INSTITUTE FOR TRANSPORTATION AND DEVELOPMENT POLICY & EMBARQ

Introduction

From the 1940s to the 1960s, U.S. cities lost population and economic investment to suburban locations. To compete, many cities built urban highways, hoping to offer motorists the same amenities they enjoyed in the suburbs. Whatever their benefits, these highways often had adverse impacts on urban communities.

In the United States, federal policy and funding spurred investment in urban highways. The U.S. Highway Act of 1956 set the goal of 40,000 miles of interstate highways by 1970, with ninety percent of the funding coming from the federal government. Fifty percent federal funding was the norm for other transportation projects. By 1960, 10,000 new miles of interstate highways were built and

by 1965, 20,000 miles were completed. While most of the investment occurred outside cities, about twenty percent of the funds went into urban settings.

In 1961, Jane Jacobs challenged urban renewal and urban highways in her seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs commented on the effects of highways on communities, stating, “expressways eviscerate cities.” For the first time, the unintended consequences of urban highways, such as displaced communities, environmental degradation, land use impacts, and the severing of communities, were highlighted. Jacobs went on to successfully fight urban highways in New York City and Toronto, and helped spur the formation of some of the most active community-based organizations in the U.S.

This urban activism had, by the late 1970s and early 1980s, made it nearly impossible to build an urban highway or raze a low-income neighborhood in the United States. New environmental review procedures were put in place to protect communities and parks from the effects of highways. However, the U.S. continued to build and widen highways, moving the construction of virtually all of them to suburban or inter-urban locations. By 1975, the goal of 40,000 miles of new interstate highways had been achieved.

…

Case Study

Park East Freeway, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Background

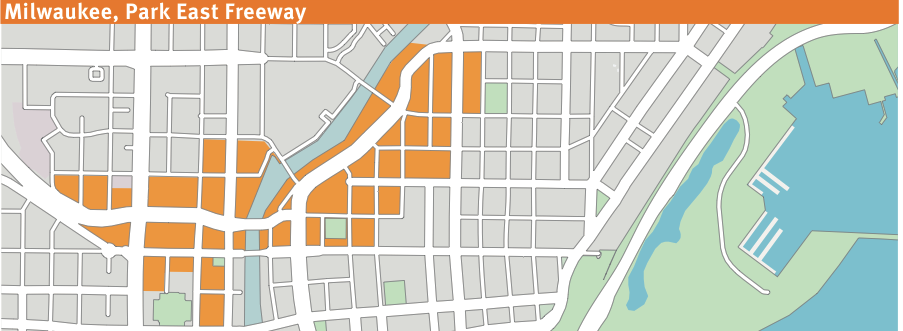

In the late 1940s and 1950s, the Milwaukee city government introduced plans for the construction of a ring of freeways around the downtown. The Park East Freeway was to connect to I-794, a 3.5-mile freeway linking Lake Michigan to the southern suburbs, and, in combination with the Park West Freeway, would create an east-west regional expressway. The project began in 1971 and was halted in 1972 due to community opposition, and then later abandoned completely, due to rising construction costs and opposition. The incomplete freeway was underused and the land around it, previously cleared for further highway construction, sat vacant for years.

In the early 1990s, the state of Wisconsin finally removed the transportation corridor designation on the cleared land that had prevented it from being developed, and the vacant area was redeveloped into the lively mixed- use development known as East Pointe. The success of its revitalization inspired Mayor John Norquist to remove the under-utilized freeway for further redevelopment and revitalization. Demolition of the Park East Freeway began in 2002 and was completed by 2003.

Today, the area that once housed the Park East Freeway is a neighborhood of shops, apartments, and townhouses, on a traditional street grid. The freeway removal not only helped reduce congestion in the area but helped stimulate development.

About the project

The freeway was a response to the city’s concern about its economic competitiveness and its ability to easily move goods from Milwaukee to major hubs like Chicago. To solve that problem, Milwaukee developed the freeway network that included the Park East Freeway. Property acquisition began in 1965, resulting in the demolition of hundreds of houses and scores of businesses.

By 1971, the first section of the freeway was open and around that same time, local opposition grew because of the highway’s detrimental effect on the city, including the pending severance by the highway of Juneau Park from Lake Michigan and the polluting of the park. Elected officials soon supported the opposition and the project was halted. What remained was a one-mile freeway spur that extended from I-43 in the east, near the waterfront, into downtown Milwaukee. The freeway separated the north side of the city from the downtown area with only three exits as well as interrupting the street grid network. Further construction of the freeway was finally terminated in 1972, when Mayor Henry Maier vetoed any additional funds to the project. (Preservation Institute, Milwaukee, Wisconsin).

Read full report (PDF) here: THE LIFE AND DEATH OF URBAN HIGHWAYS

About The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy

www.itdp.org

“The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy works with cities worldwide to bring about transport solutions that cut greenhouse gas emissions, reduce poverty, and improve the quality of urban life. Cities throughout the world, primarily in developing countries, engage ITDP to provide technical advice on improving their transport systems. ITDP uses its know-how to influence policy and raise awareness globally of the role sustainable transport plays in tackling green house gas emissions, poverty and social inequality. This combination of pragmatic delivery with influencing policy and public attitudes defines our approach. Most recently, ITDP has been instrumental in designing and building the best bus rapid transit systems in the world.”

About EMBARQ

www.embarq.org

“EMBARQ’s goal is simple: make cities around the world better places to live. By focusing on transport, which affects everything from prosperity to pollution, EMBARQ’s work yields social environmental, and economic benefits.”

Tags: EMBARQ, The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, The Life and Death of Urban Highways

RSS Feed

RSS Feed