SMART GROWTH AMERICA

Metropolitan Boston is leading the country toward a walkable urban future.

That future is materializing on less than six percent of the metropolitan area’s land —the same six percent that houses 37 percent of the region’s real estate square footage, 40 percent of its population, and 42 percent of employment.

In the Boston metropolitan area, walkable urbanism adds value. On average, all of the product types studied, including office, retail, hotel, rental apartments, and for-sale housing, have higher values per square foot in walkable urban places than in low-density drivable locations. These price premiums of 20 to 134 percent per square foot are strong indicators of pent-up demand for walkable urbanism.

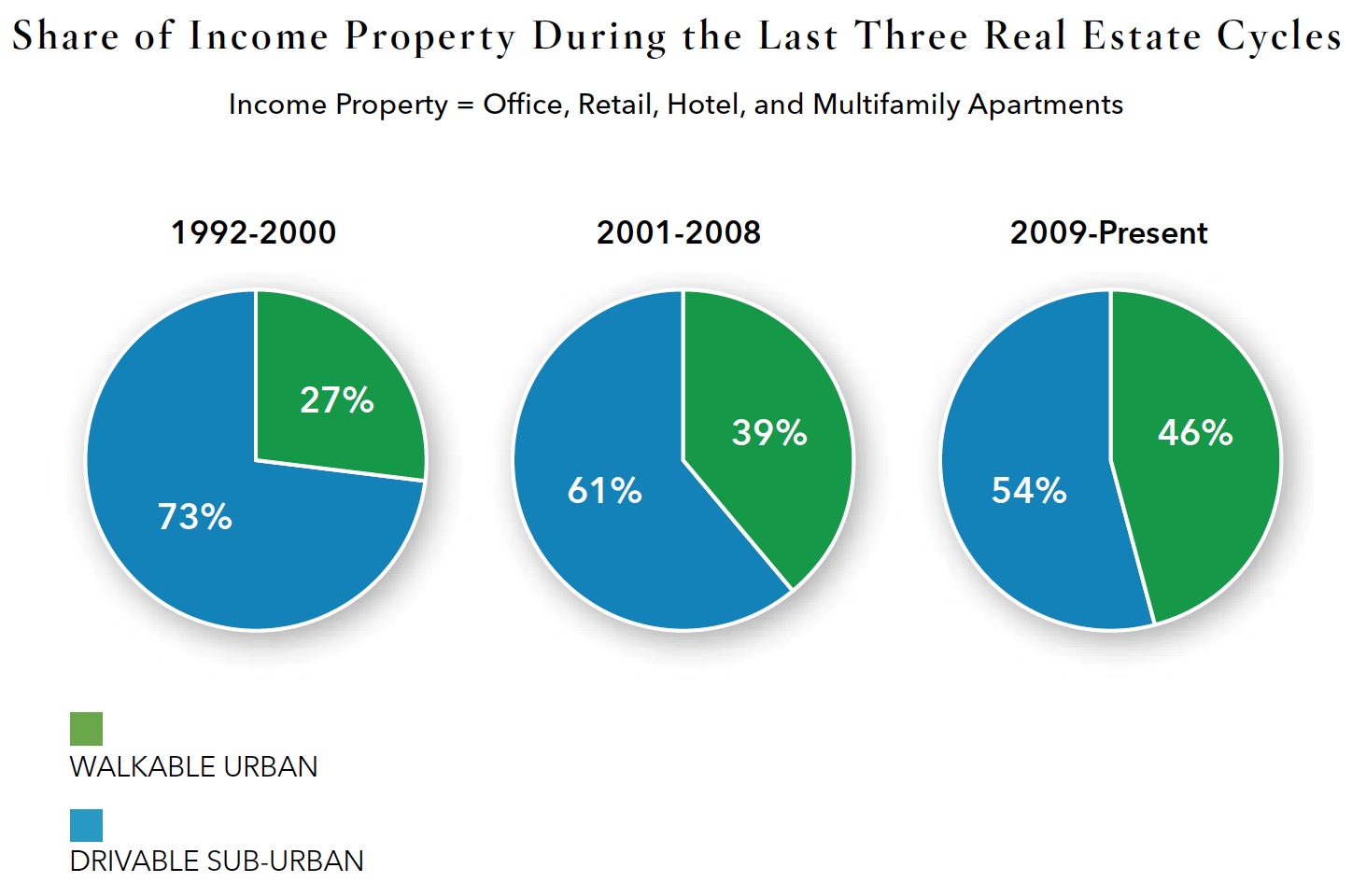

Walkable urban places are now gaining market share over drivable locations for the first time in at least half a century in hotel, office and rental apartment development. This is good news for people moving to those locations, since households in walkable urban places spent less on housing and transportation (43 percent of total household budget) than households in drivable locations (48 percent), primarily due to lower transportation costs.In addition, property tax revenues generated in walkable urban places are substantially higher than in drivable locations on a per acre basis.

