US WATER ALLIANCE

This is one in a series of policy briefs that comprise the One Water for America Policy Framework. To download an Executive Summary, additional policy briefs, or learn how you can get involved, please visit: www.uswateralliance.org/initiatives/listening-sessions.

America’s water supplies and services are at risk. Climate change, growing income disparities, and the threats posed by our aging water infrastructure call into question the continued availability of safe water supplies and reliable, affordable water service. In light of these challenges, we must come together and create a new era of water management in America—one that secures economic, environmental, and community wellbeing.

To that end, the US Water Alliance worked with more than 40 partner organizations to host 15 One Water for America Listening Sessions across the country. These discussions engaged more than 500 leaders, including water utility managers, public officials, business executives, farmers, environmental and watershed advocates, community leaders, philanthropic organizations, planners, and researchers.

What we heard from these stakeholders was truly inspiring. Across the nation, people from all walks of life are collaborating and innovating to advance sustainable water management solutions. Now is the time to spread and scale up these successes to benefit more communities across the country. In these seven policy briefs, we have compiled the strongest, most consistent themes from the One Water for America Listening Sessions into seven big ideas for the sustainable management of water in the United States:

- 1. Advance regional collaboration on water management

- 2. Accelerate agriculture-utility partnerships to improve water quality

- 3. Sustain adequate funding for water infrastructure

- 4. Blend public and private expertise and investment to address water infrastructure needs

- 5. Redefine affordability for the 21st century

- 6. Reduce lead risks, and embrace the mission of protecting public health

- 7. Accelerate technology adoption to build efficiency and improve water service

Each of these policy briefs digs further into one of these big ideas—exploring the key issues behind it; presenting policy solutions that are working at the local, regional, state, and national levels; and providing real world examples of how these solutions are being implemented and do produce positive results.

The One Water for America Policy Framework is a clarion call to action to accelerate solutions for the water management problems of our age. In doing so, we secure a brighter future for all.

Context

The challenge of lead in our drinking water was raised at every one of the One Water for America Listening Sessions. This is a reflection of national attention that started with the Flint water crisis and then began spreading across the nation, as more cities have grown aware of their own lead-in-water problems.

When anyone turns on a tap in their home, school, or place of business, the water from the tap should be safe to drink. Water utilities are responsible for providing safe drinking water by treating water to regulatory standards, and by maintaining safe water quality through the distribution system. However, there are limits to water utilities’ ability to assure safe water at the tap, since water utilities do not control the quality of plumbing systems within individual property lines. If communities are committed to providing safe drinking water, while water utilities can lead the charge, we must reach across silos to generate community wide solutions that engage healthcare systems, school systems, community groups, city and county departments, and state agencies.

It is important to acknowledge that lead is just one of the water quality challenges that communities must address to protect public health. As ever, communities and utilities must balance limited resources across a broad set of priorities. While lead today receives a great deal of attention, each community faces its own array of challenges, and local prioritization of resources is important. In addition, water utilities alone cannot solve pressing problems like lead in tap water, arsenic in groundwater, or pharmaceuticals in water supplies. But the water sector can be a leader in collaborative efforts to define solutions, motivated by the imperative of public health protection.

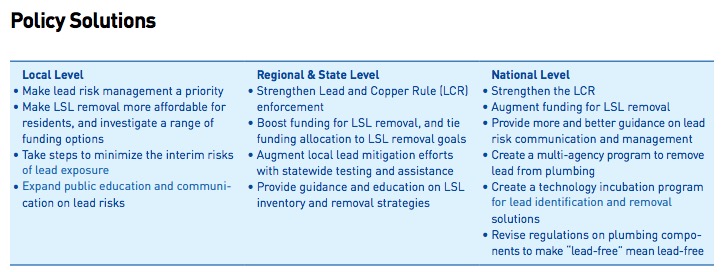

In this policy brief we review key issues influencing leadin-water risks, followed by recommended policy solutions and case studies at the local, regional, state, and national levels.

Key issue: Education and public awareness

Lead is a neurotoxin, and there is no known level of lead exposure that is considered safe for humans.1 Even low levels of lead in children’s bloodstreams can cause significant, lifelong adverse effects on intelligence, behavior, and overall life achievement. 2 Since lead exposure causes serious health effects and has high social costs, there is broad consensus that our drinking water systems and plumbing should be lead-free. Yet, lead-in-water is a legacy issue that reaches across private property lines and different agencies’ areas of responsibility, presenting unique challenges from one place to the next. In our listening sessions, we heard that lead is a particularly acute problem because it raises the fundamental issue of trust in those who manage and oversee our water systems. In the wake of the Flint water crisis, elevated lead levels continue to be found in communities across the US, yet generally there is little education on the risks, and little public awareness of how to manage them. Questions remain on lead removal: Who is responsible for it, who will pay for it, and how should it be done? And, in the interim, what should we be doing to mitigate the risk of exposure? Solutions will require extensive work on education and awareness, multi-level policy change, and cross-agency collaboration.

