DELOITTE CENTER FOR ENERGY SOLUTIONS

Introduction: The future is electric

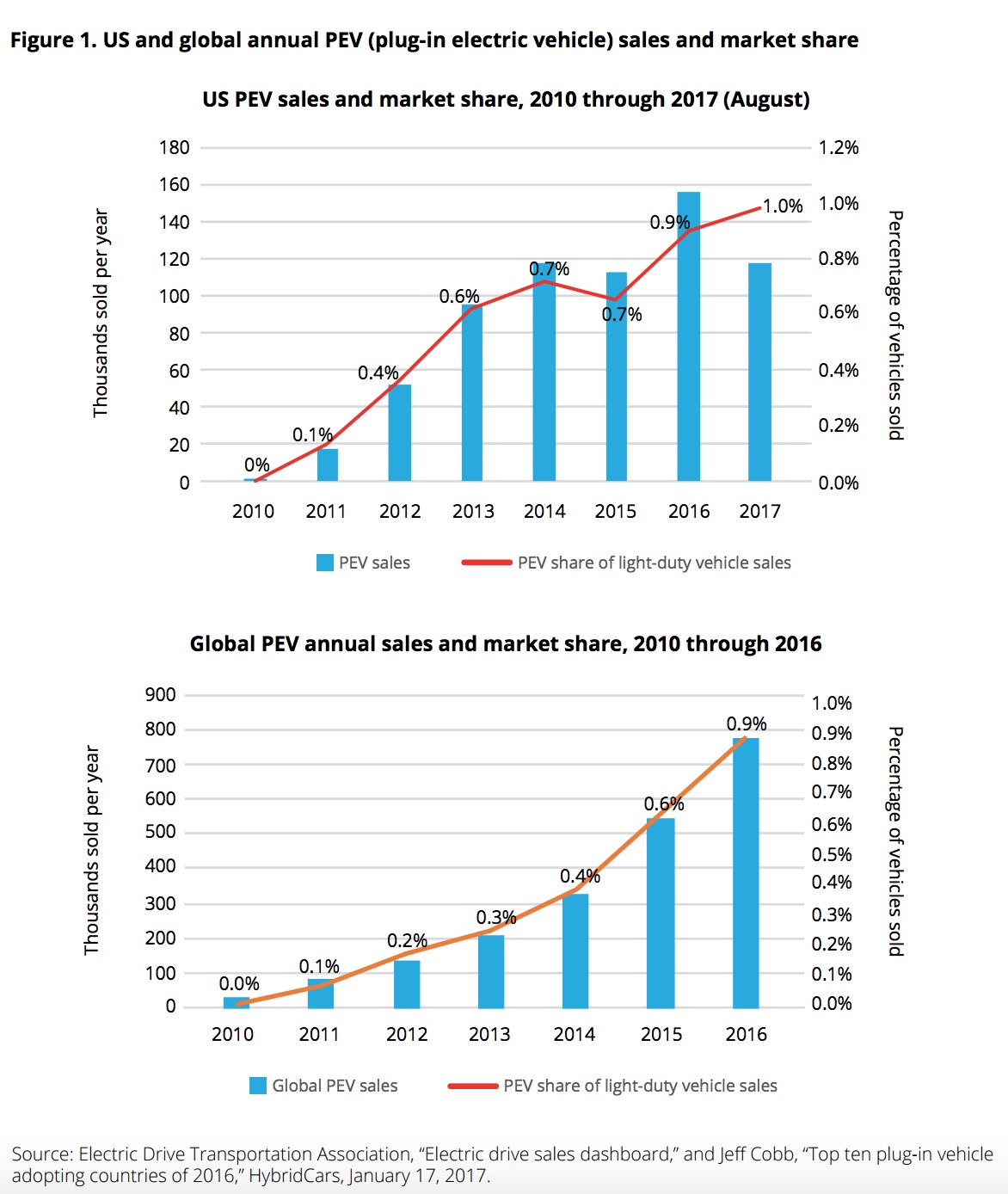

ANALYSTS have long predicted that car and fleet owners would soon abandon traditional fossil-fuel-powered vehicles and go electric.1 But after years of hype, promotion, and government incentives, electric vehicles (EVs) represent barely 1 percent of the market, both globally and in the United States.

