RAND CORPORATION

Summary and Recommendations

Infrastructure has become a popular topic, fueled by a widely held perception among the general public and many elected officials that the nation’s infrastructure is crumbling as a consequence of age and underinvestment. In fact, not all transportation and water infrastructure in the United States is falling apart—far from it. While highway, bridge, and water system maintenance backlogs exist in many places, the data do not support a picture of precipitous decline in total national spending or in the condition of the assets. Rather, the U.S. infrastructure story is far more nuanced and challenging.

The purpose of infrastructure is to improve worker and business productivity and social welfare. Money alone will not accomplish this goal; policy changes will also be required. Large infusions of direct federal spending or tax credits to repair or build anew may do some good by stimulating demand for construction services—even if the projects do not advance longterm priorities or address differing needs across the country. The federal government should focus its policies on incentivizing increased public and private spending on maintenance and modernization where it is needed.

The purpose of infrastructure is to improve worker and business productivity and social welfare. Money alone will not accomplish this goal; policy changes will also be required. Large infusions of direct federal spending or tax credits to repair or build anew may do some good by stimulating demand for construction services—even if the projects do not advance longterm priorities or address differing needs across the country. The federal government should focus its policies on incentivizing increased public and private spending on maintenance and modernization where it is needed.

But increased spending will not fix what is broken in our approach to funding and financing public works—and not everything is broken. State and local governments are in the best position to make needed improvements in the way struggling public transit and most other infrastructure systems are governed. But the federal government has a role to play in more ambitious regional initiatives to benefit the nation as a whole. Understanding the particulars of where help and resources are needed should guide Congress, states, and cities in their deliberations on policy changes, tax changes, and budgeting.

Core to understanding the problem is knowing who or what is responsible for a failure to meet demand for improved infrastructure services. While the federal government has historically played a large role at times, state and local governments shoulder the majority of the burden. In 2014, state and local governments accounted for 62 percent of capital expenditures and 88 percent of operations and maintenance (O&M) spending for transportation and water infrastructure (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], 2015). While transportation and water infrastructure are rarely considered together from a policy perspective, these two large infrastructure sectors share characteristics that are particularly relevant in today’s policy debate: dominant public ownership, extensive use of tax-exempt financing, and a tangled web of federal involvement.1 These patterns stand in marked contrast to the energy, telecommunications, aviation, and freight rail sectors, which are dominated by private firms. In this report, we identify the policies that promote and deter sustainment of and investment in U.S. transportation and water infrastructure and suggest steps to better align them to public priorities.

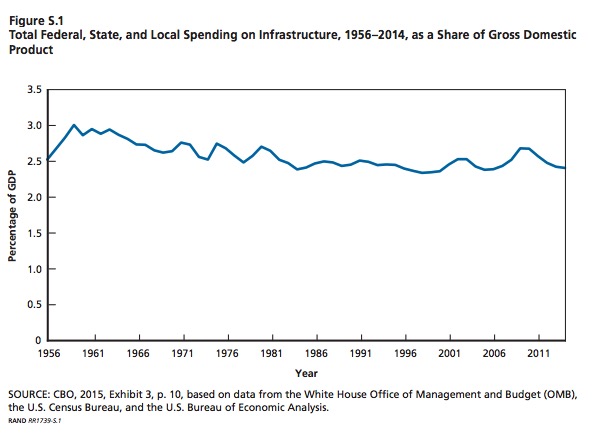

Over the past 60 years, public spending on infrastructure has generally tracked the growth of the U.S. economy. Total public spending on infrastructure as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), normalized in 2014 dollars, has been relatively stable since 1956, as shown in Figure S.1. Whether spending levels are adequate depends on the specifics.

