NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL (NRDC)

Executive Summary

The funding gap for U.S. water infrastructure could exceed $1 trillion. Many decades-old drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems do not meet existing environmental and public health standards. Even more systems will need to be modernized to continue to meet these standards. Furthermore, our water infrastructure was never designed for the impacts of climate change, including the increasing frequency of droughts and sea level rise, so many existing systems will need to be redesigned or relocated.

The funding gap for U.S. water infrastructure could exceed $1 trillion. Many decades-old drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems do not meet existing environmental and public health standards. Even more systems will need to be modernized to continue to meet these standards. Furthermore, our water infrastructure was never designed for the impacts of climate change, including the increasing frequency of droughts and sea level rise, so many existing systems will need to be redesigned or relocated.

Congress established the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF) and Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) to provide states sustainable, long-term financial assistance to support communities’ water infrastructure needs. These funds have provided $151.2 billion in financial assistance since their inception, but their full potential remains untapped. This report describes actions that federal and state governments should take to more effectively leverage water infrastructure funding through State Revolving Funds (SRFs).

To help close the funding gap, there must be increased federal financial support for SRFs. Second, states need to make use of their ability to issue SRF-backed loan guarantees to communities. This would enable communities to more easily and cheaply raise funds from private financial markets. Third, states should leverage additional funding for their SRF programs through the issuance of bonds, which is a low-cost way to increase their SRFs’ financial capacity. Finally, Congress should grant states the flexibility to use newly generated funding for SRF grants or subsidized assistance.

These recommendations could help shrink the nation’s water infrastructure funding gap in a way that’s sustainable and equitable. It would also provide assistance for communities most in need, and help build the 21st century water infrastructure systems the entire nation needs.

America’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems are vital to communities’ well-being. But they are decades old and in need of a makeover in the next several decades. Legacy environmental and public health problems have been ignored for too long and many treatment plants need to be modernized or replaced. For example, in Flint, Michigan, in 2015, lead service lines contributed to a public health emergency. To simply meet and maintain existing health and environmental standards, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that the nation would need nearly $745 billion. That breaks out to $472.6 billion for drinking water and $271 billion for sewage systems and stormwater.

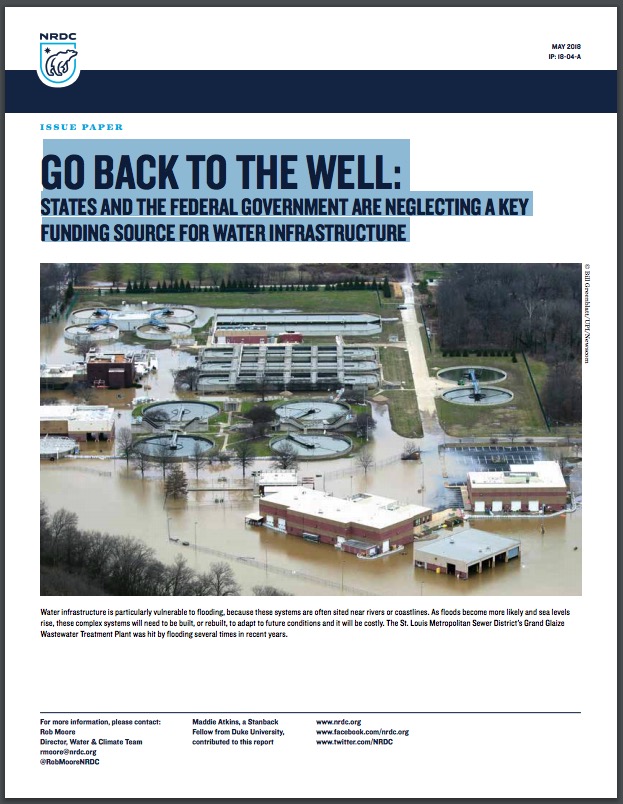

And that price tag doesn’t even include potential costs from the looming threat of climate change and the number of water systems that, as a result, will need to be re-engineered—and in some cases relocated—to cope with sea level rise, floods, and droughts. To adequately address the rising number of these incidents, the nation may need an additional $448 to $944 billion by 2050. Our water infrastructure is already suffering from these events. Between 1998 and 2014, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) spent $7.4 billion just to repair water and sewer infrastructure damaged by floods and coastal storms.

After Hurricane Ivan struck in 2004, Pensacola, Florida paid $300 million to move an aging sewage treatment plant to a new location that was better protected from flooding and less vulnerable to sea level rise. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy caused more than $5 billion in damage to wastewater infrastructure in New York and New Jersey and hundreds of millions more was spent to make these systems less vulnerable to similar events in the future. Communities across the country will face the same challenges in the future. A study by Argonne National Laboratory and the University of California-Berkeley found that 162 wastewater treatment plants serving 10.4 million Americans are at risk of flooding with three feet of sea level rise. With six feet of sea level rise, the numbers increase to 394 wastewater treatment plants serving 31.6 million Americans.

NRDC has identified four actions that federal and state governments can take to help close the funding gap:

- Congress should triple appropriations for the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds from the current level of approximately $2 billion to $6 billion annually.

- States should make loan guarantees available to more easily and cheaply finance drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater projects.

- States should leverage additional funding for their SRF programs through the issuance of bonds.

