POST CARBON INSTITUTE

Drill, Baby, Drill: Can Unconventional Fuels Usher in a New Era of Energy Abundance?

Executive Summary

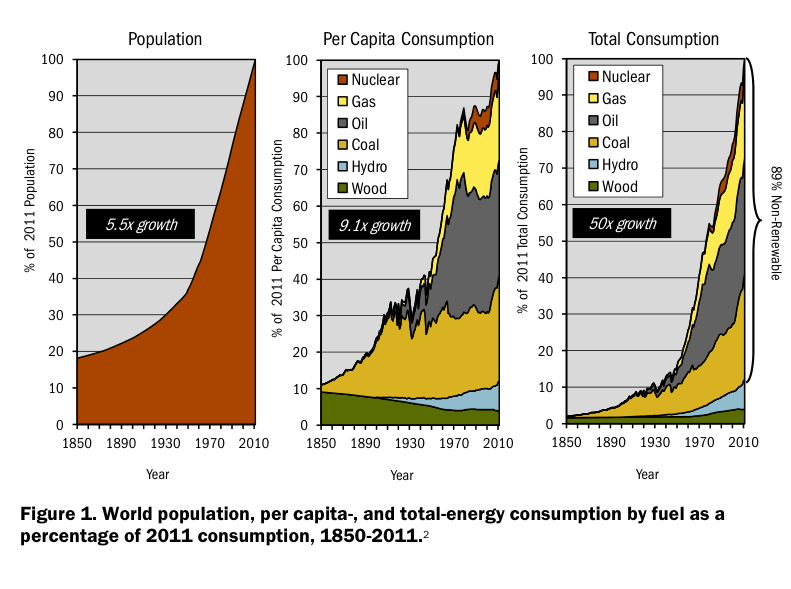

World energy consumption has more than doubled since the energy crises of the 1970s, and more than 80 percent of this is provided by fossil fuels. In the next 24 years world consumption is forecast to grow by a further 44 percent—and U.S. consumption a further seven percent—with fossil fuels continuing to provide around 80 percent of total demand.

Where will these fossil fuels come from? There has been great enthusiasm recently for a renaissance in the production of oil and natural gas, particularly for the United States. Starting with calls in the 2008 presidential election to “drill, baby, drill!,” politicians and industry leaders alike now hail “one hundred years of gas” and anticipate the U.S. regaining its crown as the world’s foremost oil producer. Much of this optimism is based on the application of technologies like hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and horizontal drilling to previously inaccessible shale reservoirs, and the development of unconventional sources such as tar sands and oil shale. Globally there is great hope for vast increases in oil production from underdeveloped regions such as Iraq.

However, the real challenges—and costs—of 21st century fossil fuel production suggest that such vastly increased supplies will not be easily achieved or even possible. The geological and environmental realities of trying to fulfill these exuberant proclamations deserve a closer look.

Context: History and Forecasts

Despite the rhetoric, the United States is highly unlikely to become energy independent unless rates of energy consumption are radically reduced. The much-heralded reduction of oil imports in the past few years has in fact been just as much a story of reduced consumption, primarily related to the Great Recession, as it has been a story of increased production. Crude oil production in the U.S. provides only 34 percent of current liquids supply, with imports providing 42 percent (the balance is provided by natural gas liquids, refinery gains, and biofuels). In fact, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) sees U.S. domestic crude oil production—even including tight oil (shale oil)—peaking at 7.5 million barrels per day (mbd) in 2019 (well below the all-time U.S. peak of 9.6 mbd in 1970), and by 2040 the share of domestically produced crude oil is projected to be lower than it is today, at 32 percent. And yet, the media onslaught of a forthcoming energy bonanza persists.

Metrics: Size, Rate of Supply, and Net Energy

The metric most commonly cited to suggest a new age of fossil fuels is the estimate of in situ unconventional resources and the purported fraction that can be recovered. These estimates are then divided by current consumption rates to produce many decades or centuries of future consumption. In fact, two other metrics are critically important in determining the viability of an energy resource:

- The rate of energy supply—that is, the rate at which the resource can be produced. A large in situ resource does society little good if it cannot be produced consistently and in large enough quantities—characteristics that are constrained by geological, geochemical, and geographical factors (and subsequently manifested in economic costs). For example, although resources such as oil shale, gas hydrates, and in situ coal gasification have a very large in situ potential, they have been produced at only miniscule rates, if at all, despite major expenditures over many years on pilot projects. Tar sands similarly have immense in situ resources, but more than four decades of very large capital inputs and collateral environmental impacts have yielded production of less than two percent of world oil requirements.

- The net energy yield of the resource, which is the difference between the energy input required to produce the resource and the energy contained in the final product. The net energy, or “energy returned on energy invested” (EROEI), of unconventional resources is generally much lower than for conventional resources. Lower EROEI translates to higher production costs, lower production rates, and usually more collateral environmental damage in extraction.

Thus the world faces not so much a resource problem as a rate of supply problem, along with the problem of the collateral environmental impacts of maintaining sufficient rates of supply.

Read full report (PDF) here: Drill, Baby, Drill

About the Post Carbon Institute

www.postcarbon.org

“Post Carbon Institute provides individuals, communities, businesses, and governments with the resources needed to understand and respond to the interrelated economic, energy, environmental, and equity crises that define the 21st century. We envision a world of resilient communities and re-localized economies that thrive within ecological bounds.”

Tags: Alternative Fuel, Baby, Drill, Drill: Can Unconventional Fuels Usher in a New Era of Energy Abundance?, Fracking, Post Carbon Institute

RSS Feed

RSS Feed