RE:FOCUS PARTNERS

Three Case Studies in Stormwater Infrastructure Innovation

Introduction

It is apparent that cities across the United States are coping with aging and failing infrastructure systems. What is less apparent is that small cities often face many of the same overwhelming, chronic and costly infrastructure problems as big cities. However, most smaller cities and towns do not have the capacity, expertise or resources to address these challenges. Large cities, like New York and Los Angeles, have entire departments with dedicated budgets to tackle problems with aging water systems and deteriorating roads, for example. The City of Boston has a staff position for improving the city’s public procurement processes and outcomes. Through 100 Resilient Cities, one hundred mostly large and medium sized cities around the world have new “Chief Resilience Officers.” When innovation in infrastructure happens, it is often as a result of the hard work of these dedicated city officials, departments, and resources.

Very real barriers exist for all cities looking to implement systematic infrastructure upgrades, including the gap in predevelopment capacity and resources, challenges in public procurement, competing city priorities, the understandable risk-aversion of government officials and engineers, and of course, lack of funding.

Smaller cities have an added barrier to this already onerous list: simply because of their size, these cities often do not have the dedicated time, staff or resources to evaluate how to best upgrade their existing infrastructure systems to be smarter and more resilient. Even when there is strong political and community support, pursuing innovative infrastructure projects can be intimidating, requiring expensive consultants and time-consuming feasibility studies to develop and evaluate different alternatives. If and when small cities overcome these barriers and undertake public procurement processes, these cities rarely have the visibility to publicize calls for proposals to larger design, engineering, and construction firms.

This means that smaller cities are often stuck making incremental fixes to existing systems, replacing what they had, or in the worst cases, doing nothing. The result is taxpayer dollars spent on new infrastructure designed for yesterday’s (or more accurately, last century’s) challenges. Nowhere in the United States is the “small cities with big-city infrastructure problems” dilemma more apparent than in cities that have combined sewer and water systems. These combined sewer and water systems are the legacy of 19th and 20th century development patterns that have endured as cities have grown. In the 21st century, these combined systems create major health and environmental problems.

Over eight hundred communities in the United States have combined water and sanitary sewers. These combined systems transport household, commercial, and industrial wastewater along with storm water. As a result, these systems can overflow during periods of heavy rain or snowmelt, carrying untreated sewage and water into local and regional waterways. Associated environmental and health impacts can be severe; health impacts associated with exposure to these discharges include hepatitis, gastroenteritis, and other infections. The EPA and state environmental protection agencies have placed high priority on mitigating combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and have mandated major CSO reductions under the Clean Water Act.

It is estimated that the cost of reducing CSOs to comply with these mandates will run into the billions of dollars. For many smaller communities that are already resource constrained and coping with long lists of urgent priorities, water system retrofits will take decades and the costs of compliance are expected to place a tremendous burden on city and utility budgets.

The Case for Integrated Infrastructure Projects

Integrated infrastructure projects are one way for small and medium-sized cities to spur near-term action and innovation to solve overwhelming and seemingly intractable infrastructure challenges, such as addressing CSOs. Integrated infrastructure projects address multiple community problems in one cohesive design. For example, in 2016 the government of Hong Kong opened T-Park, a single project that incorporates a new waste-to-energy facility that combines sewage and wastewater treatment with desalinization, energy generation, and recreational amenities.

Although integrated planning might appear more complex that conventional project design and finance, pursuing cross-sector infrastructure projects can unlock new resources and build broader support for projects that would never move forward otherwise. Some of the benefits of integrated infrastructure design include:

- Unlock Nontraditional Funding and Financing

Integrated infrastructure projects solve multiple community problems. This means that a broader range of funding/ financing sources are often available, including resources that are not typically accessible for traditional projects. Integrated infrastructure solutions can also combine revenue-generating project components (i.e. energy generation) with those that create savings or other benefits (i.e. green infrastructure and recreational space) to expand the potential mechanisms available for implementation. - Creative Near-Term Political Wins

Integrated infrastructure projects often pair long-term, mostly invisible problems (like CSOs) with a shorter-term, more visible “pain point” (like a lack of parking). This means integrated infrastructure projects can generate clear and visible near-term benefits for the communities they serve. This visibility makes it easier to communicate a project’s necessity to citizens and business owners, and gain the support of elected officials for overall project completion. - Foster Innovation Through Uncommon Collaborations

Integrated infrastructure projects are, by their very nature, interdisciplinary, and require cross-sector collaboration. This means that stakeholders, departments, and people who do not frequently work together, like real estate developers and utility officials, must collaborate to achieve a common goal. These kinds of uncommon collaborations often lead to innovations and efficiencies that would not exist otherwise.

