COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS

Road to Nowhere: Federal Transportation Policy

Introduction

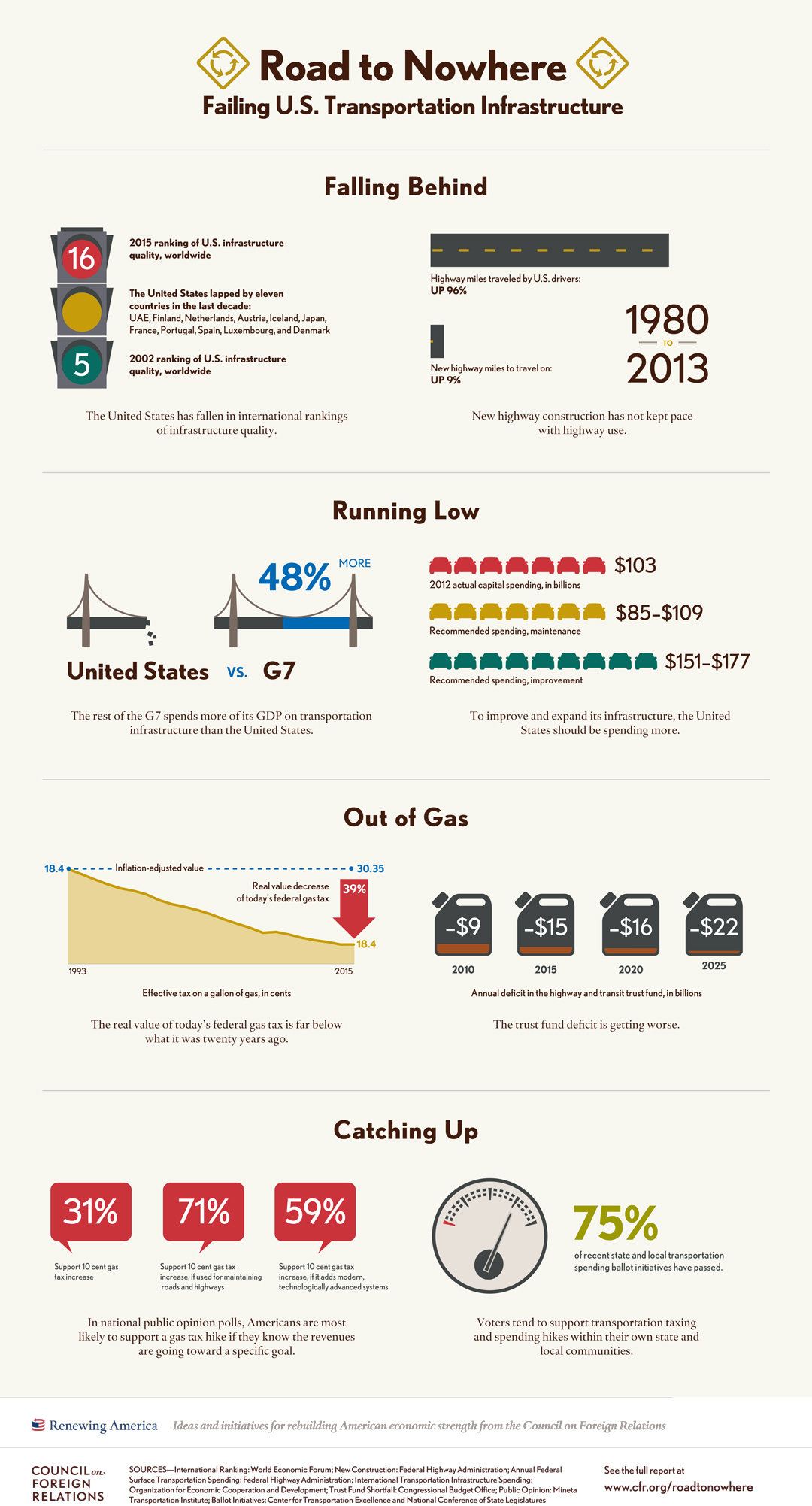

The United States has a transportation infrastructure funding problem. The way the federal government raises money to pay for highways and transit no longer works, leading to budget shortfalls and underinvestment in infrastructure. Drivers pay a federal gas tax, with those revenues placed in trust funds dedicated solely to pay for highway, roads, and transit. But the gas tax is not producing as much revenue as it did in the past, and Congress has struggled to find a solution for plugging the gap. Congress has either resorted to multi-month patches or used funding gimmicks to try to close the shortfalls. Since 2002, highway and transit funding has been declining in real terms for all levels of government, and the biggest drop-off is at the federal level.

