THE CITY OF NEW YORK: DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING

Report Dated March 2011

Introduction

New York is famous for its dazzling skyline, iconic bridges, glorious parks, and grand avenues. But our global city possesses two other extraordinary physical assets: our waterfront and waterways. Four of New York’s five boroughs are on islands, and the fifth is a peninsula—and that translates into 520 miles of shoreline bordering ocean, river, inlet, and bay.

New York’s edge is not just expansive, it’s astonishingly diverse. Our waterfront is brawny, home to maritime industries and the largest port on the East Coast. It’s sporty, laced with biking trails and dotted with boat launches. It’s natural, inhabited by hundreds of species of birds and fish. It’s peaceful, with parks that offer places for quiet contemplation as well as active recreation. And it’s historic, encompassing buildings dating to the 1700s and archaeological sites that go back even further.

Above all, our waterfront is constantly changing. After decades of turning our backs on the shoreline—allowing it to devolve into a no-man’s land of rotting piers, parking lots, and abandoned industrial sites—New York made reclamation of the waterfront a priority. In 1992 the Department of City Planning issued the New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, the first time in the history of New York that a long-range vision was offered for the entire shoreline. A bold rethinking of the water’s edge as a place not only for commerce and industry but also for people to live and play, the plan proposed ways to reinvent the shoreline for public access and productive uses. In recent years, we’ve opened parks and greenways on the waterfront, built new housing, restored natural habitat, and fostered all sorts of recreation from kayaking to rollerblading. Today our waterfront has become a destination in and of itself like never before in New York’s history.

But that doesn’t mean it can’t get even better.

Problems remain on the waterfront, including uneven development, crumbling infrastructure, and the contaminated areas known as brownfields. Some neighborhoods are still cut off from the waterfront. In 2008, New York launched a citywide, multi-agency initiative to create a new sustainable blueprint for the shoreline. Called the Waterfront Vision and Enhancement Strategy, this effort has two parts. The first is Vision 2020: New York City’s Comprehensive Waterfront Plan—the plan you are now reading. Crafted with the help of city, state, and federal agencies as well as non-governmental advisory groups and members of the general public, Vision 2020 establishes eight broad goals (see capsule descriptions on the facing page) and offers hundreds of recommendations for the waterfront and waterways for the next decade and beyond.

…

Increase Climate Resistance

New York’s shoreline has been dramatically altered over the centuries. From the moment the Dutch arrived in Nieuw Amsterdam, piers, wharves, docks, and bulkheads have been built. And landmass itself has been added, through the process of fill. While such modifications to the landscape have radically changed the shoreline ecology, they’ve also given rise to the region’s economic engine and enabled more than eight—and soon nine—million people to inhabit the city. New York’s ability to support a large population and substantial employment in a small area is one of its greatest contributions to the environment, resulting in per-capita carbon emissions that are one-third the national average and allowing the preservation of open space and natural resources elsewhere. In recent years substantial improvements to water quality and marine ecology have been made, even as the population of New York has continued to grow.

