MOUNTAIN PLAINS CONSORTIUM

ABSTRACT

Shortly after the advent of cars, a conflict arose between moving traffic and residential livability. The typical response was to push traffic off residential streets and onto nearby major roads. This line of thinking evolved into a more hierarchical approach to street network design and what are known as arterial roads designed to carry the vast majority of vehicle traffic. With many researchers – notably Donald Appleyard with his influential Livable Streets research strand – identifying traffic on residential streets as an underlying issue behind poor livability, this solution makes perfect sense. However, is the relationship between residential livability and traffic moderated by the character of the nearby arterial road? In other words, would living near a big, bad arterial road offset the livability benefits of living on a light traffic street? Alternatively, would residing near a more “livable” arterial neutralize some of the problems associated with living on a heavy traffic street?

Shortly after the advent of cars, a conflict arose between moving traffic and residential livability. The typical response was to push traffic off residential streets and onto nearby major roads. This line of thinking evolved into a more hierarchical approach to street network design and what are known as arterial roads designed to carry the vast majority of vehicle traffic. With many researchers – notably Donald Appleyard with his influential Livable Streets research strand – identifying traffic on residential streets as an underlying issue behind poor livability, this solution makes perfect sense. However, is the relationship between residential livability and traffic moderated by the character of the nearby arterial road? In other words, would living near a big, bad arterial road offset the livability benefits of living on a light traffic street? Alternatively, would residing near a more “livable” arterial neutralize some of the problems associated with living on a heavy traffic street?

This first part of this project sought to answer these research questions via a residential study of 10 Denver, CO, neighborhoods where we first selected 10 urban arterials that could be partitioned along two dimensions: high/low traffic and high/low design quality. Within each of the 10 surrounding neighborhoods, we selected comparable residential roads to fit Appleyard’s heavy, moderate, and light traffic descriptions where we then surveyed 721 respondents living along these 30 residential streets. Our results suggest that the surrounding street network – and in particular the character of the nearby arterial road – influences residential livability across a number of livability measures. When controlling for income, high levels of traffic as well as low levels of urban design on the arterial both detract from the livability of those living in the surrounding neighborhoods. Some results even suggest that residential streets with heavy traffic near a low traffic/high design arterial are just as livable, if not more so, than residential streets with light traffic near a high traffic/low design arterial. By no means should this be taken as a call to increase traffic on residential streets; rather, planners and engineers looking to promote residential livability need to begin taking a broader, network perspective to understanding livability. Livable residential streets can only be part of the solution; we also need more livable arterial roads.

The second part of the project examined: i) how residents perceive and use arterial roads, and ii) what specific characteristics of arterial roads associate with residential satisfaction. Using factor analysis and ordinal logistic regression, the results suggest that arterials perceived as being vibrant are associated with increased residential satisfaction – above and beyond other features of the residential environment – whereas arterials with perceived illicit activity and trash are associated with lower residential satisfaction. Our study includes three different measures of residential satisfaction, and the specific influence of the arterial road depends on whether one focuses more narrowly on satisfaction with the neighborhood street, satisfaction with the neighborhood, or overall sense of happiness living there. The results of this study point to land use policies, enforcement of social norms, and the design of pedestrian and transit environments as measures to maximize the contributions of commercial arterials to neighborhood livability.

The appendices include additional details on the survey and survey methodology as well as examples of how these issues were integrated into assignments for graduate level civil engineering and urban planning classes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Can traffic and livability coexist on residential streets? This issue became a concern of the Garden City movement in the early 1900s, was written about by Buchanan and his seminal work Traffic in Towns in the early 1960s, and was later documented by Donald Appleyard’s Livable Streets series of works starting in the late 1960s up through the early 1980s (Appleyard, 1978; Appleyard, Gerson, & Lintell, 1981; Appleyard & Lintell, 1972; Appleyard & Lintell, 1975). Elegant in its simplicity, Appleyard’s research found those living on high traffic streets tend to have lower perceived livability (in terms of issues such as traffic hazards, noise, pollution, social interactions, and territorial extent) (Appleyard & Lintell, 1972). Trying to preserve such residential livability in the face of increasing motorization and traffic was one of the many challenges that city planners continue to face. The typical response is to push traffic off residential streets and onto nearby major roads (i.e., arterials). As a result, most residential neighborhoods in the U.S. depend heavily on arterials for everyday travel and access to public transit, shopping, and other activities. It is also not uncommon for these arterial roads to carry tens of thousands of cars every day. While not necessarily ideal, the approach is logical and seemingly better than trying to accommodate significant traffic on nearby residential streets. Yet, concentrating heavy traffic onto a small fraction of the overall street network can burden adjacent neighborhoods and create barriers for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit riders. When traffic congestion becomes a problem on arterials, drivers may choose to cut through residential neighborhoods. With this project, we revisit the livable streets research strand from a broader network perspective. For example, does living near a big, bad arterial road offset the livability benefits of living on a light traffic street? Conversely, would living near a more “livable” arterial neutralize some of the problems associated with living on a heavy traffic street?

