MANHATTAN INSTITUTE

By Nicole Gelinas, Senior Fellow

Executive Summary

Performance at the Metropolitan Transportation Authority continues to slip, with only 65% of subway trains running on time during the first five months of 2017, down from 86% five years ago. Trains are also failing more often: every 115,527 miles, down from 170,206, or a 32% decline, from half a decade ago. In April 2012, 21,944 trains suffered delays. By April 2017, the figure had risen to 58,651. This year, riders have put increasing pressure on the governor, who names a plurality of the MTA’s board members, to improve the situation.

Government officials, including the governor, as well as outside policymakers, have blamed a lack of funding. Yet a historical review of the MTA’s finances reveals that the authority is taking in a record amount of revenue. The MTA’s revenues have more than kept up with inflation and with service enhancements to keep up with ridership growth.

Even as the MTA’s revenues have increased over the decades, its costs to operate subways, buses, and commuter rails have outpaced these gains. Over little more than a decade, the MTA’s costs, excluding debt service, have outpaced inflation by 50%. This fundamental imbalance prevents the state from providing New Yorkers with the transit service that a growing city demands. Below are answers to some questions about the transportation authority’s finances.

Q: How does New York fund the MTA?

A: Mostly from fares and tolls but increasingly from taxes.

Until 1980, the MTA funded itself through passenger fares and tolls as well as through inconsistent annual subsidies made by the state and city. This method of funding left the MTA with vast capital shortfalls for infrastructure investment. Subway assets deteriorated significantly between the 1960s—when the state-created authority had to take over the subways from the failing city government—and the early 1980s.

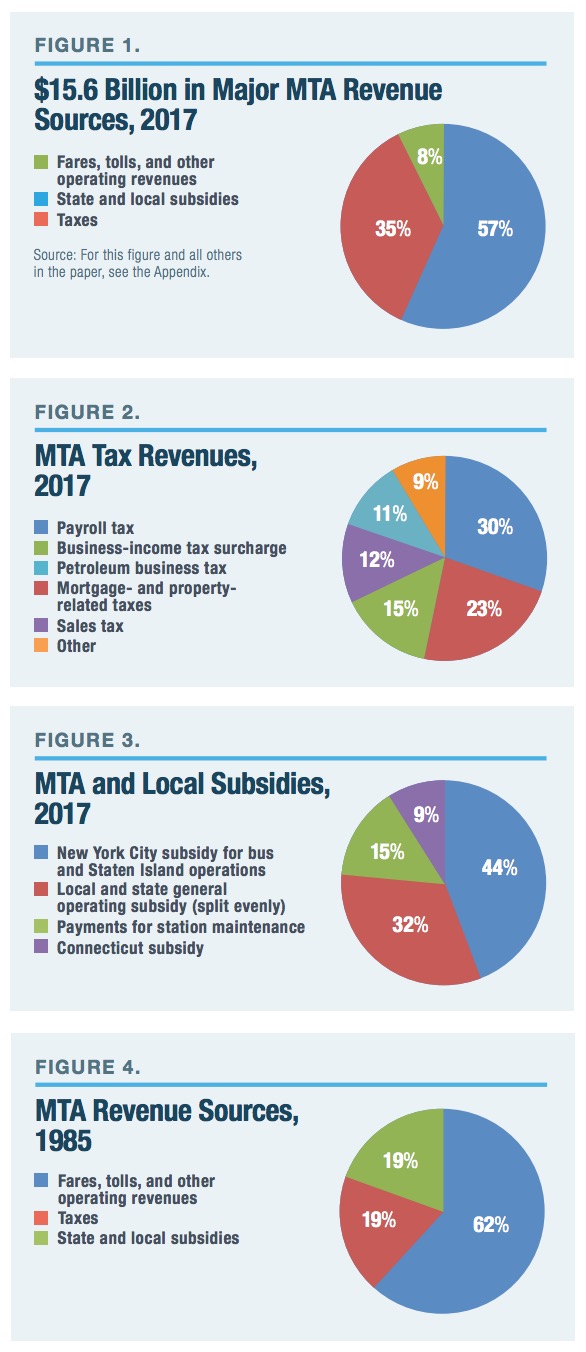

In 1981, MTA chairman Richard Ravitch, appointed by Governor Hugh Carey, convinced the state legislature that it needed to enact a series of permanent annual taxes to sustain the MTA. These tax revenues were to supplement the fares and ad-hoc state and local subsidies and allow the MTA to reinvest in its infrastructure, which it began to do a year later under the first fiveyear capital plan, a strategy that continues to this day. The MTA now receives a significant amount of revenue from fares, taxes, and subsidies. (Figure 1)

Q: Have the MTA’s revenues kept up with inflation?

A: They have exceeded inflation significantly, thanks to increasing fares, taxes, and subsidies.

The MTA’s sources of tax revenues have grown in real terms since 1981. Back then, the state legislature expected that the taxes it had enacted would bring in $2.2 billion (all numbers are in today’s dollars) when fully phased in.5 Today, these taxes, as well as new legislative packages over the decades, bring in $5.5 billion.

These taxes are diverse, although all derive from the 12 downstate New York counties, including New York City, where the MTA serves its riders. The MTA now receives money each year from a payroll tax levied on wage, salary, and bonus earners ($1.7 billion), a charge on mortgages and other property-related transactions ($1.2 billion), a surcharge on business-income taxes ($817 million), a portion of the downstate sales tax ($684 million), a tax on petroleum businesses ($607 million), and several smaller tax sources ($472 million). (Figure 2)

New York’s state and local governments, as well as the state of Connecticut, also now provide consistent, rather than ad-hoc, subsidies from their own general budgets. Governments fund these subsidies out of their taxpayers’ general revenue base. (Figure 3)

The MTA’s tax and subsidy revenues have been a significant part of the transportation authority’s budget since the state and city fully implemented them in the mid- 1980s. In 1985, for example, the MTA derived 38% of its operating revenues from taxes and subsidies rather than from fares and tolls (Figure 4); today, that figure is 43%.

The share of MTA funds that the authority derives from taxes and other subsidies has fluctuated but has remained stable over the past half-decade, at well above 40%. (Figure 5)

That percentage has remained stable only because nearly all the MTA’s varied sources of revenues—fares, tolls, and taxes—have grown in real terms (that is, after inflation) throughout the modern era. The MTA now takes in 72% more annually in fare revenue compared with 1985, for example, nearly keeping up with growth in ridership. But tax revenues have nearly tripled in real terms over three decades. State and local subsidies have lagged inflation, but higher tax revenues more than make up for this lag. (Figure 6)

Tax revenues have grown because the legislature has approved new taxes, to be sure: most recently, in 2009, lawmakers enacted the tax on downstate payrolls as well as several smaller taxes. But tax revenues have also grown naturally with the economy, particularly over the past decade. (Figure 7)

Q: If revenues have more than kept up with inflation, why does the MTA face a funding crisis today?

A: Operating costs have outstripped revenue. Even as revenues have soared, operating costs have soared as well.

