for driving, public transportation, and walking or cycling. However, the importance of policy interactions relating to travel behavior has long been recognized. For example, Pucher (1988) conducted an international comparison of transportation policies, and argued that public transportation benefits in the U.S. are largely rendered ineffective in the absence of complementary automobile taxation policies.

More recently, Washbrook et al. (2006) conducted a study of the effect of road pricing and parking charges on commuter mode choice in Vancouver, Canada, and concluded that effective TDM requires a combination of disincentives for driving and incentives for walking, cycling, and public transportation. Similarly, Habibian and Kermanshah (2011) highlight the push and pull factors for the decision to drive. Also, Marsden (2006) reviewed the literature on behavioral responses to various parking policies and suggested that substantial mode shifts among commuters may be achieved when a package of alternatives is introduced along with changes to car parking pricing or supplies.

It remains a question whether, at the level of the individual commuter, packages that offer benefits for driving as well as walking, cycling, and public transportation may effectively promote TDM objectives. This study attempts to address that question and the growing need for understanding the cumulative effects of commuter benefits on travel behavior.

Until recently, commuter benefits for cycling and walking were often omitted from studies regarding transportation mode choice—typically due to their omission from data collection efforts as well as their relatively low level of provision. This study contributes to the literature through the inclusion of commuter benefits for driving, riding public transportation, and walking or cycling to work. In addition, this paper also supplements the existing literature on commuter benefits and mode choice by utilizing revealed preference data on how commuters traveled to work, rather than stated preference data regarding prospective or anticipated behavior.

The data for this analysis originate from the 2007/2008 Washington DC Household Travel Survey. The survey comprises information about free car parking, public transportation benefits, facilities/services for cyclists and pedestrians (such as showers and lockers), and secure bicycle facilities (such as bike parking) at work. A multinomial logistic regression analysis is used to examine the impact of these different types of commuter benefits on mode choice by comparing public transportation users, pedestrians, and cyclists to motorists.

The following section provides a brief overview of the literature on commuter benefits. Then, an empirical analysis investigates the relationship between transportation mode choice for travel to work and commuter benefits for motorists, public transportation users, pedestrians, and cyclists in the Washington, DC region.

About the National Center for Transit Research

www.nctr.usf.edu/

NCTR’s purpose is to make public transportation and alternative forms of transportation, including managed lanes, safe, effective, efficient, desirable, and secure. The goals of NCTR are to: Minimize traffic congestion Maximize mobility options Promote safety and security Improve the environment Enhance community sustainability

Tags: D.C., Journal of Public Transportation, National Center for Transit Research, NCTR, Parking, University of South Florida, USF, Washington

RSS Feed

RSS Feed