In the face of federal inaction, states and localities have raised their own gas and sales taxes to pay for transportation investments. Politicians from across the political spectrum have supported using more public-private partnerships (P3s) to take some of the burden off the public sector. But private financing only works for a limited number of projects that have a high enough rate of return. Transportation infrastructure is a public good, and public dollars should make up the lion’s share of the investment gap. Ultimately, the American people will have to spend more to pay for their infrastructure.

Other peer countries are doing a better job at securing funding to pay for multiyear investment plans. Even conservative governments in the UK and Canada have pushed through big long-term funding increases. And whereas the federal government hands out the vast majority of transportation dollars via formula without any accountability for how they are spent, other countries make more needs-based and strategic investment decisions—which is especially important when budgets are lean.

Transportation Infrastructure and the Economy

Moving people and goods efficiently matters for the U.S. economy. Workers need to get to and from their jobs with ease and without wasting time sitting in traffic. Faster and more reliable on-time deliveries mean supply chains can be more dispersed and with less inventory standing time. All this energizes the economy. Infrastructure projects can also directly create jobs, especially for construction workers. With interest rates remaining at historic lows, an opportunity exists to marry short-term job creation with investments that will pay long-term benefits to U.S. economic competitiveness.

Compared with other kinds of public spending, infrastructure investment tends to have a larger stimulating effect on the economy, called a multiplier effect, and the effect is largest during a recession.1 According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), of all the spending and tax relief components to the 2009 stimulus package, the infrastructure component delivered among the greatest boost. One stimulus dollar spent on infrastructure was estimated to boost the economy by as much as just over two dollars.

Where the United States Stands

Quality: Average Among Peers

U.S. transportation infrastructure is mediocre compared with its peer competitors in the G7. For overall infrastructure quality, the United States used to rank fifth in the world; now it ranks sixteenth. Japan, Germany, and France consistently rank higher than the United States in road and rail quality—at least according to surveys of their citizens who use them day to day.3 Only for airports does the United States come out on top among G7 countries. International comparisons are difficult and perhaps not totally fair; the United States has a much larger geographic area to cover and lower population densities to serve than most other advanced countries. Globally, it has the most paved roads, rail tracks, and airports.

For surface transportation like roads, highways, and transit—where roughly 90 percent of all American travel-miles occur and where 85 percent of federal transportation funding is spent—government monitors suggest conditions are not getting worse.5 Between 2000 and 2010, average pavement conditions actually improved and driving fatality rates declined. The number of deficient bridges has been decreasing since the 1970s, though future repairs may not go as smoothly as in the past. The easy fixes have been crossed off the list, but several tricky, giant, and expensive bridges—like the Tappan Zee Bridge near New York City and the Columbia River Bridge near Portland, Oregon—are in urgent need of repairs.

Even if maintenance is up to date, capacity is not expanding as quickly as it should. Since 1980, the U.S. population has grown four times faster and vehicle miles traveled have grown ten times faster than new lane construction.6 The average American is driving slightly less than ten years ago. But total miles driven in the country, which had gone down during the recession, hit record highs once again in 2015.

Roads have become more congested. Compared with twenty years ago, the average American spends twice as much time, or forty-two hours a year, stuck in traffic (see figure 1).8 In the major metropolitan areas that fuel the nation’s economy, traffic is far worse. In Washington, DC, each driver loses eighty-two hours a year in traffic. The annual cost to the economy in fuel, wear, and wasted worker time tallies to $160 billion nationwide.

Some wild cards could see future capacity needs veer from the historical trend. The number of cars on the road could decrease if car-sharing services take off. Driverless or automated cars loaded with sensors may need less distance from other cars, squeezing more use out of existing capacity. Traffic sensors could relay information to these cars to send them along the most efficient route.

Download full version (PDF): Road to Nowhere Progress Report

About the Council on Foreign Relations

cfr.org

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government officials, business executives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other countries.

Tags: CFR, Council on Foreign Relations, Progress Report, Renewing America, Report Card

RSS Feed

RSS Feed