METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM

BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

Background

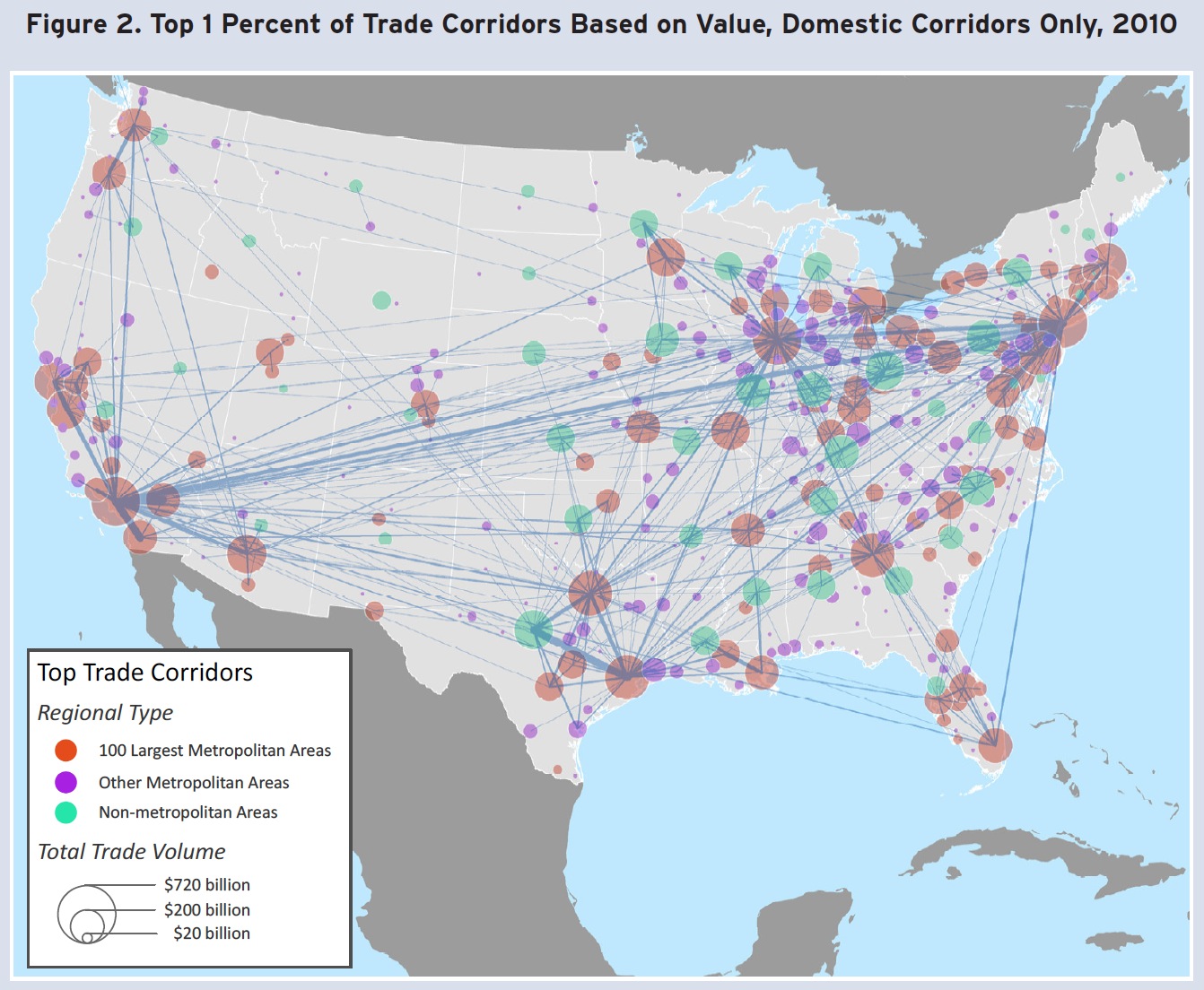

Each year, the United States moves over $20 trillion in goods weighing over 17 billion tons between hundreds of metropolitan, non-metropolitan, and international regions. It does so using an extensive network of freight assets: over 4 million miles of highways, local roads, railways, navigable waterways, and pipelines; hundreds of seaports and airports; and thousands of intermodal facilities to tie the network together. Without this network, it would be impossible for regional economies to trade goods and reach their full economic potential.

