US GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE

What GAO Found

Over the years, the federal-aid highway program has expanded to encompass broader goals, more responsibilities, and a variety of approaches. As the program grew more complex, the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) oversight role also expanded, while its resources have not kept pace. As GAO has reported, this growth occurred without a well-defined overall vision of evident national interests and the federal role in achieving them. GAO has recommended Congress consider restructuring federal surface transportation programs, and for this and other reasons, funding surface transportation remains on GAO’s high- risk list.

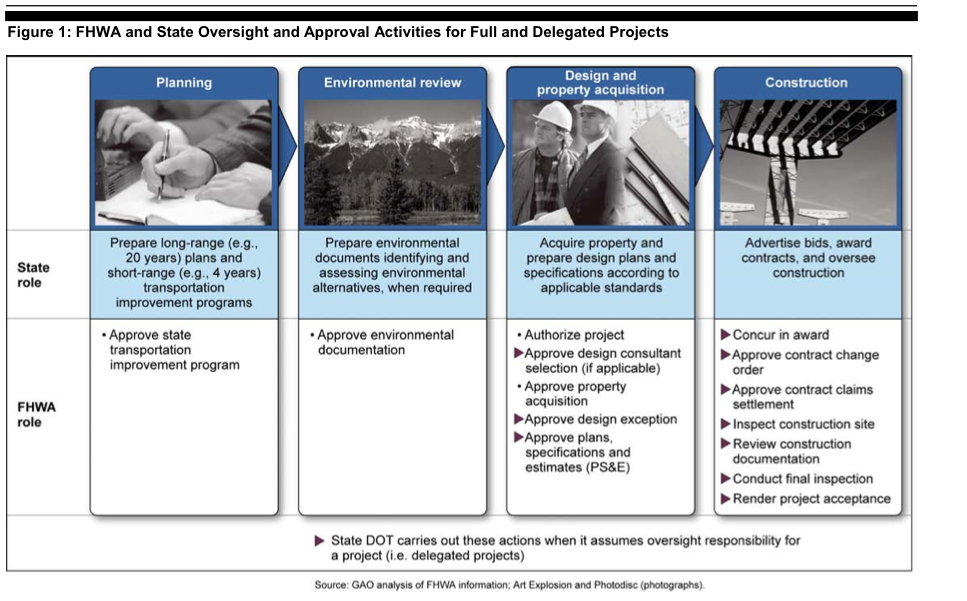

FHWA benefits from using recognized partnership practices to advance the federal-aid highway program and conduct program oversight—such as clear delineation of roles and responsibilities between FHWA and its state partners and formal and informal conflict resolution—that are recognized as leading practices. FHWA’s partnership approach allows it to proactively identify issues before they become problems, achieve cost savings, and gain states’ commitment to improve their processes.

FHWA’s partnership approach also poses risks. We observed cases where FHWA was lax in its oversight or reluctant to take corrective action to bring states back into compliance with federal requirements, potentially resulting in improper or ineffective use of federal funds. For example, while FHWA has made it a national priority to recoup funds from inactive highway projects—projects that have not expended funds for over 1 year—FHWA officials in three states we visited were reluctant to do so because of concerns about harming their partnership with the state. In other cases, FHWA has shown a lack of independence in decisions, putting its partners’ interests above federal interests. For example, FHWA allowed two states to retain unused emergency relief allocations to fund new emergencies, despite FHWA’s policy that these funds are made available to other states with potentially higher-priority emergencies. In some instances, FHWA became actively and closely involved in implementing solutions to state problems—this can create a conflict when FHWA later must approve or review the effectiveness of those solutions.

If proposals for a performance-based highway program are adopted, FHWA would have to work with states to develop measures and take corrective action if states do not meet them. FHWA’s partnership could help states develop measures, but it would need to mitigate the risks posed by its partnership to ensure corrective action was effective when needed. The fundamental reexamination of surface transportation programs, including the highway program, that GAO previously recommended presents an opportunity to narrow FHWA’s responsibilities so that it is better equipped to transition to a performance-based system. GAO identified areas where national interests may be less evident but where FHWA expends considerable time and resources— areas where devolving responsibilities to the states may be appropriate.

About the GAO

www.gao.gov

“The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress. Often called the “congressional watchdog,” GAO investigates how the federal government spends taxpayer dollars. The head of GAO, the Comptroller General of the United States, is appointed to a 15-year term by the President from a slate of candidates Congress proposes. Gene L. Dodaro became the eighth Comptroller General of the United States and head of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) on December 22, 2010, when he was confirmed by the United States Senate. He was nominated by President Obama in September of 2010 and had been serving as Acting Comptroller General since March of 2008.”

Tags: Federal Highway Administration, FHWA, GAO, US Government Accountability Office

RSS Feed

RSS Feed