ANALYSTS have long predicted that car and fleet owners would soon abandon traditional fossil-fuel-powered vehicles and go electric.1 But after years of hype, promotion, and government incentives, electric vehicles (EVs) represent barely 1 percent of the market, both globally and in the United States.

And yet the optimistic forecasts might turn out to have been only a bit early, with rapid EV adoption— finally—just around the bend. Consumers are increasingly opting for electric cars, as factors such as falling prices, increasing range, and appealing incentives combine with the “cool factor” created when exceptional design meets advanced technologies. On the horizon, the future of mobility—in particular carsharing, ridesharing, and autonomous vehicles—strongly complements EVs, further hastening adoption.

The new mobility ecosystem is arriving none too soon for the electric power industry in the United States and elsewhere. Electric companies face a variety of challenges—among them, flat electricity demand and the need to smoothly integrate a growing pool of distributed and renewable energy resources. Utilities continue to search for a “killer app” to more deeply engage customers and interest them in new products and services. A rapidly expanding EV fleet could help address each of those challenges.

And even though other sectors are making higher-profile moves as the future of mobility becomes a reality—from groundbreaking vehicle designs2 to flashy entertainment options3 —electric companies need not passively wait for consumers to begin plugging in rather than filling up. To accelerate EV adoption, electric companies can do more to educate and incentivize customers to purchase electric cars, and they have the opportunity to become major players in the buildout of EV charging infrastructure (wired and eventually wireless). They can also brace for the increased electricity demand and changing load patterns by preparing to manage and control new EV load through smart grid technologies.

This article explores how a growing electric vehicle fleet, accelerated by other mobility trends such as shared and self-driving cars, could affect power and utility companies’ possible choices. We lay out why EV adoption may be at an inflection point, examine how the emergence of a new mobility ecosystem could create a symbiotic relationship between EVs, autonomous vehicles, and ridesharing, and look at how electric companies might turn these trends to their advantage. Last, informed by a new Deloitte survey of industry executives, we lay out some of the key steps utility executives can begin taking now to capitalize on an increasingly electric future of mobility.

Have EV sales reached a tipping point?

CAR buyers and fleet owners across the globe are starting to give electric vehicles a second look. Why? Because new showroom arrivals have altered the initial perception of batterypowered cars as short-range, low-speed capsules. Futuristic, high-tech EVs that are fun to drive have changed consumer perceptions, with many now seeing them as the hip, desirable car of the future.4 As important, plummeting battery prices have enabled automakers to introduce new, more walletfriendly models with longer ranges.5 An estimated 30–40 percent of an EV’s cost is in the lithium-ion battery pack that powers it. But those costs are falling fast, down 73 percent between 2010 and 2016 to $273 per kilowatt-hour. Prices continue to fall due to technological improvements, manufacturing cost reductions—especially as production scales up— global manufacturing overcapacity, and competition.6 At the same time, gradual buildout of charging infrastructure is helping to allay some buyers’ “range anxiety.”7 And, with the projected growth of carsharing and ride-hailing services, range anxiety is likely to be less of a constraint for fleet management companies that can closely monitor and control EV charging.

Many governments have long incentivized EV purchases, but Norway, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, and others8 have recently announced even more ambitious goals of ending or severely curtailing sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles within the next decade or two. China, with total annual car sales approaching 30 million, is working out a timetable to ban ICE vehicle sales completely.9 India has set its sights on the same goal by 2030, which may be ambitious as it would require annual sales to exceed 10 million EVs, but it will likely add momentum to the global shift toward EVs.10 While stopping short of banning ICE vehicles, 10 US states, citing environmental concerns, have set aggressive goals to increase EV sales.11 Even if they fall short of those targets, automakers will be forced to reckon with these policies as they roll out new models, and the net effect is likely to be many more electric cars on the road.