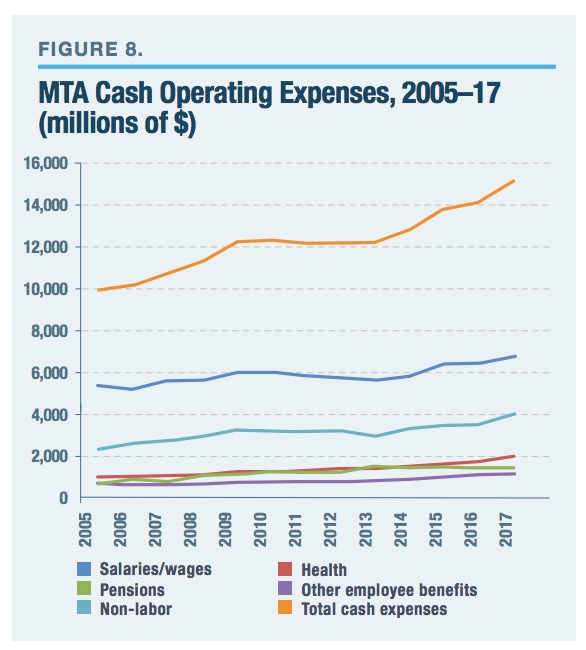

In the past 12 years, the MTA’s cash operating expenses, not including annual debt service, have increased 53% greater than inflation. (Figure 8)

Q: Is the MTA spending more to provide more and better service?

A: Not significantly.

MTA ridership has soared over the past three decades. Subway ridership—which constitutes 65% of MTA operations—is up 86% since 1985. But the MTA’s high expenditures are not a result of better service in light of higher ridership. To the contrary, the MTA has not added subway trains—or the employees to operate them—commensurate with this ridership growth. Indeed, it didn’t have to match ridership growth with equivalent service growth. Up until the past decade, the subway system had plenty of extra capacity, with evening, weekend, and outer-borough trains running at well above peak demand. The number of weekday subway trains is up only 24% in the past three decades. Moreover, the number of employees who work for the MTA’s subway and bus division—New York City Transit—is down 8%, compared with three decades ago, when managers oversaw a surge in hiring after the first infusion of new revenues to clean cars of graffiti and to rebuild and maintain tracks. (Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11)

Q. If the number of employees has declined, what accounts for the MTA’s growing costs?

Q. If the number of employees has declined, what accounts for the MTA’s growing costs?

A. Employee benefits.

Pensions and health care are the main drivers of the transportation authority’s increased costs. Consider that in 1985, retirement and health benefits for New York City Transit personnel cost $1.2 billion in today’s dollars. Today, they cost nearly $3.1 billion annually. At the MTA as a whole, in 2005, such costs constituted 23% of employee spending, costing $2.5 billion in current dollars. Today, they constitute 30%, costing $4.5 billion. This increase in benefits costs alone consumes all the additional revenue that the MTA takes in annually from the payroll tax that the state legislature implemented in 2009. (Figure 12, Figure 13)

Q: What other MTA costs have grown significantly?

A: Debt—and the cost of servicing that debt.

Because the MTA spends so much on its operational costs, it takes on debt to pay for a substantial portion of its capital investments; nearly $9.9 billion over the current five-year period alone. In the early 1980s, the MTA had virtually no debt. Today, it owes nearly $40 billion. (Figure 14)

The MTA must spend increasing amounts of annual revenue to service this debt. To be sure, the MTA has repeatedly refinanced its debt to take advantage of record-low interest rates, helping to curtail growth in costs. But the authority has grown accustomed to low borrowing costs and has correspondingly adjusted by borrowing even more money.

Taking on debt to invest in long-lived assets is a financially sound practice. However, the MTA’s legacy of debt from past capital-investment programs consumes today’s revenues even as some of the infrastructure funded with that debt has expended its useful life. This imbalance leaves less money for the authority to invest in the future. (Figure 15)

Download full version (PDF): The MTA’s Escalating Cost Crisis

About the Manhattan Institute

www.manhattan-institute.org

The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research is a leading voice of free-market ideas, shaping political culture since our founding in 1977. Ideas that have changed the United States and its urban areas for the better—welfare reform, tort reform, proactive policing, and supply-side tax policies, among others—are the heart of MI’s legacy. While continuing with what is tried and true, we are constantly developing new ways of advancing our message in the battle of ideas.

Tags: Manhattan Institute, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, MTA, New York City, Nicole Gelinas, NYC, Subway

RSS Feed

RSS Feed