Taking an integrated approach to major infrastructure challenges offers all cities and utilities a new pathway to tackle high-priority projects while simultaneously leveraging resources and support for large-scale system change. This is especially important for cash-strapped small cities that don’t have access to the funding, financing, or implementation options available to larger cities to explore more modern or more sustainable technologies and solutions.

Download full version (PDF): Small Cities with Big-City Infrastructure Problems

About re:focus Partners

www.refocuspartners.com

The re:focus approach is based on the idea that designing new types of projects—not just building or funding more of the same—is essential. By crafting large-scale solutions that generate multiple benefits and revenue opportunities, re:focus aims to leverage public funding for infrastructure and attract additional private financing, even in areas where traditional projects face significant barriers to implementation.

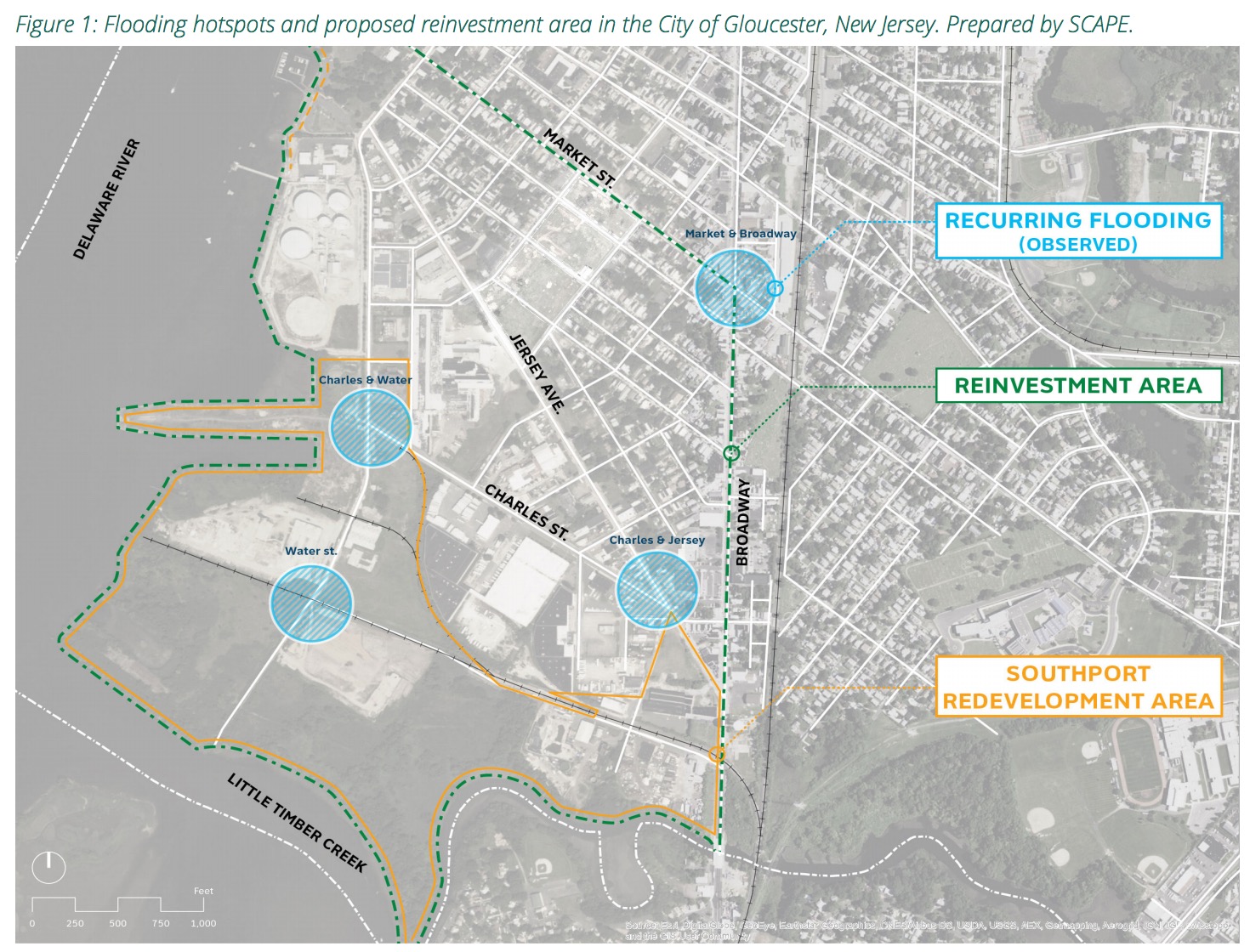

Tags: Gloucester, New Jersey, NJ, re:focus, RE:Focus Partners, stormwater

RSS Feed

RSS Feed