ASSEMBLY MINORITY TASK FORCE ON CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE & TRANSPORTATION

Executive Summary

Transportation infrastructure is an integral part of New York State, connecting 19.85 million New Yorkers to the 47,126 square miles of land we call home. Every day, New Yorkers depend on reliable transportation infrastructure to seek opportunities, to access healthcare, and to receive education. Effective and safe transportation infrastructure is also vital to New York’s economy, allowing businesses to operate, goods and services to move freely, and workers to access current jobs and new prospects. Each year, transportation infrastructure allows more than $1 trillion in goods to be shipped to and from the state. What’s more, not only does transportation infrastructure play a leading role in maintaining a vibrant and robust economy, investment in this sector pays dividends. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) estimates that for every $1 spent on road, highway, and bridge improvements, there is an average benefit of $5.20 yielded from reduced congestion, lower vehicle maintenance costs, and lower road and bridge maintenance costs. In places not easily accessible to public transportation, people especially rely on roads and bridges to achieve a good quality of life.

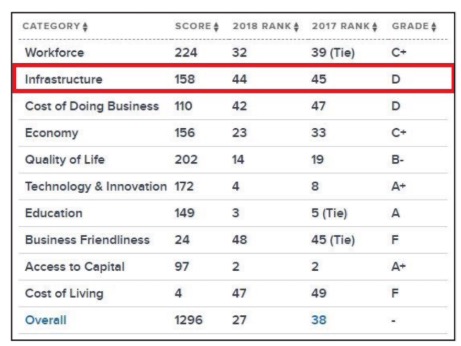

Because of the clear importance of safe and dependable transportation infrastructure, every New Yorker should be concerned about the current condition of the state’s roads and bridges. CNBC’s 2018 study, Top States for Business, ranked New York’s infrastructure as 7th worst in the country due to the poor state of road, bridge, and water system conditions.

According to a 2016 report from TRIP, a national transportation research group, deficient roads cost New Yorkers $24.9 billion a year in vehicle operating costs, congestion-related delays, and traffic crashes. New Yorkers also have the longest commutes of any state in the country, averaging 32.6 minutes each way. In 2017, John J. Shufon noted in his report, Road to Ruin, the backlog of repair work for the 15,097 centerline highway miles owned by the state was estimated at $5.5 billion, up from $4.3 billion just two years prior. This is especially troubling because the state’s share of highway ownership is only a fraction of that owned by local governments. Local governments own more than 97,000 centerline highway miles and, due to funding constraints, these highways are often in worse condition than those owned by the state. Unfortunately, bridges in the state are in a similar state of crisis. In 2017, the Office of the State Comptroller (OSC) sounded the alarm on the deteriorating condition of local bridges, citing a cost of $27.4 billion needed to repair 8,834 bridges owned by local governments. Repairing all 17,456 bridges in New York State is estimated to cost a staggering $75.4 billion. Furthermore, the federal government classifies 10.5 percent of New York’s bridges as structurally deficient, the 10th most of this type in the country. Statewide, 91 bridges are currently closed, leading to longer commutes and increased difficulty accessing basic necessities including healthcare and education.

While the need is clear and great, securing adequate funding for transportation infrastructure is a never-ending battle. The Dedicated Highway and Bridge Trust Fund (DHBTF), the state’s primary transportation infrastructure funding mechanism, has been heavily scrutinized in recent years for its inability to adequately fund capital investments. Since 2005, OSC has issued three separate reports analyzing the DHBTF, most recently projecting that in SFY 2018-19 capital spending would comprise only 19.2 percent of disbursements with debt service costs comprising 42.2 percent and state operations costs comprising the other 38.6 percent. Federal funding has also faltered, in large part due to policy surrounding the no longer effective Highway Trust Fund (HTF)—the main source of funding for federal investments in road, bridge, and transit infrastructure. Approximately 90 percent of the HTF is funded through the motor fuels tax, which taxes gasoline at a rate of 18.3 cents per gallon and diesel fuel at a rate of 24.3 cents per gallon. However, this tax rate has not increased since 1993, and as a result has 40 percent less purchasing power than it did in that year.

