FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO

Increasing government spending during periods of economic weakness to offset slower private-sector spending has long been an important policy tool. In particular, during the recent recession and slow recovery, federal officials put in place fiscal measures, including increased government spending, to boost economic growth and lower unemployment. One form of government spending that has received a lot of attention is public investment in infrastructure projects. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) allocated $40 billion to the Department of Transportation for spending on the nation’s roads and other public infrastructure. Such public infrastructure investment harks back to the Great Depression, when programs such as the Works Progress Administration and the Tennessee Valley Authority were inaugurated.

Increasing government spending during periods of economic weakness to offset slower private-sector spending has long been an important policy tool. In particular, during the recent recession and slow recovery, federal officials put in place fiscal measures, including increased government spending, to boost economic growth and lower unemployment. One form of government spending that has received a lot of attention is public investment in infrastructure projects. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) allocated $40 billion to the Department of Transportation for spending on the nation’s roads and other public infrastructure. Such public infrastructure investment harks back to the Great Depression, when programs such as the Works Progress Administration and the Tennessee Valley Authority were inaugurated.

One criticism of public infrastructure programs is that they take a long time to put in place and therefore are unlikely to be effective quickly enough to alleviate economic downturns. The fact is, though, that surprisingly little empirical information is available about the effect of public infrastructure investment on economic activity over the short and medium term.

This Economic Letter examines new research (Leduc and Wilson, forthcoming) on the dynamic effects of public investment in roads and highways on gross state product (GSP), the total economic output of a state. This research focuses on investment in roads and highways in part because it is the largest component of public infrastructure in the United States. Moreover, the procedures by which federal highway grants are distributed to states help us identify more precisely how transportation spending affects economic activity.

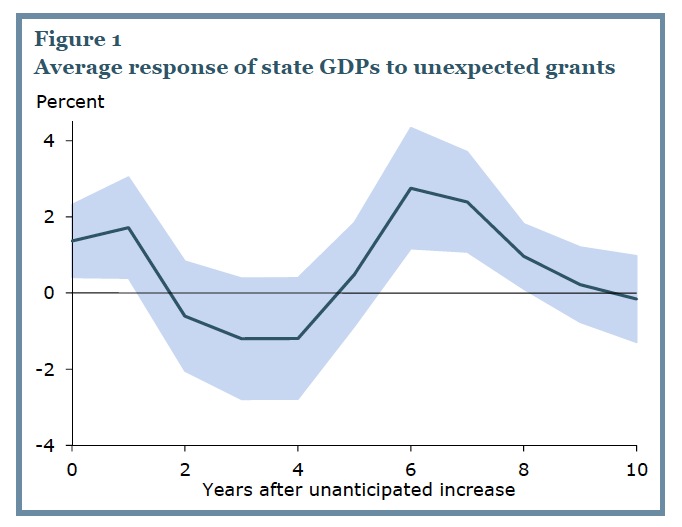

We find that unanticipated increases in highway spending have positive but temporary effects on GSP, both in the short and medium run. The short-run effect is consistent with a traditional Keynesian channel in which output increases because of a rise in aggregate demand, combined with slow-to-adjust prices. In contrast, the positive response of GSP over the medium run is in line with a supply-side effect due to an increase in the economy’s productive capacity.

We also assess how much bang each additional buck of highway spending creates by calculating the multiplier, that is, the magnitude of the effect of each dollar of infrastructure spending on economic activity. We find that the multiplier is at least two. In other words, for each dollar of federal highway grants received by a state, that state’s GSP rises by at least two dollars.

The Federal-Aid Highway Program

The federal government’s involvement in financing road construction goes back to the early part of the past century. Although initially small, this involvement became much more significant in 1956 with the enactment of the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which authorized almost $34 billion in 1956 dollars over 13 years for the construction of the Interstate Highway System. At the time, The New York Times noted that “the highway program will constitute a growing and ever-more-important share of the gross national product … (affecting) every phase of economic life in this country.”

The Interstate Highway System was completed in 1992. Since then, the federal government has continued to provide funding to states mostly through a series of grant programs collectively known as the Federal-Aid Highway Program (FAHP). The FAHP helps fund construction, maintenance, and other improvements on a wide range of public roads beyond the interstate highways. Local roads are often considered federal-aid highways and are eligible for federal funding, depending on how important the federal government judges them to be.

Because road projects typically take a long time to complete, advance knowledge of future funding sources can help smooth planning. Congress designs transportation legislation to minimize uncertainty. First, it enacts legislation that typically extends five to six years. Second, it apportions funds to states according to set formulas. Thus, a typical highway bill will specify an annual national amount for each highway program over the life of the legislation and spell out the formula by which that program’s national amount will be apportioned to states. Importantly, these formulas are based on road-related metrics measured several years earlier. That means that changes to current and future highway funding are not driven by current economic conditions.

Highway bills generally include information that helps states forecast relatively accurately the amount of grants they are likely to receive while the legislation is in effect. For the past two highway bills, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published forecasts of each state’s annual future grants under each program.

Download full report (PDF): Highway Grants: Roads to Prosperity?

About the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

www.frbsf.org

“The Federal Reserve System is the central banking system of the United States. It was created in 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act. Its duties today are to conduct the nation’s monetary policy, supervise and regulate banking institutions, maintain the stability of the financial system and provide financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions.”

Tags: CA, California, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Infrastructure Investment, San Francisco

RSS Feed

RSS Feed