Previous research has demonstrated the correlation between walkable urban places and both the education of the metropolitan work force and the GDP per capita. The current research confirms this finding: for example, since 2000, 70 percent of the population growth of young, educated workers has occurred in the walkable urban places of the Boston region.

Despite the strong momentum toward a more walkable urban future for the region, there are challenges and causes for concern. In many walkable urban places, proximity to transit is a major requirement for households and employers.However, increasing congestion in the core transit system and system fragility in the face of extreme events (such as was experienced during the blizzards of 2015) diminish the value of the system and present substantial risks that may deter investors.As a result, public sector investments in MBTA capacity and resiliency are prerequisites for the billions of dollars of private sector capital seeking to flow into walkable urban places over the coming decades.

Public transit, especially rail transit, activates walkable urbanism’s potential for adding real estate value, and as this report demonstrates, that potential is ample. Therefore, policymakers must weigh the costs of funding transit against its power to increase tax revenues.With the right value capture tools in place, the increased value that transit supports could be used to fund at least a portion of the system’s maintenance and future expansion.

We should also be concerned that, given the flow of capital into walkable urban places and the price premiums, the affordability of these places may be diminished. The resulting increased displacement of low-income residents to less accessible suburban locations would likely have substantial negative impacts on social equity, the environment and opportunity. As a result, it is critical to establish policies that will preserve existing affordable housing in walkable urban places and leverage private sector investments to enhance opportunities for disadvantaged families to live in high opportunity/high accessibility places. However, the ultimate solution to high housing and commercial costs is more walkable urban inventory, which will occupy less than 10 percent of the metro area’s landmass. This new inventory will eventually drive down land costs, the primary reason for the price premiums.

Introduction

For decades, real estate practitioners, observers and scholars studying land use have looked through an urban-versus-suburban lens. It is not unlike the classic social science joke about the tipsy guest who drops his keys at the front door as he leaves a party. While searching under a streetlight at the curb, he is asked, “Why aren’t you looking where you lost the keys?” He replies, “This is where the light is.”

We have watched and analyzed the urban/suburban debate where the light was, even if that meant using the wrong approach with the wrong datasets. Our latest research, focused here on Metropolitan Boston, challenges those connected with the built environment (real estate and infrastructure), including developers, investors, regulators, infrastructure providers, social equity advocates, public sector managers, academics and citizens, to rethink the way we manage the 35 percent of our nation’s wealth that is invested in the built environment. This is an important recalibration that affects how we live and work and where we are educated, worship and entertained. To ignore this structural change would be akin to ignoring the impact of the drivable suburbs on the built environment more than a half-century ago.

This new research defines—in an entirely new way— the form and function of all land use in Metropolitan Boston’s 3,119 square miles. This study then ranks performance for all land in the region based on two criteria: economics and social equity. The economic performance metric measures both the real estate valuations, as a proxy for GDP (a GDP measure does not exist below the metropolitan level) and the tax assessment that drives most local government tax revenues.The social equity performance metric measures access to economic opportunity and affordability in terms of both housing and transportation costs.

