AMERICAN PLANNING ASSOCIATION

This paper summarizes the findings of a symposium and research on the implications of autonomous vehicles for cities and regions. It is intended for planners and local government officials involved in land-use planning, urban design, and transportation. Readers will learn about the need to plan for the potential benefits and negative impacts of autonomous vehicles and what steps they can take now to prepare their communities.

I. Introduction

Author: Jennifer Henaghan, AICP

On October 6, 2017, 85 thought leaders in planning, transportation, and related fields gathered at the National League of Cities (NLC) headquarters in Washington, D.C., to discuss how to plan for the impacts of autonomous vehicles (AVs) on cities and regions. This event was convened by the American Planning Association (APA), NLC, Mobility e3, George Mason University, Mobility Lab, the Eno Center for Transportation, and the Brookings Institution. Its purpose was to identify planning, policy, and research directions and needs to prepare cities and regions for a revolutionary new technology that will transform the way we think about transportation, transit, and land use.

Planners need to be thinking about AVs because of the significant impacts they will have on our communities. There are potential positive benefits as well as potential negative impacts, but none of these are assured. The secondary impacts are even more of an unknown. Working with other professionals, planners have an important role to play in helping communities maximize the benefits and minimize the negative impacts of the technology.

AVs have the potential to save lives by preventing accidents caused by driver error (including distracted driving), which claimed nearly 40,000 lives on American roads in 2016, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and they could allow for more efficient vehicle movement gained by closer vehicle spacing. They could provide “first and last mile” and “last 50 feet” connectivity to transit increasing mobility options for people with disabilities, seniors, and children. And they are expected to free up vast amounts of land currently used for parking.

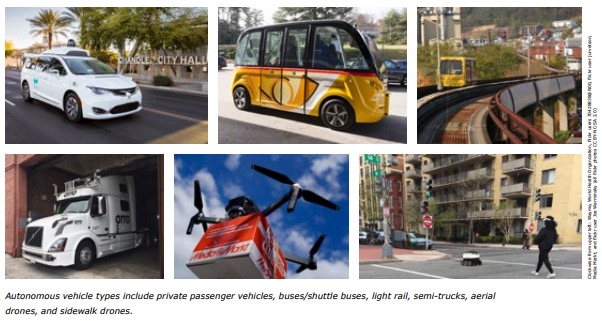

However, AVs are not guaranteed to produce uniformly positive interactions between humans and the built environment. They may end up increasing congestion if people shift from transit to personal autonomous vehicles. If people rely on AVs for door-to-door transportation, they may walk less. This may initiate a cycle of reduced local requirements for sidewalks and crosswalks that further discourages the choice to walk, creating negative health and social impacts. There will certainly be impacts on workers in the transportation field, as people who drive buses, trucks, and cars for a living stand to lose their jobs. And there are bigger-picture concerns with regard to privacy, data security, and personal safety if technology companies drive AV-related policies.

Autonomous vehicles are going to change our cities and regions, and those changes will come sooner rather than later. Most prognosticators agree that it will be decades before AVs are the dominant form of transportation, but pilot programs and commercial applications are rolling out faster than expected. Although their adoption time lines vary as to when their vehicles will be on the highways or in urban conditions, 11 of the largest automakers plan to have fully autonomous vehicles on the road between now (in the case of Tesla) and 2021.

The ongoing (and rapidly increasing) adoption of autonomous vehicle technology will have a profound impact on the way our communities look and feel. It’s clear that a change is coming, but what’s less clear is what, precisely, that change will mean. At this point, there are many more questions than there are answers.

Shared Use versus Private Ownership

Many of the potential benefits and costs of AVs hinge on whether the predominant model is shared use (resulting in fewer cars and less congestion) or private ownership of single-occupancy and “zero-occupancy” vehicles (resulting in more cars, more congestion, and diminution of other transportation modes). Vehicle miles traveled (VMT) may increase under any scenario, meaning that electrification of the AV fleet will be imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. How can markets move from privately owned automobiles powered by fossil fuels to a predominantly shared use, electric vehicle model?

