MassINC

Executive Summary

Gateway Cities can accommodate thousands of new housing units and thousands of new jobs on the vacant and underutilized land surrounding their commuter rail stations. This walkable, mixed-use urban land offers an ideal setting for transit-oriented development (TOD) to take hold.

Currently, Gateway City commuter rail stations get minimal ridership from downtown neighborhoods and few developers seek out this land for TOD. But changing economic forces may provide market-building opportunities that we should not overlook—funneling future development into transit-connected Gateway Cities could generate more inclusive and economically productive growth, reduce road congestion and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, increase housing supply, conserve open space, and improve quality of life in communities throughout the Commonwealth.

At this moment of profound demographic, economic, and technological change, it is difficult to quantify precisely this host of potential benefits. However, aggressively pursuing the promise of Gateway City TOD does not require a billion-dollar upfront bet. The transit network—along with the urban fabric to facilitate this form of development—already exists.

Governor Baker recently named an 18-member commission to examine the state’s transportation assets and future mobility needs, including re-evaluating the role commuter rail plays before MassDOT issues the next long-term operating contract in 2022. While transportation leaders plan ahead, tools to spearhead redevelopment in Gateway Cities are in flux, with the Legislature considering end-of-session housing and economic development bills. At this important juncture, it is crucial to gain a more complete understanding of the opportunity Gateway City TOD presents.

To provide this information, MassINC assembled an interdisciplinary research team to construct detailed real estate and transportation models for four Gateway Cities (Fitchburg, Lynn, Springfield, and Worcester) with widely varying market contexts. Using parameters derived from these models, the team then extrapolated to the full set of 13 Gateway Cities with current or planned commuter rail service (see Table ES-1).

Our analysis yields order-of-magnitude estimates to answer the threshold question: How much employment and population growth, increased transit ridership, and GHG emission reductions are possible, if Massachusetts were to realize the full potential of Gateway City TOD?

This executive summary presents five key findings from our research, and then briefly describes how, leveraging our models, state and local leaders can proceed apace with steps to nurture and test the market for Gateway City TOD and make measured progress toward its full potential, as rising demand warrants additional investment in station area development and transit service improvements.

1. Changing economic forces provide fertile ground for Gateway City Transit-Oriented Development (TOD).

To dispassionately weigh order-of-magnitude estimates for Gateway City TOD at its full potential, leaders must first assess the economic case, because market forces ultimately dictate land use, as well as the broader social and environmental benefits associated with transit and compact urban development.

Currently, real estate economics do not reflect demand for Gateway City TOD: station area rents are simply too low to support substantial rehab or ground-up new development. However, this could change markedly as the innovation economy continues to expand.

Innovative regional economies are driven by dense clusters of business activity, where workers in related industries can exchange knowledge and create new products and services. Economists call the force that fuels this phenomenon “agglomeration.” Because access to a large pool of workers with specialized skills is central to the development of agglomeration economies, the more transportation systems expand the potential pool of workers, the more competitive a region will become.

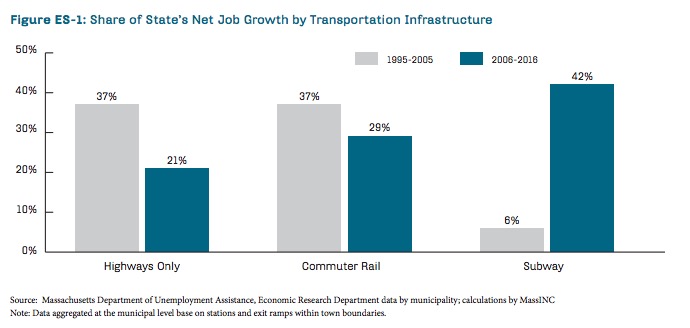

In recent years, Greater Boston has seen the impact of rising returns to agglomeration with employer after employer migrating from locations along highway exit ramps to Boston’s urban core, where robust transit service provides them with the widest possible labor market draw. Communities with high-frequency subway service accounted for 42 percent of all net job growth in Massachusetts between 2006 and 2016; this same set of communities generated just 6 percent of the state’s net job growth during the previous 10-year period (Figure ES-1).

With the economy increasingly driven by agglomeration, and space to expand housing and commercial development in Boston increasingly scarce, a strengthening market for Gateway City TOD seems likely. If mixed-use TOD in Gateway Cities becomes a catalyst for improved regional mobility (with far more locations for both living and working up and down commuter rail corridors that are served by faster and more frequent trains), it could reshape the contours of the Commonwealth’s economic geography and increase the state’s overall competitiveness.

A growing body of evidence suggests a large center city connected to smaller cities allows regions to maximize benefits from agglomeration, while minimizing congestion and other inefficiencies that come with size. This only occurs, however, when these smaller cities develop functional relationships with the large core to “borrow size” (i.e., gain the productivity benefits such as skilled labor and connections to global cities that come with scale). Without these functional relationships, smaller cities tend to fall in the so-called agglomeration shadow, where the competitive advantage firms gain in the central city makes it difficult for others to compete nearby.

