MIT DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING

Introduction

On a September afternoon, jazz music and barbecue smoke fills the air of a century-old urban market, rising to the rafters to mix with the pleasant din of hundreds of small conversations. Detroit’s Eastern Market is one of the few bright spots of vibrancy and activity in a city that can often feel abandoned.

On a September afternoon, jazz music and barbecue smoke fills the air of a century-old urban market, rising to the rafters to mix with the pleasant din of hundreds of small conversations. Detroit’s Eastern Market is one of the few bright spots of vibrancy and activity in a city that can often feel abandoned.

Here, community is nourished, literally, as Detroit residents and visitors of all descriptions peruse rows of fresh vegetables, stopping to chat with merchants and each other. A week later, the adjacent cities of Fargo, ND and Moorhead, MN host an event that brings people of all ages to the streets to bike, walk, rollerblade, and meet their neighbors. This same month, residents and public officials take a two-hour walk down 35th Street in Norfolk, VA to discuss a vision for a temporary event that will highlight popup businesses, open space, and new ways of celebrating community. In Denver, the small business owners and office workers of TA XI, an unorthodox mixed-use office park on an industrial stretch of the city’s Platte River, gather for after-work cocktails and conversation on the deck of a shipping-container pool overlooking a freight train yard.

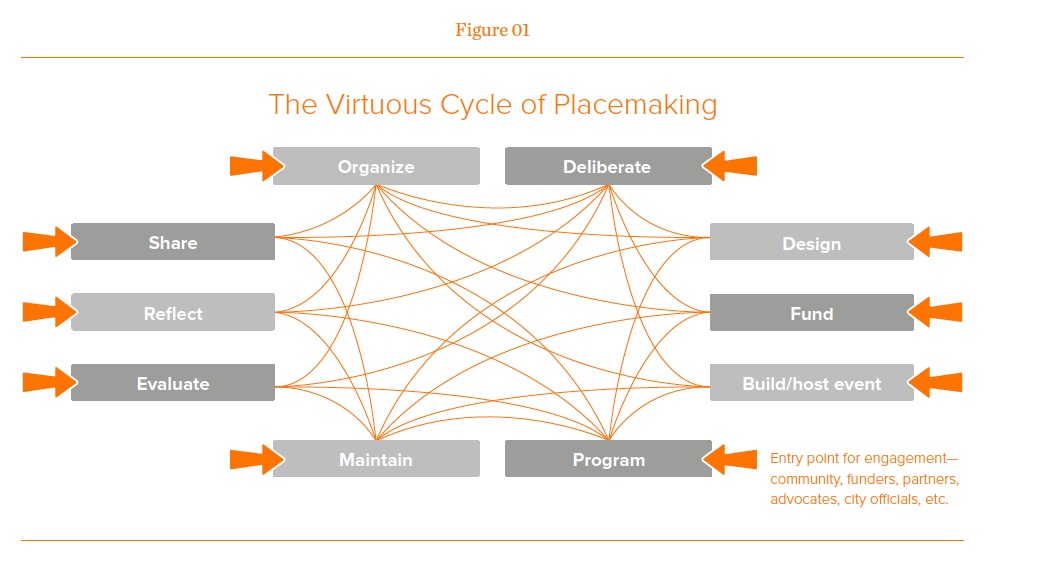

All of these scenes illustrate a community coming together in a physical environment created by a process of placemaking. The practice concerns the deliberate shaping of an environment to facilitate social interaction and improve a community’s quality of life. Placemaking as we now know it can trace its roots back to the seminal works of urban thinkers like Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch and William Whyte, who, beginning in the 1960s, espoused a new way to understand, design and program public spaces by putting people and communities ahead of efficiency and aesthetics. Their philosophies, considered groundbreaking at the time, were in a way reassertions of the people-centered town planning principles that were forgotten during the hundred-year period of rapid industrialization, suburbanization, and urban renewal. Placemaking may come naturally to human societies, but something was lost along the way; communities were rendered powerless in the shadows of experts to shape their physical surroundings.

Since the 1960s, placemaking has grown up. What began as a reaction against auto-centric planning and bad public spaces has expanded to include broader concerns about healthy living, social justice, community capacity-building, economic revitalization, childhood development, and a host of other issues facing residents, workers, and visitors in towns and cities large and small. Today, placemaking ranges from the grassroots, one-day tactical urbanism of Park(ing) Day to a developer’s deliberate and decades- long transformation of a Denver neighborhood around the organizing principle of art. Governmental organizations such as The National Endowment for the Arts and New York City’s Department of Transportation, civic organizations like the Kinder Foundation, and funders such as Blue Cross Blue Shield have embraced placemaking, just to name a few. Conferences on the topic have been held, and well attended, in the last year by the Urban Land Institute, the Institute for Quality Communities, Project for Public Spaces©, and others. Placemaking has hit the mainstream.

This is news to no one in the field; the array of placemaking projects, out comes and actors is large and strikingly diverse. The term encompasses a growing number of disciples and rapidly expanding roster of projects. Though this diversity is beneficial, the sheer number of projects that fall under the placemaking rubric can be overwhelming for scholars and practitioners, not to mention funders. The recession that began in 2008 has shown once again that planning, like economics, deals with the allocation of scarce resources. New political, economic and social realities demand that placemaking have measureable impacts on economic, social and health outcomes. Placemaking advocates in all sectors are challenged to measure positive outcomes to justify expenditures in a field of practice where goals are often nebulous and attempts to measure impacts are nascent at best.

Placemaking today is ambitious and optimistic. At its most basic, the practice aims to improve the quality of a public place and the lives of its community in tandem. Put into practice, placemaking seeks to build or improve public space, spark public discourse, create beauty and delight, engender civic pride, connect neighborhoods, support community health and safety, grow social justice, catalyze economic development, promote environmental sustainability, and of course nurture an authentic “sense of place.” The list could go on. Many of these attributes have been well documented and well theorized over a half-century of research into what makes a great public place. While these efforts are valuable, the tendency to focus on the physical characteristics has created a framework for practicing, advocating for, and funding placemaking that does disservice to the ways the placemaking process nurtures our communities and feeds our social lives.

Download full version (PDF): Places in the Making

About the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning

dusp.mit.edu

“Over the past half-century, developed countries have experienced rapid urbanization around their edges and deindustrialization in their cores; economic restructuring has had uneven impacts between and within regions. In decades to come, most of the world’s urbanization will occur in the metropolitan regions of Africa, Latin America and Asia, in settlements that lack the infrastructure, resources, and organization to cope with the challenges that confront them. Over the same period, the United States will add over 100 million new residents to metropolitan areas that are increasingly ethnically diverse and persistently unequal, and whose postwar infrastructure is largely crumbling. Cities worldwide will have to deal with climate change, large-scale migration, changes in family structure, rapid technological change, and other powerful forces.

As a department, we can address many, but not all, of the challenges associated with urban development in the twenty-first century. To this end, we must build on our strengths in design and physical planning in order to focus on five critical areas. Each of these domains reflects a globalized world and offers rich opportunities for learning through research, teaching, and engagement in the field. Each domain requires collaboration across disciplines and specializations in our department, thinking and doing at multiple scales (neighborhood, city, region, national, global), and significant innovation in the ways in which we train professionals and define excellence in practice.”

Tags: Department of Urban Studies and Planning, DUSP, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MIT

RSS Feed

RSS Feed