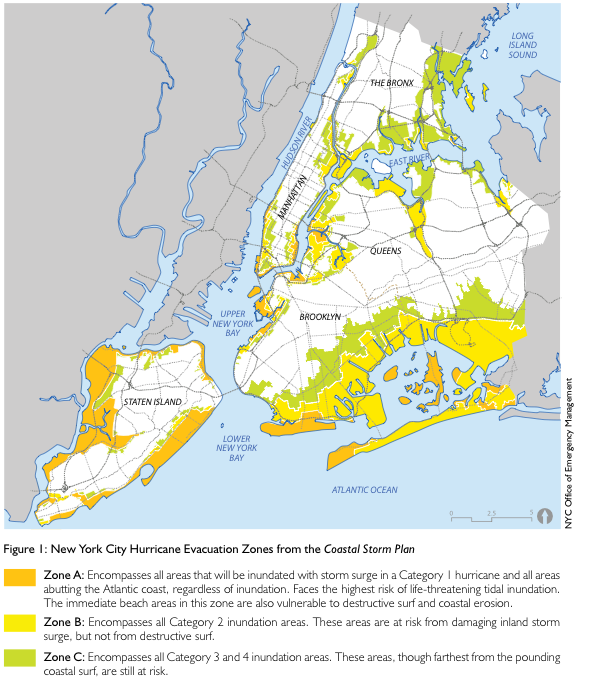

Now human activity is altering the waterfront in a new way. Climate change resulting from global greenhouse-gas emissions is expected to cause sea levels to rise, which will further transform our shoreline. The New York City Panel on Climate Change projects that by the 2050s, sea levels could be 12 inches higher than they are today or, in the event of rapid melting of land-based polar ice, as much as 29 inches higher than today. By the 2080s, increases of up to 23 to 55 inches are projected. And as the sea level rises, the risks from severe storms and flooding that New York has always faced as a coastal city exposed to the ocean are expected to increase, too.

New York is already taking steps to address climate change. The City is working to reduce its contribution to climate change through the PlaNYC goal of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions 30 percent by 2030. Adaptations to our environment to increase the city’s ability to withstand and recover quickly from weather-related events, or its climate resilience, are also being contemplated and made.

Building climate resilience requires recognition of the character of New York City’s coastal areas as well as the risks they face. For instance, most portions of New York stand several feet or more above sea level, and therefore face different challenges from, say, New Orleans or the cities of the Netherlands, substantial portions of which are below sea level. In those cities, flood-waters do not naturally recede after a storm, exacerbating the potential for damage and disruption, as seen with Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. Then, too, New York City’s potential for flooding comes primarily from coastal waters, as opposed to the river flooding that cities such as London must address. For New York City, both temporary inundation from higher sea levels and damage from storm surges must be considered. The impacts of flooding and wave action may make sense to address separately or in combination, depending on circumstances.

Building resilience to coastal storms and flooding anticipated in the future does not lend itself to quick or simple solutions. Strategies that have historically been used to divide water from land will not make sense with climate change and sea level rise. To simply bulkhead the entire waterfront would not adequately address risks, would become increasingly costly, and would have negative ecological consequences for our waterways and coastal areas. To abandon dense coastal neighborhoods would have enormous costs as well. A balanced approach to increasing climate resilience will require case-by-case analysis, drawing on a toolkit of strategies that the public and private sectors can consider and apply to address vulnerabilities. In deciding among a range of practical alternatives, it will be important to consider the costs and benefits of each option, as well as opportunities to address multiple goals. Any strategy must recognize the ecological benefits of wetlands, shallows, and intertidal zones, along with other public priorities such as waterfront access and economic development.

Because certain risks are unavoidable, a resilience strategy should not seek to eliminate all risks. Instead, the city must identify and manage risks; take steps to minimize danger to lives and damage from flooding and storms; and limit disruptions from storm events and the recovery time after such events. Implementing a resilience strategy will require actions not only by government, utilities, and other public entities, but also by private property owners, businesses, and communities. In some instances, more restrictive government regulations may facilitate increased resilience, while in others regulatory or other impediments may need to be modified to allow citizens and government the latitude to implement adaptation strategies.

Download full report (NYC.gov): Vision 2020: New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

About The Department of City Planning

www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/

“The Department of City Planning (DCP) promotes strategic growth, transit-oriented development, and sustainable communities in the City, in part by initiating comprehensive, consensus-based planning and zoning changes for individual neighborhoods and business districts, as well as establishing policies and zoning regulations applicable citywide. It supports the City Planning Commission and each year reviews more than 500 land use applications for actions such as zoning changes and disposition of City property. The Department assists both government agencies and the public by providing policy analysis and technical assistance relating to housing, transportation, community facilities, demography, waterfront and public space.”

Tags: Hurricane Sandy, New York, NY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed