UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

BROWN UNIVERSITY

Written by Marco Gonzalez-Navarro, University of Toronto, & Matthew A. Turner, Brown University

Abstract: We investigate the relationship between the extent of a city’s subway network, its population and its spatial configuration. To accomplish this investigation, for the 632 largest cities in the world we construct panel data describing population, measures of centralization calculated from lights at night data, and the extent of each of the 138 subway systems in these cities. These data indicate that large cities are more likely to have subways but that subways have an economically insignificant effect on urban population growth. Our data also indicate that subways cause cities to decentralize, although the effect is smaller than previously documented effects of highways on decentralization. For a subset of subway cities we observe panel data describing subway and bus ridership. For those cities we find that a 10% increase in subway extent causes about a 6% increase in subway ridership and has no effect on bus ridership

Introduction

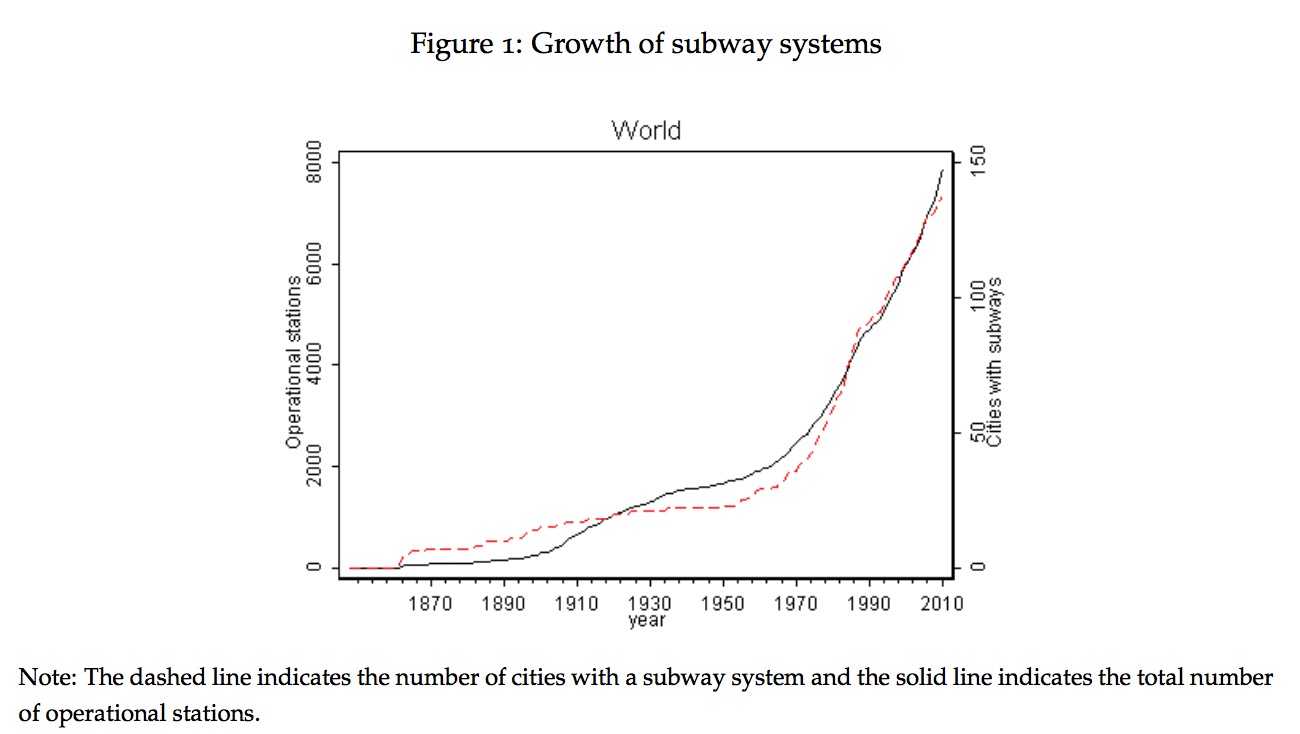

We investigate the relationship between the extent of a city’s subway network and its population, transit ridership and spatial configuration. To accomplish this investigation, for the 632 largest cities in the world we construct panel data describing population, total light, measures of centralization calculated from lights at night data, and the extent of each of the 138 subway systems in these cities. For a subset of these subway cities we also assemble panel data describing bus and subway ridership.