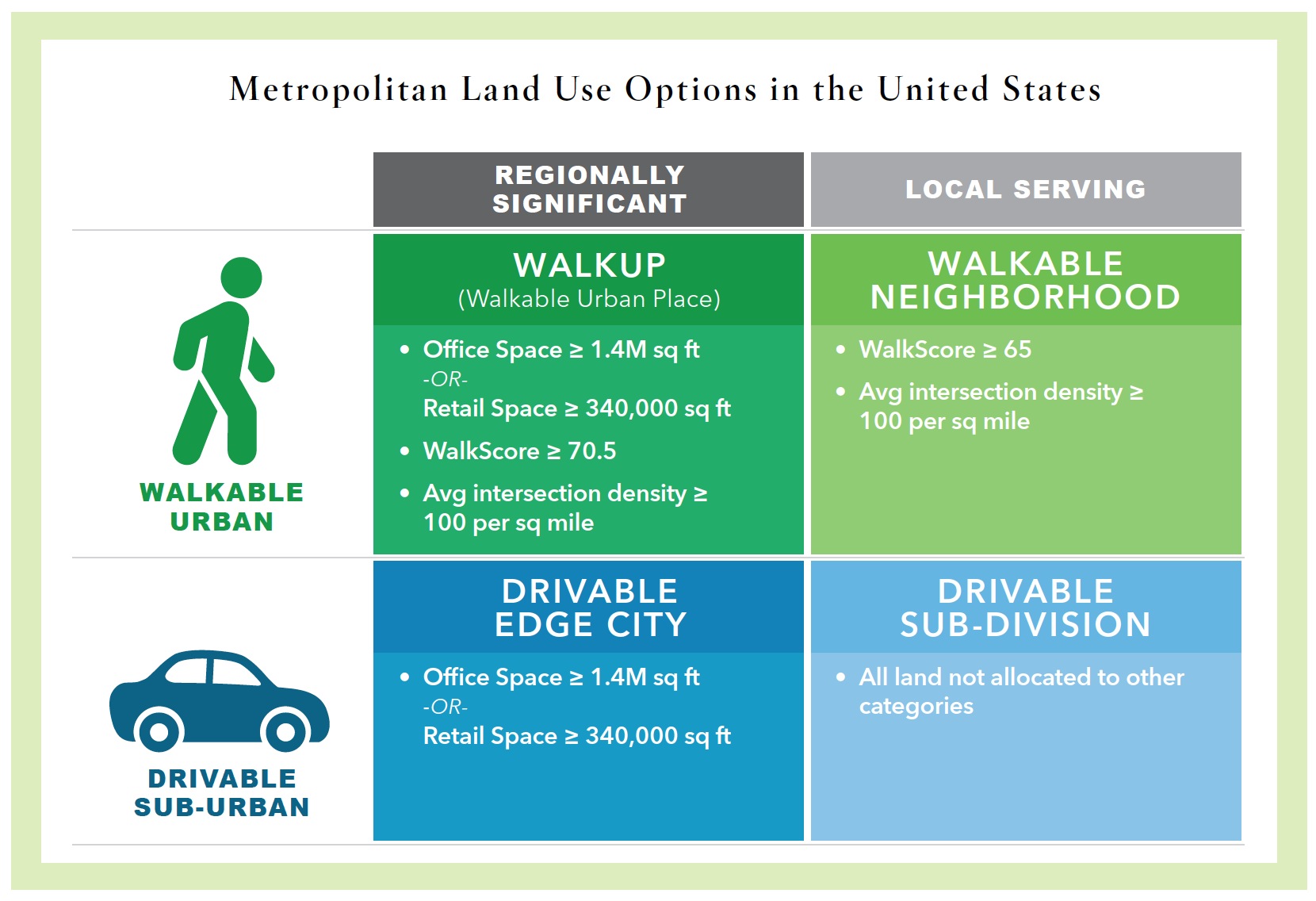

Today, there are two broad forms of metropolitan development:

- Drivable Sub-urban: This development form has the lowest development density in metropolitan history.It features stand-alone real estate products, tends to be socially and racially segregated, and relies upon cars and trucks as the only viable form of transportation.

- Walkable Urban: This form of development has much higher density, has multiple real estate products (housing, office, retail, etc.) close to one another, employs multiple modes of transportation that get people and goods to the place and once there, is walkable.

Each form is found in both cities and suburbs.In the case of Metropolitan Boston, drivable sub-urban development can be found within Boston, in neighborhoods such as West Roxbury and Hyde Park, the many subdivisions throughout the suburbs.Likewise, Boston’s Back Bay takes a walkable urban form, as does the newly opened Assembly Row, a $1.3 billion transit-oriented mixed-use development in a once gritty, former industrial part of the city of Somerville.Both drivable sub-urban and walkable urban forms of development have market support and appeal.

Drivable sub-urban has been the dominant approach to real estate development for over 60 years.Today, that is reversing; the pendulum is swinging back to walkable urban development.Market demand for drivable sub-urban development, which became overbuilt and was a major cause of the mortgage meltdown that triggered the Great Recession, appears to be on the wane in the Boston metropolitan area.Meanwhile, there is such pent-up demand for walkable urban development—as demonstrated by rental and sales price per square foot premiums—it could take a generation of new construction to satisfy the demand for walkable urban development.

Meeting this demand for new development in walkable urban areas will be a boon to the economy.Much like drivable sub-urban development benefited selected jurisdictions in the second half of the 20th century, this shift back towards walkable urbanism provides the opportunity that many urban neighborhoods, long suffering from disinvestment, have been waiting for.It will also put a foundation under the Boston regional economy and boost local government tax revenues, much like drivable sub-urban development benefited the economy and selected jurisdictions in the second half of the 20th century.

Walkable urban development calls for dramatically different approaches than drivable sub-urban to urban design and planning, regulation, financing and construction.It also requires the introduction of a new industry: place management.This new field develops the strategy and provides the day-to-day management for walkable urban places, creating a distinctive “could only be here” place in which investors and residents invest for the long term.

The comparisons between different land use forms will help direct private sector investment decisions, public sector infrastructure investments, and public policy and household decisions about where to live, work and play.In addition, place management organizations could use the metrics developed in this report to assess year-over-year performance and progress made in achieving strategic objectives.Finally, the research can assist in setting urban policy of the Commonwealth, especially for economic development, housing and transportation.

Download full version (PDF) – The WalkUP Wake-Up Call: Boston

About Smart Growth America

www.smartgrowthamerica.org

Smart Growth America advocates for people who want to live and work in great neighborhoods. We believe smart growth solutions support thriving businesses and jobs, provide more options for how people get around and make it more affordable to live near work and the grocery store. Our coalition works with communities to fight sprawl and save money. We are making America’s neighborhoods great together.

Tags: Boston, MA, Massachusetts, urban, Urbanism

RSS Feed

RSS Feed