Key Issue: Regulations—and enforcement—to minimize lead risks

The federal government began to more fully address and reduce the use of lead in plumbing systems in 1986. While limited amounts of lead are still allowed in some plumbing components, much of the lead remaining in our water systems is in lead service lines (LSLs)—the pipes that connect individual properties to the water main in the street—and in older in-home plumbing. Across the nation, there are an estimated six million to ten million LSLs still in place. The actual number is unknown, because many water utilities do not know how many LSLs exist in their communities, and many homeowners have no records of them. Under EPA’s direction, states say they are implementing plans to complete service line inventories as required under federal law.

In 1991, EPA published the federal Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) under the Safe Drinking Water Act to protect consumers from lead in drinking water. Under the LCR, many water systems established best practices for corrosion control treatment to reduce the release of lead in water distribution systems, but questions remain about whether the LCR does enough to protect public health. For example, lead testing is voluntary for most schools and daycares, even though lead affects children most profoundly. EPA is revising the LCR to improve and streamline public health protection. The National Drinking Water Advisory Council (NDWAC) recommended substantial changes to the LCR, including proactive and carefully managed LSL replacement, more robust public education, a commitment to corrosion control based on the latest sound science, and modified monitoring and testing. However, some feel that more is needed, especially around sampling and communication protocols.

LCR enforcement is also a concern. The LCR’s testing guidelines are applied differently from one community, and one state, to the next. EPA data shows that more than 5,300 water systems in the US, serving nearly 18 million people, have been found in violation of the LCR, yet state and federal regulators took enforcement action in less than 1,000 of those cases. A key issue is compliance with monitoring and sampling requirements, because some communities use methods that can underrepresent the extent of lead release problems.

Key Issue: Funding and logistics for lead removal

Removing lead pipes from our water systems is the best way water utilities and communities can reduce the risk of lead in drinking water. A recent study estimates that nationwide, removing LSLs from the homes of children born in 2018 would yield $2.7 billion in future benefits, or about $1.33 per dollar invested.

Fully removing lead service lines is complicated—it requires accessing private property (with attendant questions of liability), and can be expensive, estimated at $5,000 to $7,500 per service line. There are questions in every community about who should bear those costs, and investing in lead removal means reallocating resources from other high-priority needs. Because of these challenges, many water utilities that do tackle LSLs have been replacing only the part of the service line that is in the public right-of-way—but the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has linked partial LSL replacement to increases in blood lead levels. Full LSL replacement requires more collaboration with property owners, some of whom may be skeptical of the effort if it is not fully understood.

As we consider approaches for removing LSLs, we must ensure that they are affordable and implementable for all. Relying on all customers to plan, fund, and implement their own lead mitigation projects will not work. And because solving lead problems will take time (possibly decades), communities need to act in the near term to manage the risks of lead exposure during everyday operations, maintenance, and construction work.

Key Issue: In-building plumbing and lead

The presence of lead in water systems goes beyond the service line and exists in plumbing systems. The use of lead in pipes and solder was banned under the Safe Drinking Water Act Amendments of 1986, but lead may be present in the plumbing systems of homes, apartment buildings, schools, park facilities, daycare centers, and other structures built before the ban. Some lead content is still allowed in plumbing components, although the permissible amount was reduced in 2014. The problem of lead in in-building plumbing is particularly acute in historically underserved communities, where housing may be dilapidated, and the effects of all sources of lead exposure— from water systems and in-home plumbing, but also paint, contaminated soil, and air—may compound the problem.

Key Issue: Limitations of corrosion control

Because of the challenges involved in removing all sources of lead from plumbing systems, many water utilities have relied on corrosion control since the 1991 LCR as the primary means of controlling lead exposure in public water systems. Corrosion control strategies involve adding chemicals to treated drinking water to form a protective coating, or scale, inside pipes in the distribution system. This scale, if uninterrupted and stable, reduces the release of lead from pipes and solder into the water. While corrosion control has provided a great deal of protection from lead risks, it has its limitations. Even with effective corrosion control, disturbing a LSL—for example, by partially replacing it, or working on a connected water main, or installing a new water meter—can sometimes result in elevated lead levels at the tap for weeks, and even months, after the disturbance occurs. In addition, low or intermittent use of water in a household in some cases can increase the likelihood of lead in tap water, even in systems with effective corrosion control.

Download full version (PDF): Reduce lead risks, and embrace the mission of protecting public health

About the US Water Alliance

uswateralliance.org

“The US Water Alliance is driving a one water movement. We envision a future where all water is valued. Irrigation on a farm. Water from the tap. Stormwater. Water flowing toward a treatment plant. Water, in all its forms, is valuable, and our collective future depends on water. At the US Water Alliance, we are transforming the way the nation values and manages our most precious resource.”

Tags: Lead, Lead contamination, One Water for America, US Water Alliance, Water, Water Infrastructure

RSS Feed

RSS Feed