NATIONAL RENEWABLE ENERGY LABORATORY

Executive Summary

This report provides a high-level overview of the current U.S. shared solar landscape and the impact that a given shared solar program’s structure has on requiring federal securities oversight, as well as an estimate of market potential for U.S. shared solar deployment. Shared solar models allocate the electricity of a jointly owned or leased system to offset individual consumers’ electricity bills, allowing multiple energy consumers to share the benefits of a single solar array. Despite tremendous growth in the U.S. solar market over the last decade, existing business models and regulatory environments have not been designed to provide access to a significant portion of potential PV system customers. As a result, the economic, environmental, and social benefits of distributed PV are not available to all consumers. Emerging business models for solar deployment have the potential to expand the solar market customer-base dramatically. Options such as offsite shared solar and arrays on multi-unit buildings can enable rapid, widespread market growth by increasing access to renewables on readily available sites, potentially lowering costs via economies of scale, pooling customer demand, and fostering business model and technical innovations. Fundamentally, these models remove the need for a spatial one-to-one mapping between distributed solar arrays and the energy consumers who receive their electricity or monetary benefits. The output of shared solar arrays can be divided among residential and commercial energy consumers lacking the necessary unshaded roof space to host a PV system of sufficient size, or divided among customers seeking more freedom, flexibility, and a potentially lower price.

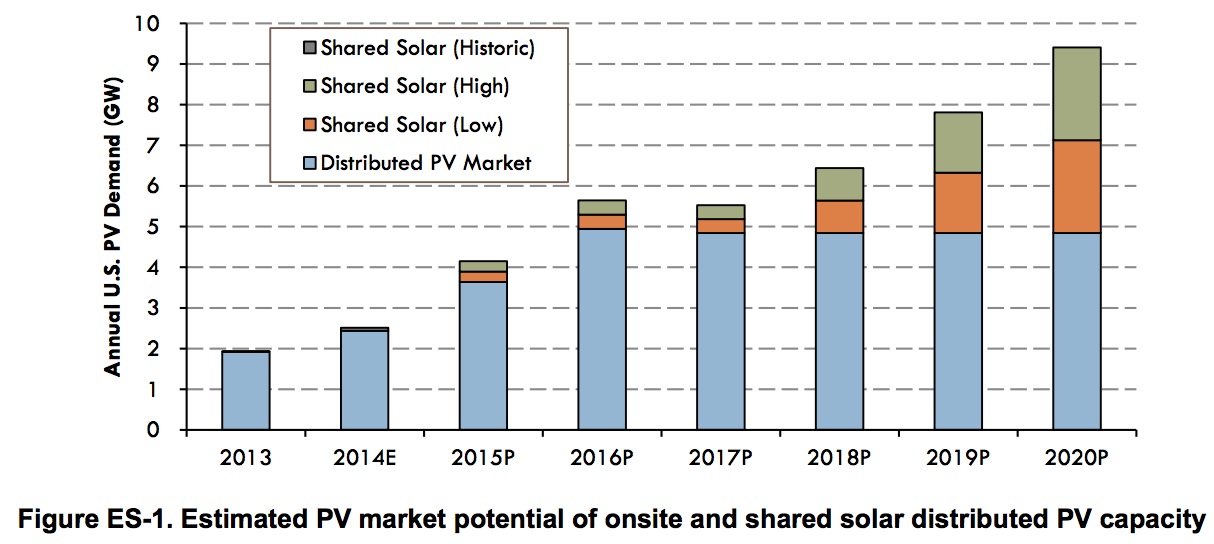

If federal, state, and local policies can institute a supportive regulatory environment, shared solar presents an area of tremendous potential growth for solar photovoltaics (PV), expanding the potential customer base to 100% of homes and businesses. We estimate that 49% of households are currently unable to host a PV system when excluding households that 1) do not own their building (i.e., renters), 2) do not have access to sufficient roof space (e.g., high-rise buildings, multi-unit housing), and/or 3) live in buildings with insufficient roof space to host a PV system. We also estimate that 48% of businesses are unable to host a PV system when excluding businesses that 1) operate in buildings with too many establishments to have access to sufficient roof space (e.g., malls), and/or 2) have insufficient roof space to host a PV system capable of supplying a sufficient amount of their energy demand. By opening the market to these customers, shared solar could represent 32%–49% of the distributed PV market in 2020, thereby leading to growing cumulative PV deployment growth in 2015–2020 of 5.5–11.0 GW, and representing $8.2–$16.3 billion of cumulative investment (Figure ES-1).

