MUNICIPAL ART SOCIETY OF NEW YORK

Preface: The Rise of Midtown

The history of East Midtown is not only central to understanding its development, but must also inform the decisions now being made to shape its future. East Midtown’s rich history reflects a continuous cycle of investment, careful planning, and reinvestment that created the world’s most important central business district. The past matters; it is this legacy that must be renewed as we look forward.

The rise of East Midtown is largely based on the expansion of New York City’s railway infrastructure. This era began in the late 1800s with the consolidation of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s railroad holdings into the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Shortly thereafter, Vanderbilt commissioned architect John B. Snook to design the first iteration of grand stations. Located at 42nd Street and Fourth Avenue, Grand Central Depot opened in 1871 and was recognized as one of the great pieces of civic architecture in the United States.

In the years that followed railroad traffic grew rapidly, necessitating several phases of rail yard and depot expansion and improvement. Towards the end of the century, the number of trains operating to and from Grand Central had grown threefold and the old depot was struggling to meet demands. To manage the increased demand, in 1899 New York Central’s chief engineer William Wilgus proposed a plan involving the electric operation of trains, and the reconfiguration and construction of new tracks. The plan also introduced the idea of constructing a multi-level terminal to support the increased capacity. Although approved, the plan was set aside for several years until a tragic train accident in 1902 led to legislation outlawing steam engines south of the Harlem River. The railroad moved forward with Wilgus’ electrification plan, as well as with erecting a new depot to accommodate the growing train ridership. A design competition was held and won by architecture firm Reed & Stem, who with architects Warren & Wetmore designed the current Grand Central Terminal, completed in 1913.

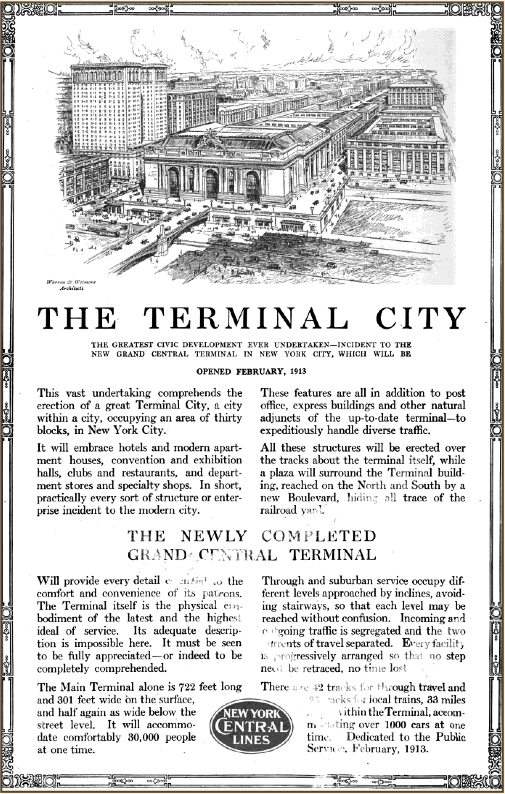

Wilgus devised a plan to fund the Terminal and take advantage of the newly electrified trains by cov- ering the tracks from 42nd to 50th streets between Madison and Lexington Avenues, and selling or leasing the development rights above them to accom- modate income-producing hotels, office buildings, apartments, clubs and retail stores. The “air rights” concept was born. A subsidiary company was formed by the railroad to run New York Central’s real estate business, and development began prior to the com- pletion of the Terminal. An advertisement ran in Harper’s Weekly on January 25, 1913 describing the project as a “great Terminal City, a city within a city.” The New York Central Railroad was responsible for transforming the area around Grand Central from a formerly sooty railway into a new business district (Middleton, 1977)

The master plan for Terminal City laid out a specific set of design guidelines for new buildings. The structures immediately surrounding Grand Central would be similar in height, construction materials and design, with prominent stone base, cornice and classical detailing. These new buildings were intended to complement and enhance Grand Central’s architectural significance in the neighborhood.

While the Terminal City design guidelines were developed by the team of architects responsible for Grand Central, a number of other architectural firms played a role in the actual design and subsequent development that lasted through the late 1920s. Architects James Gamble Rogers, Cross & Cross, George B. Post & Sons, and Sloan & Robertson designed some of their best work in Midtown Manhattan. When fully developed in the late 1920s, Terminal City had a post office; eight major luxury hotels (among them the Waldorf-Astoria, Roosevelt, and Barclay hotels); eleven office buildings (including the New York Central, Postum, and Graybar buildings); six luxury apartment buildings lining Park Avenue; an exhibition hall (Grand Central Palace, later demolished), and the Yale Club, conveniently located for a jaunt to New Haven. The area soon emerged as a premier business district as well as one of the most architecturally significant areas of New York City.

The covering of the railroad tracks and construction of Grand Central Terminal quickly transformed the neighborhood. Terminal City was an enlightened attempt at city planning in the Beaux-Arts tradition: on a very large scale and with an integrated frame- work: transportation, public space, and aspirational new design. It created a new fashionable district, and at its core the formerly derelict Fourth Avenue — reimagined as “Park Avenue” — became a tree-lined grand boulevard with a broad landscaped central median. Park Avenue became one of the most prestigious residential districts in the nation, further augmented to the north by the construction of luxury elevator apartment buildings. Lexington Avenue to the east became a respite for weary travelers, where several hotels were developed in the 1920s in close proximity to the city’s classically-designed convention center. On the nearby side street blocks, older row houses were purchased by wealthy owners, who hired architects to design new town houses or to alter existing buildings with new facades.

Read full report (PDF) here: East Midtown

About The Municipal Art Society of New York (MASNYC)

www.mas.org

“The Municipal Art Society is New York’s leading organization dedicated to creating a more livable city. For 120 years, MAS—a nonprofit membership organization—has been committed topromoting New York City’s economic vitality, cultural vibrancy, environmental sustainability and social diversity. Working to protect the best of New York’s existing landscape, from landmarks and historic districts to public open spaces, MAS encourages visionary design, planning and architecture that promote resilience and the livability of New York.”

Tags: East Midtown, MASNYC, Municipal Art Society of New York

RSS Feed

RSS Feed