At present, it is quite clear that an agglomeration shadow hangs over Gateway Cities and their regional economies. TOD coupled with improved transit service could move markets toward the borrowed size pattern, with larger and larger flows of workers moving quickly through congested metropolitan space to Gateway City economic centers tied to Boston’s research and development activity, expert service providers, and global trade connections.

2. Gateway City station areas can accommodate a substantial amount of additional development.

If the pro-Gateway City TOD economic forces described above take shape, our models suggest the station areas in these cities have significant capacity to absorb more development, respecting their current scale and character. This additional capacity comes in three forms: infill on currently vacant sites; higher occupancy of underutilized buildings; and redevelopment on parcels where existing structures are significantly less dense than those nearby.

Combined, these three forms of capacity present an opportunity to expand the volume of space in these downtown station areas by a range of 56 percent in Fitchburg to 225 percent in Lynn. Together, the 13 Gateway Cities with current or planned commuter rail service have an estimated 116 million square feet of additional development potential within a half-mile radius of their stations.

At “optimal buildout”—the term we use hereafter to describe maximum development at the current scale and full utilization of this real estate with a one-to-one mix of jobs and residents—these Gateway City TOD areas could house approximately 230,000 jobs and 230,000 residents. This represents a 157 percent increase over the current number of people working in these areas (139,825 additional jobs) and a 155 percent increase over the current number of residents living in them (140,358 additional residents).

To put this magnitude of potential development capacity into perspective, the job growth figure is equivalent to 70 percent of all net new jobs in Massachusetts since 2001, and the additional housing estimate is enough to accommodate over one-quarter of the projected population growth for Massachusetts statewide through 2035.

3. Gateway City TOD will produce a heavy stream of new riders; the commuter rail system has capacity to carry all of these additional passengers with limited marginal cost.

With conservative assumptions, our ridership model shows Gateway City Transit-Oriented Development has the potential to generate large increases in rail passengers. At optimal buildout, daily boarding in Worcester increases by nearly 200 percent and Fitchburg’s ridership grows by 280 percent. Consistent with the exceptional development opportunity along the city’s waterfront, Lynn posts exponential ridership gains: at optimal buildout, the station would serve nearly 7,000 daily riders, ten times current levels.

Combined, optimal buildout in the 13 Gateway Cities produces approximately 25,000 new daily passengers. At current fares, this level of ridership generates more than $81 million in additional revenue annually for the MBTA.

Currently, most of the coaches that the MBTA owns are in use during peak service periods and most seats are occupied during a portion of these high-volume trips (based on the corridors we studied). But this is by design, as the agency maintains a fleet of coaches to accommodate the run with the most passengers on each line. With minor additions to capacity and service, such as replacing single-level coaches with bi-level coaches, the system can serve the estimated peak period TOD ridership with limited marginal cost.

Service enhancements, including more frequent headways (i.e., elapsed time between trains) and reductions in travel time, could generate even more ridership from Gateway Cities and other stops along these lines. This would undoubtedly require sizeable public investment. However, with Gateway City stations performing at their full potential, the cost-benefit proposition might balance out, justifying service enhancements that will improve mobility for all communities in these commuter rail corridors.

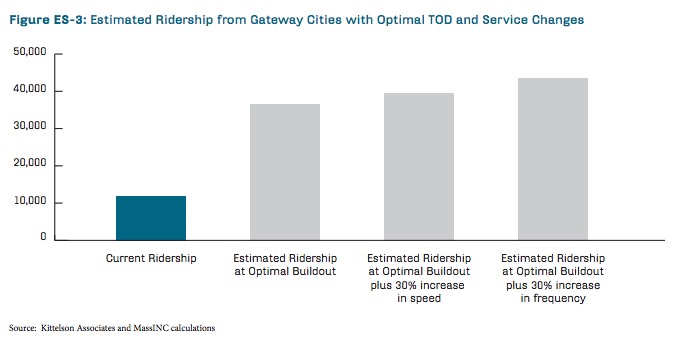

For instance, we estimate that without any additional development in Gateway Cities, a 30 percent increase in frequency leads to 4,500 additional daily boardings from these 13 stations; at optimal TOD buildout, a 30 percent increase in frequency generates over 7,000 new trips (Figure ES-3).

About MassINC

massinc.org

MassINC was built around the conviction that better outcomes would be achieved if policy makers and opinion leaders were armed with credible data and analysis about key issues surrounding quality of life in Massachusetts. Unbiased, fact-based analysis have always been cornerstones of MassINC’s work and have made us the organization of record for policy analysis and civic engagement.

Tags: Boston, MA, Massachusetts, MassINC, TOD, Transit-Oriented Development

RSS Feed

RSS Feed