Together, these developments are accelerating EV adoption across the globe, even as the vehicles’ share of overall sales remains small (see figure 1).

How quickly is this likely to change? Projections for US and global EV market-share growth over the next two decades vary widely, from as low as 10 percent to more than 50 percent by 2040 (see figure 2).13 Where the actual numbers fall in the end is likely to depend on government policies to encourage EV adoption, and on the number and cost of new EV models available, as well as emerging trends in personal mobility.

The advances in electric vehicles are part of a much broader transformation of the extended auto industry into a new mobility ecosystem (see sidebar, “What is the future of mobility?”). Critically, two of those trends—the growth of shared mobility and the emergence of self-driving vehicles—share many complementarities with electric vehicles, and may well further accelerate EV growth:

- Reduced operating costs. With high-utilization ridesharing fleets, EVs’ low operating costs compared with conventional ICE vehicles become an economic advantage. The growth of ridesharing and ride-hailing services will likely lead to higher utilization rates: both more miles driven and more daily road hours per car. New mobility management or mobility-as-a-service companies may own fleets of vehicles that circulate almost continuously, with or without drivers, picking up passengers who have hailed them, typically through smartphone apps. Autonomous ride-hailing vehicles may be used about 40 percent of the day, compared with less than 5 percent for privately owned vehicles.15 And research shows that the more miles a car drives in its lifetime, the more economical it is to drive electric due to the lower costs of charging relative to refueling and the reduced maintenance expenses that accompany simpler construction.

- Autonomous technology integrates better with electric engines. Electric cars are easier for computers to drive—indeed, most EVs are built with driveby-wire systems that replace traditional mechanical control systems with electronic controls, and these systems create a more compatible and flexible platform for autonomous driving technologies. In addition, EV battery packs contain higher voltages than typical ICE vehicle batteries, which enable them to accommodate more self-driving features. While engineers can make gasoline-powered cars autonomous, automakers and technology companies have largely chosen EVs—with far fewer moving parts—for their self-driving vehicle prototypes.

- Safety and design simplicity. If a self-driving ICE vehicle pulled up to the gas pump, it would likely need human assistance to fill the tank; recharging a driverless EV would likely be easier and safer. While EV manufacturers have been developing automated chargers that would plug into self-driving cars, the industry generally expects that wireless charging, which some automakers are already bringing to market, will be the more likely solution.18 A self-driving EV could navigate to the nearest wireless charging pad (or utilize in-road charging infrastructure), park itself, charge, and then drive away—or even charge itself while waiting at a traffic light or to pick up a passenger. Automakers see wireless charging as a convenience that will likely help increase electric vehicle adoption.

Early prototypes and pilot programs of ridesharing autonomous vehicle services are already heavily favoring EVs. For example, General Motors designed its Bolt EV specifically for ridesharing and mobility services, according to GM’s executive chief engineer of autonomous tech. Ridesharing service Lyft, which is partnering with several automakers, aims to provide at least 1 billion rides per year using electric autonomous vehicles by 2025, and to power those cars with “100% renewable energy.”

Download full version (PDF): Powering the future of mobility

About the Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions

www2.deloitte.com

Energy tops the agenda for governments and businesses around the world. Fluctuating demand, constrained supply, volatile commodity prices, and changing regulatory environments are a few of the critical issues contributing to the complexities of today’s energy industry. The Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions provides comprehensive solutions and services to help companies navigate through this environment to achieve sustainable, profitable growth.

Tags: Deloitte Center for Energy Solutions, Electric Vehicles, EVs, Ridesharing

RSS Feed

RSS Feed