Managing this network rests on the shoulders of both the public and private sectors, which share various responsibilities in planning and policy development. The public sector owns and operates assets like airports and interstate highways, while also regulating local land use and national safety standards. In contrast, the private sector operates vehicles and other equipment to move goods, while owning distribution centers and other freight assets such as rail lines.

Today, this public-private relationship is at a critical juncture. From the federal to the local level, freight policy has frequently fallen short with its private sector partners, moving forward without a central purpose or set of clearly defined economic priorities.7 As a consequence, metropolitan economies—and the firms located within them—may increasingly be at a competitive disadvantage with their global peers.

Federally, the national strategy is outdated and overly stovepiped. National transportation policy focuses on connectivity, epitomized through the National Highway Trust Fund’s effort to build the interstate highway system and forge physical bonds across the country. In many ways, that investment has proven a great success, but it treats every state and metropolitan area as relatively equal traders within the larger national system. To make matters worse, there is no dedicated freight investment program designed to support the country’s multimodal freight network. National trade policy also provides little clarity concerning freight, concentrating instead on international agreements and where goods enter or exit the country. This approach ignores domestic trade between metropolitan areas and, in particular, the supply chains that connect metro areas to one another and to U.S. ports.

Freight strategies have also frequently been lacking at the state and local levels. Although states physically built the national highway system by connecting major population centers to one another and to rural production hubs, many did not necessarily prioritize maintenance or new capacity around specific economic criteria once the original system was complete. Meanwhile, metropolitan policies continue to focus on personal transportation needs, such as commute times, and often overlook the freight demands of tradable industries. This leaves goods-trading and logistics firms to cover the costs of an inefficiently planned network, such as continued bottlenecks in key trading corridors or outdated technology like radar-based aviation.

As a result, public and private leaders have not only struggled to develop freight strategies that are responsive to national concerns, but they have also failed to tailor these policies at a local level—a serious shortcoming given the central role of metropolitan economies.

Indeed, the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas serve as its primary consumers of raw commodities, its biggest producers of manufactured goods, and its leading exporters and importers.12 Moreover, their specialization in advanced industrial (AI) commodities like precision instruments, pharmaceuticals, and electronics is central to the national economy, driving future production and innovation.13 Metropolitan areas forge strong connections with each other—both within and beyond the country’s borders—to develop unique industrial specialties and power regional output.14 This connectivity strengthens the metropolitan presence in global value chains and leads to long-term economic gains through globally coordinated goods production, consumption, and distribution.15

To coordinate freight strategies more effectively, it is critical that policymakers understand how trade works at the subnational scale. Mapping trade networks—assessing exactly who trades with one another, in what amounts, and in which commodities—can not only help guide future planning efforts and investment strategies at the national, state, and local levels, but can also clarify specific trade corridors and gateways across the country. Analyzing networks at the metropolitan level can also help leaders better understand how certain economic indicators—like industrial output and employment—drive trade among specific regions. Ultimately, with a more thorough awareness of how these networks function, leaders can start to craft improved, targeted transportation policies that support the physical movement of goods and advance long-term economic goals.

Through a variety of statistical measures, this report explores how network data can help metropolitan areas better understand their place in goods trade and inform the development of comprehensive freight strategies nationally. After briefly discussing the research methodology, the report describes the concentration of the nation’s goods trade network along specific trade corridors and between specific metropolitan areas. It then examines regional trade connections in the domestic and international marketplace, judging these trade levels based on several economic factors, including output and employment. The report also reveals the highly interconnected nature of this metropolitan network across state lines, revealing the need for a coordinated approach. Finally, the report concludes with a discussion of implications for freight policy throughout a federalist system.

Download full version (PDF): Mapping Freight

About the Brookings Institution

www.brookings.edu

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, DC. Our mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations that advance three broad goals: Strengthen American democracy; Foster the economic and social welfare, security and opportunity of all Americans; and Secure a more open, safe, prosperous and cooperative international system. Brookings is proud to be consistently ranked as the most influential, most quoted and most trusted think tank.

Tags: Brookings Institution, Freight, Global Cities Initiative, Metropolitan Policy Program

RSS Feed

RSS Feed