These issues have jeopardized the physical and financial health of New Yorkers, and to ensure the state’s roads, bridges, and critical infrastructure remain safe and reliable, this past fall, the Assembly Minority Task Force on Critical Infrastructure and Transportation held eight forums throughout the state to listen to local officials, highway superintendents, first responders, affected drivers, and business owners about their firsthand experiences. Task force Co-Chairmen Assemblymen Phil Palmesano and Kevin Byrne traveled the state to listen to transportation and critical infrastructure concerns to help develop solutions that safeguard our infrastructure assets and keep our residents and businesses moving freely and safely across the state.

These issues have jeopardized the physical and financial health of New Yorkers, and to ensure the state’s roads, bridges, and critical infrastructure remain safe and reliable, this past fall, the Assembly Minority Task Force on Critical Infrastructure and Transportation held eight forums throughout the state to listen to local officials, highway superintendents, first responders, affected drivers, and business owners about their firsthand experiences. Task force Co-Chairmen Assemblymen Phil Palmesano and Kevin Byrne traveled the state to listen to transportation and critical infrastructure concerns to help develop solutions that safeguard our infrastructure assets and keep our residents and businesses moving freely and safely across the state.

Testimony provided at the forums confirmed that efforts to fix New York’s transportation infrastructure depend on cooperation and commitment from every level of government, from village departments of public works up to the FHWA. Although the average driver may not discern a physical difference when driving over a state-or locally-owned road or bridge, the priorities, resources, and strategies that construct and maintain these roads can differ greatly. To reverse the trend of infrastructure deterioration, cooperation and communication between all levels of government must be open and proactive. Most stakeholders spoke favorably of the working relationships with the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT), illustrating that the genesis of the transportation and critical infrastructure crisis lies not with those doing the work, but rather with the planning, funding, and policies that dictate work.

One sentiment was echoed unanimously at every forum; there is a crucial need for the state to forge a stronger partnership with municipalities and provide more robust and more consistent funding for local road, bridge, and water infrastructure. Nearly nine out of every 10 roads in the state are maintained under local jurisdiction, totaling more than 97,000 centerline miles owned by local governments (as compared to just over 15,000 lane miles owned by the State).11 Additionally, of the 17,462 bridges in the state, half, or 8,834, are owned by local governments. Funding for local critical and transportation infrastructure was the most prevalent issue raised during the course of the forums. New York State, like many states across the country, is struggling to provide an adequate investment to maintain and improve its infrastructure assets. This was expressed by those who are on the ground, stretching budgets, searching for cost- saving techniques, and sounding the alarm about how past and present funding simply has not kept up with the extent of need. Mayors, engineers, department of public works (DPW) supervisors, and highway superintendents all shared stories about the difficulties of protecting such expensive and

important assets with increasingly tight budgets that often make it difficult to simply maintain their systems, much less improve them. One highway superintendent stated, “We’re just keeping our heads above water.” All municipalities across the state rely on Consolidated Local Street and Highway Improvement Program (CHIPS) funding to carry out maintenance and rehabilitation projects, and for some, it is the sole source of their paving budget. The yearly CHIPS base funding has only increased $75 million in the past 10 years—from $363 million in SFY 2008-09 to $438 million in SFY 2018-19— and the rising costs of construction labor, materials, and state-mandated rules and regulations have prevented localities from getting ahead. New programs included in the 2015-20 NYSDOT Capital Program, such as PAVE-NY and BRIDGE NY, have largely been seen as welcome and successful programs that localities now rely on as part of their infrastructure funding. In addition to ensuring that these programs are part of the next NYSDOT Capital Program, increasing funding for CHIPS, water and sewer, and culverts will be vitally important in the continuing fight to safeguard infrastructure assets. In order to accomplish this goal, it should be understood that achieving parity between the next NYSDOT and Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Capital Programs is a necessity. The MTA is a vital transportation asset and its importance to New York City and the New York Metropolitan area cannot be understated. However, just as the MTA serves so many downstate residents, the network of local- and state-owned roads and bridges is equally as important to residents and businesses across the state, particularly upstate. To safeguard these systems, parity must be achieved.