Land-Use Patterns

There is a great deal of concern that AVs may encourage sprawl, but they also provide potential opportunities for “sprawl repair.” New urban/suburban districts may be more efficient for transit, energy production/distribution, and stormwater management. Forward-thinking cities and regions could create mobility hubs to aggregate and provide seamless transfer across a growing number of options and partnership models. As mobility shifts, how will we determine value capture (similar to transitoriented development (TOD))?

Right-of-Way Size and Usage

Autonomous vehicles require less road space than a manually driven vehicle, as their ability to communicate with the transportation network as well as each other allow them to operate with a smaller following distance and in narrower lanes. As a result, future roads will require less pavement width and existing roads may be adapted. Will the “extra” space gained by this transition be used for transportation enhancements (such as bike lanes, pedestrian paths, transit ways, on-street parking) or park space, or will it be transferred to the adjacent property owners?

Traffic Management

Traffic signals, signs, and street markings will likely need to change to accommodate autonomous vehicles, especially where they can help reduce potential conflicts between vehicular traffic and nonmotorized road users, such as cyclists and pedestrians. These will also be important during the transitional phase where AVs and non-AVs share the roadway. Optimizing a roadway for AVs will also require the installation of various types of sensors and communications technology to allow vehicles to travel more efficiently. Who will pay for the installation of AV-friendly traffic management systems?

Related Infrastructure

Large numbers of autonomous vehicles on city streets will generate additional types of infrastructure needs. Communications networks based on available wifi will be crucial not just to vehicles, but also to the occupants who will be free to teleconference, access the internet, and enjoy other activities instead of needing to watch the road. Who will install infrastructure and provide service on these wifi networks?

Similarly, assuming that future AVs will largely (if not entirely) be electric vehicles, where and when will they charge, and how will this impact the power grid?

Liability

Smart transportation systems will rely on a complex interaction between mechanical vehicles, the software within those vehicles, the software and available technology within the roadways, and people. Who will be liable when an accident occurs, and how will this affect insurance requirements?

Economy

Millions of truck drivers, delivery people, taxi drivers, rail workers, and transit workers will likely see their current jobs change significantly, or outright disappear, as AVs remove the need for a person to physically move goods and people from place to place. What further impact will this have on the transportation industry?

Equity

Semiskilled labor and blue-collar jobs will likely see the highest impact from a shift to AVs. Public transportation could be supplanted by private alternatives (such as ride sharing), which could leave residents of low-income neighborhoods stranded. While AVs could increase mobility for persons with disabilities and seniors, such gains are not assured. Most discussion of AVs has focused on urban environments and it is unclear how low-density and rural areas will be affected. How can AV policies reduce inequities or, at the very least, not increase them?

We discuss the above questions in this report, plus many more related to issues such as municipal operations and finances, parking and revenue, environmental impact, and land use and urban design. We offer a framework for use by planners and their colleagues in local government as they seek to answer these questions and prepare communities and regions for the onset of AVs.

The paper contains three main chapters following this introduction. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the current state of AV technology and the federal and state policy context. Chapter 3 summarizes the discussions from the symposium, focusing on three primary themes: equity and access, the transportation network, and land use and development. Chapter 4 provides guidance on how planners and local and regional government agencies can begin planning for the impacts of AV, using APA’s strategic points of intervention (community visioning and goal setting; plan making; regulations, standards, and incentives; site design and development; and public investment) as a framework. The report concludes with an identification of future research needs (Chapter 5), followed by a comprehensive list of references and resources.

Download full version (PDF): Preparing Communities for Autonomous Vehicles

About the American Planning Association (APA)

planning.org/

The American Planning Association provides leadership in the development of vital communities by advocating excellence in planning, promoting education and citizen empowerment, and providing our members with the tools and support necessary to meet the challenges of growth and change.

Tags: American Planning Association, APA, Autonomous Vehicles, driverless cars, Jennifer Henaghan

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Much misplaced confidence in merely a concept. Where are the concrete examples? Elevators are autonomous vehicles. Why are they already ubiquitous in high rises? Because of their safety, reliability, and effectiveness. Most proposals widely known have little merit, among them autonomous cars and drones, Uber delivery, sidewalk boots, etc. CargoFish has merit.