- Congress should allow states that increase the funding of their SRFs to provide additional subsidized assistance in order to meet the needs of low-income communities and catalyze investments in projects that are currently underrepresented in SRF portfolios.

The SRFs are an obvious and underused vehicle for these critical investments. The federal government should provide additional financial support and states should contribute much more.

State Revolving Funds for Water Infrastructure: an Overview

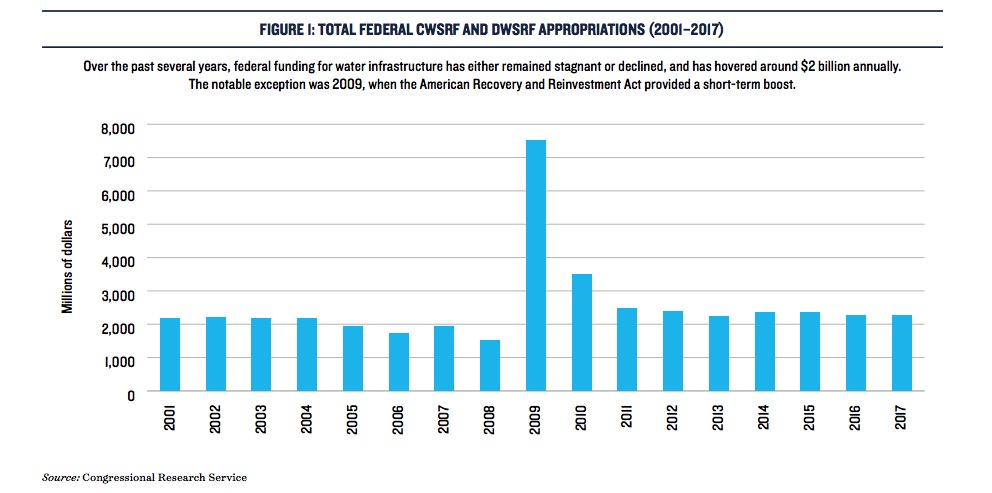

Congress established the CWSRF and DWSRF in hopes that they would provide states with a stable source of long-term funding to meet their communities’ water infrastructure needs. All 50 states administer a CWSRF and a DWSRF. Each year, Congress appropriates funding for the SRFs. Between 2013 and 2017, it appropriated an average of $1.41 billion for the CWSRFs and $852 million for the DWSRFs.A study by the RAND Corporation showed that the federal government provided just 4 percent of annual funding for the nation’s water utilities in 2014, based on data from various sources.

Even worse, most states do little to expand the financial capacity of their SRF programs. Instead, they settle for the incremental growth afforded by annual federal grants, their minimum state matches, and interest payments on outstanding loans.

The EPA allocates these funds to states through annual capitalization grants that are based on a needs assessment. In order to receive this federal funding, states must provide matches totaling 20 percent of their annual capitalization grant from the EPA. Collectively, these SRF grants are the largest source of federal water infrastructure funding.

States use the SRFs mostly to provide low-interest loans to communities. But the SRF programs were intended to be much more than a source of low-interest loans. That’s why Congress allowed states to issue bonds through their SRF programs, enabling them to further increase the SRFs’ financial capacity. Congress also allowed states to issue loan guarantees in order to provide credit assistance for water infrastructure projects, making it easier for communities to secure private financing.

Communities submit applications for financial assistance from the SRFs. States score each application based on factors like population served and anticipated environmental or public health benefits. Given the available funding, states determine which communities will get assistance, and how much assistance they will receive. The vast majority of SRF assistance is administered in the form of low-interest loans.

Over the past several years, federal funding for water infrastructure has either remained stagnant or declined, without adjusting for inflation (see Figure 1). That means funding provided by state SRF programs is falling further behind the curve of mounting water infrastructure needs.

Even worse, most states do little to expand the financial capacity of their SRF programs. Instead, they settle for the incremental growth afforded by annual federal grants, their minimum state matches, and interest payments on outstanding loans. The interest payments account for approximately 2 percent of the repayments. This approach does not keep apace with the nation’s water infrastructure needs (see Figure 2).

Still, the SRFs have provided $151.2 billion to local communities since their inception. While this is a substantial amount of money, much more is needed. Federal funding certainly needs to increase, but states should also more effectively leverage the federal SRF dollars they already receive. SRF programs can do so much more than what they are currently doing, including:

- Provide low-interest or no-interest loans;

- Forgive all or a portion of loans, also known as subsidized assistance or additional subsidization;

- Provide loan guarantees to establish local revolving funds that are used for the same purposes as a state’s CWSRF;

- Provide debt guarantees or municipal bond insurance to enable a community to get private financing at advantageous terms; and

- Issue state bonds that are deposited back into the SRF, thereby increasing the SRF’s long-term financial capacity.

Underinvestment at the federal level and underutilization at the state level have left much of the SRFs’ capacity untapped. As a result, states are failing to provide all the funding that’s possible to ensure safe, reliable, and resilient water infrastructure.

Download full version (PDF): Go Back to the Well

About the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)

www.nrdc.org

The Natural Resources Defense Council works to safeguard the earth – its people, its plants and animals, and the natural systems on which all life depends.

Tags: Natural Resources Defense Council, NRDC, SRF, State Revolving Fund

RSS Feed

RSS Feed