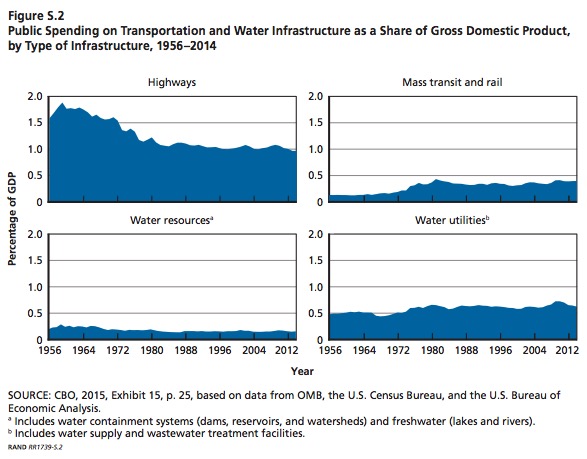

Between 1964 and 1980, total public spending on highways decreased as a percentage of GDP and has been relatively flat since then. Spending on mass transit, rail, water resources, and water utilities as a percentage of GDP increased or remained relatively flat between 1980 and 2014, as shown in Figure S.2. Federal capital spending on highways has been declining for decades since the building of the Interstate Highway System in the 1950s and 1960s, even as total vehicle-miles traveled has been increasing. For both transportation and water infrastructure, total public spending and spending per capita generally rose until the 2008 financial crisis, and there is ample evidence that spending has picked up again in many places. By the end of 2016, municipal bond issues were at their highest levels ever, more than doubled from 1996; however, uncertainty in federal policy has driven bond issues down in 2017. Industry analysts project that spending in the water and wastewater utility sector alone will exceed $532 billion over the next ten years, a 28 percent increase over the previous decade (Nabers, 2016). If this new spending materializes at a rate of around 2.5 percent annually above inflation, the spending shortfalls in the water sector projected by the American Society of Civil Engineers (2013) and others would largely disappear. The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) projected that increasing spending on highways and bridges by around 2.8 percent annually above inflation through 2032 would eliminate the projected maintenance backlog (DOT, Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, 2016).

In fact, the perception that U.S. infrastructure needs are not being met, which animates so much of the debate over spending, requires reexamination. These “needs gaps” are calculated in different ways. For water infrastructure, some needs are derived from estimates of repair frequency required to maintain a regulatory standard, given factors such as population growth and age of the system. Other estimates use survey data to collect information on self-reported costs of planned future projects. The adequacy of pricing and cost-recovery methods across state and local governments can alter the view of needs as well. The bottom line is that needs assessments offer an unreliable guide for policy and priority setting.

In fact, the perception that U.S. infrastructure needs are not being met, which animates so much of the debate over spending, requires reexamination. These “needs gaps” are calculated in different ways. For water infrastructure, some needs are derived from estimates of repair frequency required to maintain a regulatory standard, given factors such as population growth and age of the system. Other estimates use survey data to collect information on self-reported costs of planned future projects. The adequacy of pricing and cost-recovery methods across state and local governments can alter the view of needs as well. The bottom line is that needs assessments offer an unreliable guide for policy and priority setting.

State and local O&M spending for both highways and water infrastructure has risen steadily since at least 1956. The system of financing new and major rehabilitation projects through public borrowing and, to a much lesser extent, some version of public-private partnerships (PPPs) is generally working for projects that fall within single states and local jurisdictions and for which revenues are sufficient to cover debt service and ongoing O&M costs. Infrastructure tends to be well maintained and modernized in areas where local and regional economies are thriving, good governance is the rule, and revenue streams for sustainable O&M cost recovery are in place.

Elsewhere, problems persist that defy easy solutions:

- The federal Highway Trust Fund and the state funds for drinking water and wastewater treatment plants have not been operating on a sustainable basis for some time now.

- Congestion on some interstate highways and freight transportation systems hurts regional economies.

- Without operating subsidies, mass transit systems have a hard time paying their way.

- Critical infrastructure problems that cross jurisdictional lines, like the proposed Gateway rail tunnel under the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York, are proving difficult to resolve through existing governance arrangements.

- Communities with declining tax bases struggle to maintain their roads, bridges, and water systems and repay their debts to bond holders.

- Some communities are at risk of flooding from structurally compromised dams and levees, coastal communities are at risk from rising seas and changing patterns of precipitation, and many communities are vulnerable to flooding from undersized and aging storm water systems.