Numerous researchers from around the world have attempted to recreate and build off Appleyard’s influential study. Some of the more noteworthy papers – such as the 1999 paper “Livable Streets Revisited” by Bosselmann et al. – took into account new factors such as the design elements of multiway boulevards, finding that the effects of traffic can be alleviated with good street design (Bosselmann, Macdonald, & Kronemeyer, 1999). Our work represents a novel take on the livable streets question. The intent of this research is to shed light on the issue of residential livability and vehicle traffic with respect to how this relationship might be moderated by a nearby arterial road. To shed light on these questions, we selected 10 urban arterials in Denver, CO, partitioned along two dimensions: high/low traffic and high/low design quality. Within each of the surrounding neighborhoods, we selected comparable residential roads to fit Appleyard’s heavy, moderate, and light traffic descriptions. Via a residential survey, our research team gathered data from 721 respondents living along these 30 residential streets and collected built environment data for these streets as well as the corresponding arterials. The next section presents additional background and literature review, which is followed by a more detailed description of the survey, our methods, and the data collected. We then present our results with an eye toward the implications of this work for planners, engineers, and city dwellers.

2. BACKGROUND & LITERATURE REVIEW

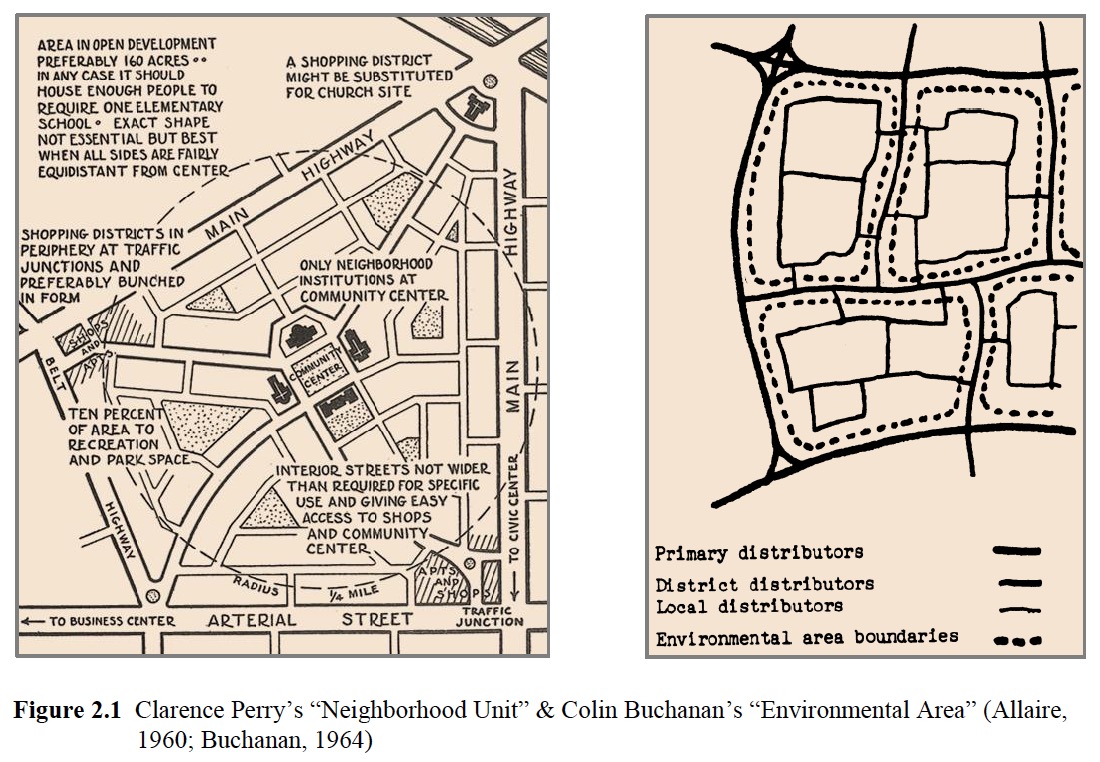

Most streets tend to have moving vehicle traffic, and most people tend to live on such streets. The inevitability of the resulting conflict became a cause for concern as early as 1898 with Sir Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City in the United Kingdom. (Meacham, 1999). Eventually, the Garden City movement made its way to the U.S. in Radburn, NJ, in 1929. Designed by Charles Stein and Henry Wright, Radburn was one of the first U.S. developments to explicitly limit the through movement of traffic on residential streets. Stein labeled cars a “menace to city life” and called the traditional approach to street network design “as obsolete as a fortified town wall” (Southworth & Ben-Joseph, 2003). Radburn not only kicked off an overhaul in U.S. street network design, but it also initiated a hierarchical approach to road typology. This principle was evident in Radburn and the “neighborhood units” of Clarence Perry in 1929 as well as with the “environmental areas” advocated by Colin Buchanan in Traffic in Towns in 1963 (Allaire, 1960; Buchanan, 1964). In both cases, shown in Figure 2.1, the design intentionally limits traffic on residential streets and displaces that traffic to the arterial streets and highways that envelop the residential neighborhoods. The underlying thinking of these planners is clear: living on a street with low levels of traffic has livability benefits.

About the Mountain Plains Consortium

http://www.mountain-plains.org/

The Mountain-Plains Consortium (MPC) theme is “Transportation Infrastructure and Operations to Support Sustainable Energy Development and the Safe Movement of People and Goods”. MPC is a competitively selected university program sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation through its Research and Innovative Technology Administration.

Tags: Carolyn A. McAndrews, CO, colorado, Complete Streets, Denver, Livability, Liveability, Mountain-Plains Consortium, MPC, UGPTI, Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute, Wesley E. Marshall

RSS Feed

RSS Feed