These data suggest the following conclusions. First, while large cities are more likely to have subways, subways have a precisely estimated near zero effect on urban population growth. Second, subways cause cities to decentralize, although this effect appears to be small relative to the decentralization caused by radial highways. Third, a 10% increase in subway extent leads to about a 6% increase in subway ridership and does not affect bus ridership. A back of the envelope calculation suggests that only a small fraction of ridership increases can be accounted for by decentralized commuters. Together with the fact that little new ridership can be attributed to population growth, this suggests that most new ridership derives from an increase in non-commute subway trips.

Subway construction and expansion projects range from merely expensive to truly breathtaking. Among the 16 subway systems examined by Baum-Snow and Kahn (2005), construction costs range from about 25m to 550m usd2005 per km. On the basis of the mid-point of this range, 287m per km, construction costs for the current stock are about 3 trillion dollars. These costs are high enough that subway projects generally require large subsidies. To justify these subsidies, proponents often assert the ability of a subway system to encourage urban growth.1 Our data allow the first estimates of the relationship between subways and urban growth. That subways appear to have almost zero effect on urban growth suggests that the evaluation of prospective subway projects should rely less on the ability of subways to promote growth and more on the demand for mobility. Our data also allows the first panel data estimates of the impact of changes in system extent on ridership and therefore also make an important contribution to such evaluations.

Understanding the effect of subways on cities is also important to policy makers interested in the process of urbanization in the developing world. Over the coming decades, we expect an enormous migration of rural population towards major urban areas and with it demands for urban infrastructure that exceed the ability of local and national governments to supply it. In order to assess trade-offs between different types of infrastructure in these cities, understanding the implications of each for welfare is clearly important. Since people move to more attractive places and away from less attractive ones (broadly defined), our investigation of the relationship between subways and population growth will help to inform these decisions. That subways have at most a tiny effect on population growth suggests that infrastructure spending plans in developing world cities should give serious consideration to non-subway infrastructure.

Finally, an active academic literature investigates the effect of transportation infrastructure on the growth and configuration of cities. In spite of their prominence in policy debates, subways have so far escaped the attention of this literature. This primarily reflects the relative rarity of subways. Most cities have roads so a single country can provide a large enough sample to analyze the effects of roads on cities. Subways are too rare for this. A statistical analysis of the effect of subways on cities requires data from, at least, several countries and an important contribution of this paper is to assemble data that describe all of the world’s subway networks. In addition, with few exceptions, the current literature on the effects of infrastructure is static or considers panel data that is too short to investigate the dynamics of infrastructure’s effects on cities. Because our panel spans the 60 year period from 1950 until 2010, we are able to investigate such dynamic responses to the provision of subways.

To estimate the causal effects of subways on urban growth and urban form, we must grapple with the fact that subway systems and stations are not constructed at random times and places. This suggests two potential threats to causal identification. The first could occur if subway expansions systematically take place at times when a city’s population growth is slower (or faster) than average, for example, if construction crews leave the city when new subway expansions are complete or if subway expansions tend to occur when some constraint on a city’s growth begins to bind. The second results from omitted variables. For example, suppose that cities expand their bus networks in years when they do not expand their subway networks and that bus and subway networks contribute equally to population growth. Then any regression of population growth on subway growth that omits a measure of the bus network will be biased downward. Briefly, we address the problem of confounding dynamics by showing that the null population growth result is invariant to using first differences, instrumented first differences, second differences and dynamic panel data models. The instrument we propose takes advantage of the fact that larger subway systems grow more slowly and this allows us to predict subway growth using long lags of subway system size. We address the omitted variables issue by showing that the null effect of subways on population is not masking heterogenous effects by measures such as congestion, road supply, bus supply, institutional quality, city size, or size of network, among others.

Download full version (PDF): Subways and Urban Growth

Tags: Brown University, Marco Gonzalez-Navarro, Matthew A. Turner, Population Growth, Subway, Subways, University of Toronto

RSS Feed

RSS Feed