Each place has its own blend of issues with infrastructure maintenance or investment, economics or governance. Dysfunction arises from many sources. An across-the-board rampup of federal spending is unlikely to solve the infrastructure problems that need fixing— regardless of whether the money comes through direct funding, tax credits to private developers, or a combination. Lasting changes will require thoughtful consideration of targeted spending priorities, policy constraints, and regional differences.

Though state and local governments are responsible for many pieces of this mosaic, Congress could take a number of steps in conjunction with states, local governments, and the private sector to improve the condition, funding, and sustainability of U.S. infrastructure (see text box).

To maintain stable financing for infrastructure, Congress should preserve the federal tax exemption on interest earned from municipal bonds for at least the next decade. During this period, lawmakers should reinstate taxable Build America Bonds (BABs) and experiment with other financing alternatives. The aim is to draw as much capital into infrastructure as the market demands without the distortion of tax policies that favor one class of investors over another.

Tax-exempt municipal bonds are an inefficient means of subsidizing local government borrowing for infrastructure projects. Still, the $3.7 trillion market for these bonds provides stable financing to local governments. In the interest of continuity, tax-exempt municipal bonds should be kept while alternative funding mechanisms are given a chance to develop. Congress successfully experimented with BABs in 2009 and 2010. These offer one potential alternative. BABs can be structured to be revenue-neutral. Public pension funds and other investor classes receive no benefit from municipal bonds’ tax exemption because they have either no or low tax liabilities. But BABs would allow their “patient” capital to be put to work funding low-risk infrastructure projects with long payback periods and competitive returns.

Therefore, BABs should be reinstated for a ten-year period with the assurance that the subsidy, at whatever level set by Congress, will be honored over the life of the bonds. At the end of the ten-year period, Congress should assess the impacts on state and local infrastructure spending and the federal budget and determine whether to maintain the status quo, make BABs permanent, or cap or eliminate the municipal bond exemption.

Ten Recommendations to Congress on Infrastructure

Tax-Exempt Bonds

Preserve the federal tax exemption on interest earned from municipal bonds for at least the next decade. Tax-exempt municipal bonds are needed to give state and local governments continued stable access to capital while alternative financing mechanisms are developed.

Taxable Bonds

Reinstate Build America Bonds with taxable interest for a ten-year period and experiment with other financing alternatives. Draw as much capital into infrastructure as the market demands without the distortion of tax policies that favor one class of investors over another.

Sustainable Revenues for Transportation

Support further state experimentation with approaches to mileage-based fee collection, with an eye toward transitioning to a new federal system that more effectively links revenue collection to highway use.

Long-Term Priorities

Target longer-term projects likely to produce significant national benefits. Fund transportation and water improvements that will increase productivity and resilience over merely “shovel-ready” projects.

Capital

Focus on capital investment, including major investments in renewal of aging infrastructure and new infrastructure incorporating advanced technologies. Make life-cycle cost analysis and sustainability of investments through appropriate pricing and cost recovery a condition of future federal transportation and water funding for state and local governments.

Maintenance

Prioritize maintenance of federal assets, such as mission-critical military bases, dams, levees, locks, national parks, and other vital federal infrastructure.

Resilience

Make resilience to natural disasters and adaptation to rising seas, increasing flood frequency, and other changing climate impacts a condition for capital spending for the purpose of reducing future federal spending on disaster assistance.

Efficiency

Streamline the regulatory review process among multiple federal agencies. Efficiencies can be gained while honoring environmental and safety standards.

More Efficiency

Consolidate the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation into an integrated national water resource agency.

Innovation

Fund competitive grants for research, development, and deployment of new technologies. Expand existing grant programs to stimulate innovation in engineering, construction, maintenance, and operations of transportation and water systems.

Download full version (PDF): Not Everything Is Broken

About RAND Corporation

www.rand.org

The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous.

Tags: Infrastructure Financing, RAND Corporation, Tax Recommendations, Tax reform, Transportation Infrastructure, Water Infrastructure

RSS Feed

RSS Feed