There are several factors that may cause shared solar deployment to be significantly higher than these estimates, including easier and less restrictive participation, a better value proposition through economies of scale, and the ability to service a much higher share of customer load. That said, without proper legislative support from federal, state, and local authorities as well as further business innovation and expansion, shared solar may have difficulty reaching these deployment levels.

Shared solar arrays can be hosted and administered by a variety of entities, including utilities, solar developers, residential or commercial landlords, community and nonprofit organizations, or a combination thereof. Electricity benefits are typically allocated on a capacity or energy-production basis. Participants in capacity-based programs own, lease, or subscribe to a specified number of panels or a portion of the system and typically receive electricity or monetary credits in proportion to their share of the project.

Shared solar enabling state legislation commonly takes the form of virtual net metering (VNM), specific tariffs, or holistic statewide shared clean energy programs that incorporate VNM or a set tariff. VNM and on-bill credits enable the allocation of benefits from an electricity-generating source that is not directly interconnected to the energy consumer’s electricity meter. Federal tax credits that support PV deployment historically have been designed for use by a single entity; shared solar projects that involve multiple entities can pose challenges to allocating tax-credit benefits. However, in some instances, shared solar programs can function similarly to single-entity solar projects for tax-credit purposes.

Despite regulatory frameworks that make shared solar available in many states and jurisdictions, the shared solar business model still faces barriers to greater adoption. Owing to the infancy of the market, there is a lack of legal precedent, market research, and data on project successes. One of the top concerns raised by shared solar stakeholders is uncertainty about the applicability of Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requirements for registration and disclosure of shared solar projects. Central to this issue is whether an interest in a shared solar project is a “security.” If it is, then it is regulated by the SEC (although its offer may qualify for an exemption) and has the potential to significantly impact the way a shared solar program operates. Therefore, stakeholders should consider securities regulations carefully when structuring a shared solar program.

One central question in determining whether participation in a shared solar project is considered a security appears to be the motivation of the participant and the perception of the participation. SEC Staff have provided some guidance on this issue through a no-action letter issued to the solar developer CommunitySun, LLC and through individual discussions with the authors of this paper. Based on this information, participation in a shared solar project likely will not be considered an investment contract and may not otherwise be a security when participants’ primary motivation for participating in the shared solar project is personal consumption (i.e., reducing a customer’s retail electricity bills)—not the expectation of profit—and the terms of participation include certain provisions to prevent the use of the agreement as a financial play.

Shared solar offerings that are classified as securities can still be bought and sold if they are registered with the SEC and follow more stringent procedures or if they qualify for an exemption. The most relevant exemptions for shared solar programs are Regulation D, including Rule 506 (CFR, §230.506) (more specifically, 506(b) and 506(c)) and Rule 504 (CFR, §230.504), the intrastate exemption, and exemptions related to nonprofits. Shared solar projects that avoid SEC regulation by not being considered a security or by qualifying for an exemption may be subject to regulation by other federal, state, and local laws. For example, every state has its own set of securities statutes, which may treat securities differently from federal law. Also, while the SEC has provided some guidance on this issue, judicial authority supersedes administrative guidance.

As these new business models and legal frameworks are established, working within the guidance of SEC interpretation of securities law will create more confidence in the shared solar market, and ideally, it will reduce restrictions, delays, and costs.

Download full version (PDF): Shared Solar

About the National Renewable Energy Laboratory

www.nrel.gov

At NREL, we focus on creative answers to today’s energy challenges. From breakthroughs in fundamental science to new clean technologies to integrated energy systems that power our lives, NREL researchers are transforming the way the nation and the world use energy.

Tags: National Renewable Energy Laboratory, NREL, Solar, Solar Energy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed