CNA CORPORATION

Executive Summary

To determine how Texas could be affected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Clean Power Plan (CPP), we applied CNA’s Electricity-Water-Climate power sector model to evaluate the potential impacts. We find that under the CPP, the state will save water and reduce levels of conventional air pollutants. In addition, the state will be able to meet the policy’s targets with modest incremental effort even though electricity demand is expected to increase by 25 percent.

We summarize our main findings:

1. Under the CPP, water consumption by the Texas power sector could be cut by more than 20 percent compared with water consumed in 2012. This is about 88,000 acre-feet per year.

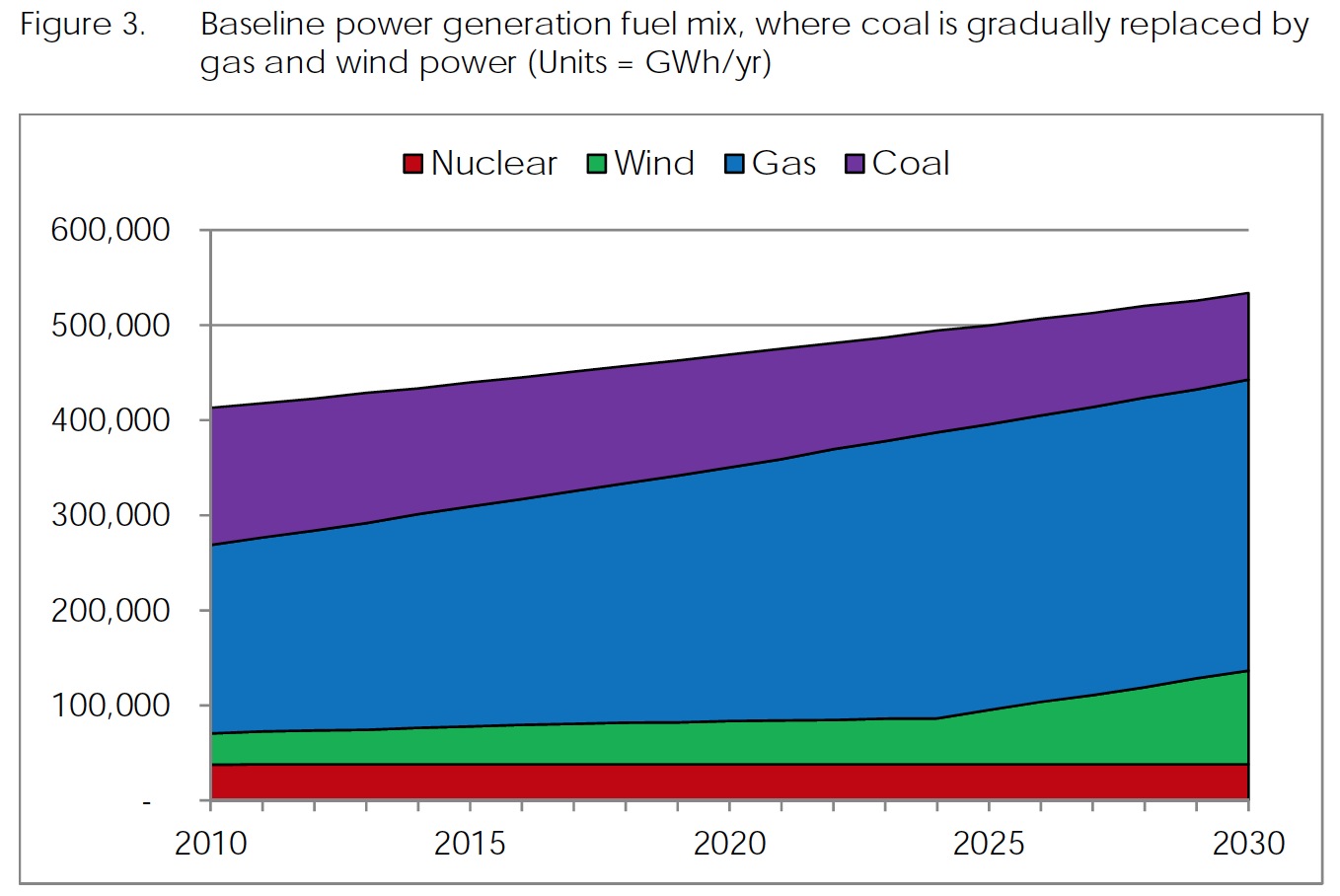

2. The Texas power sector is already moving to cut the carbon dioxide (CO2) intensity of its economy—the objective of the CPP—by shifting away from coal and toward natural gas and wind power.

3. The demand-side energy efficiency gains proposed by EPA would reduce the need for new power generating capacity in Texas. As a result, Texas would avoid increased water use and would significantly reduce conventional air pollution and CO2 emissions.

4. Under the CPP, the cost per unit of electricity produced would increase by 5 percent, but total system costs would decrease by 2 percent.

Background

Drought in Texas

Texas is periodically subject to severe drought. In 2011, the state experienced the worst single-year drought in its recorded history. [1]. Demand for electricity was at an all-time high because of the heat, and the water needed to cool the state’s coal, nuclear, and gas power plants was in short supply. In some places, water levels had dropped below intake pipes; in others, the available water was too hot to provide effective cooling. Texans were warned that rolling blackouts were possible, as power plants that could not be properly cooled would have to shut down [2].

The drought has become less severe since then, but as of August 25, 2014, 59 percent of the state was still under moderate to extreme drought [3]. Reservoirs were about two-thirds full for that time of year, about 20 percentage points below the long-term median [4].

With high population and economic growth, the impact of water stress on the economy is a high priority for the state. The Texas Water Development Board believes that water resources are insufficient to meet projected needs during a drought [5]. In 2005, the largest source of water withdrawals in Texas was for cooling thermoelectric power generation. At 10.9 million acre-feet (ac-ft)1 per year, this use accounted for about 40 percent of total freshwater withdrawals [6]. The power sector’s dependence on water is a source of vulnerability [7].

As Texas grapples with this problem, decision-makers in the state must also consider a new federal policy, one which is aimed at producing a major shift in how electricity is produced in the United States. A key concern for Texas is how the policy will affect water use in the power sector. This report is intended to address that question.

The Clean Power Plan (CPP)

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the Clean Power Plan (CPP) on June 2, 2014 [8].2 Under the plan, the Obama Administration hopes to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the power sector by 30 percent across the country relative to CO2 emission levels in 2005. The CPP defines state-specific CO2 intensity rates—i.e., the number of pounds of CO2 that can be emitted per megawatthour (MWh) of power produced. This rate is determined by dividing total CO2 emissions from the power sector in a given state by total power generation in that state (excluding most of the nuclear power but including renewables) plus demand-side energy efficiency gains. All CO2 emissions from the power sector are under a single state bubble; EPA is not proposing limits for individual power plants, as it does under other rules for conventional air pollutants. EPA’s use of CO2 intensity rates is intended to provide flexibility to state regulatory agencies. In addition, by including demand-side energy efficiency as part of the equation to reduce CO2 emissions, EPA is attempting to provide further flexibility to regulators and to incentivize energy efficiency (EE) programs [10]. EE programs tend to be a low-cost approach to reducing emissions.

EPA specifies two intensity rates: (1) the final rate, a single-year rate that must be achieved by 2029 and (2) the interim rate, which is the average rate between 2020, when the CPP is to come into force, and 2029, the last year of the plan. The rates for each state are determined by EPA analysis [10].

EPA outlines four “building blocks” that states can use to achieve interim and final intensity rates. We list them below:

1. Reduce the CO2 intensity of generation at individual coal-fired power plants through efficiency improvements;

2. Switch generation from coal-fired power plants to natural gas combined cycle plants (NGCC);

3. Employ zero-emission renewable energy and some nuclear power;3 and

4. Reduce emissions by cutting growth in power demand through the use of demand-side energy efficiency. [10]

About CNA Corporation

www.cna.org

CNA Corporation’s objective, empirical research and analysis helps decision makers develop sound policies, make better-informed decisions, and manage programs more effectively. We take a multi-disciplinary, field-based “real world” approach to our work, and provide public-sector organizations with the tools they need to tackle the complex challenges of making government more efficient and keeping our country safe and strong.

Tags: Clean Power Plan, CNA, CNA Corporation, CPP, Environmental Protection Agency, EPA, Texas, TX

RSS Feed

RSS Feed