Although the funding that Regional DOTs, highway superintendents, and DPWs have at their disposal is already limited, an increasingly complex web of rules and regulations has further eroded their ability to complete projects. Securing funding is an arduous task, and the number of rules and regulations that must be complied with often eat substantially into budgets meant for much-needed construction. Compliance with these rules and regulations is costly and can delay projects by months, even years. Procedures for Locally Administered Federal Aid Projects guidelines, prevailing wage rates, Americans with Disabilities Act compliance, Minority- and Women-Owned Business Enterprise Program requirements, Department of Environmental Conservation regulations, and BRIDGE NY application processes were all cited as issues that localities have trouble complying with in a timely and cost effective manner. As municipalities are facing the difficulty of meeting the ever growing list of needs with stagnant budgets, rules and regulations need to be assessed for their viability, necessity, and ability to benefit those the projects are intended to serve. The excessive number and undue complexity of many of these rules and regulations have proven, in many cases, to hamper the success of projects rather than add to them.

Although the funding that Regional DOTs, highway superintendents, and DPWs have at their disposal is already limited, an increasingly complex web of rules and regulations has further eroded their ability to complete projects. Securing funding is an arduous task, and the number of rules and regulations that must be complied with often eat substantially into budgets meant for much-needed construction. Compliance with these rules and regulations is costly and can delay projects by months, even years. Procedures for Locally Administered Federal Aid Projects guidelines, prevailing wage rates, Americans with Disabilities Act compliance, Minority- and Women-Owned Business Enterprise Program requirements, Department of Environmental Conservation regulations, and BRIDGE NY application processes were all cited as issues that localities have trouble complying with in a timely and cost effective manner. As municipalities are facing the difficulty of meeting the ever growing list of needs with stagnant budgets, rules and regulations need to be assessed for their viability, necessity, and ability to benefit those the projects are intended to serve. The excessive number and undue complexity of many of these rules and regulations have proven, in many cases, to hamper the success of projects rather than add to them.

The status of water and sewer infrastructure was also brought up by officials throughout the forums. Although these infrastructure assets are less visible than the state’s roads and bridges, their value and importance to communities and businesses is no less. Throughout the forums, participants spoke about the necessity of investing in systems that are desperately in need, especially older systems. For example, at one forum, an engineer noted the city’s sewer system was built largely before 1940. Others discussed water infrastructure consisting of clay pipes and materials containing asbestos, and while not currently dangerous, they clearly indicate how antiquated our water and sewer infrastructure is in some areas. Additionally, participants expressed concerns about water and sewer infrastructure quality having the ability to either attract or repel businesses. For many municipalities across the state, the present condition of these assets has become yet another deterrent to attracting businesses, thereby hampering the economic viability of the immediate area. Throughout the forums, many were proponents of using a CHIPS-like formula to help ensure localities have the requisite funding to repair and upgrade these assets.

Finally, long-range planning was also seen as a crucial component to rebuilding our critical and transportation infrastructure. New York State currently lacks a long-term strategic vision for its transportation infrastructure, due in large part to a disregard for long-range planning. To this point, the state’s last strategic plan was released in 2006, and has not been revised or updated in the 13 years since. Beyond long-range planning, the current NYSDOT Capital Program process ignores best practices and has been influenced by past legislative negotiations rather than focusing on the state’s infrastructure needs. New Yorkers deserve a capital program and long-range plan that are transparent, as well as need- and data-based. The future economic and social ramifications are too great to allow the state’s continued failure to create and execute a strategic vision.

Download full version (PDF): New York’s Infrastructure

Tags: New York, New York Infrastructure, NY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed