URBAN GREEN COUNCIL

Executive Summary

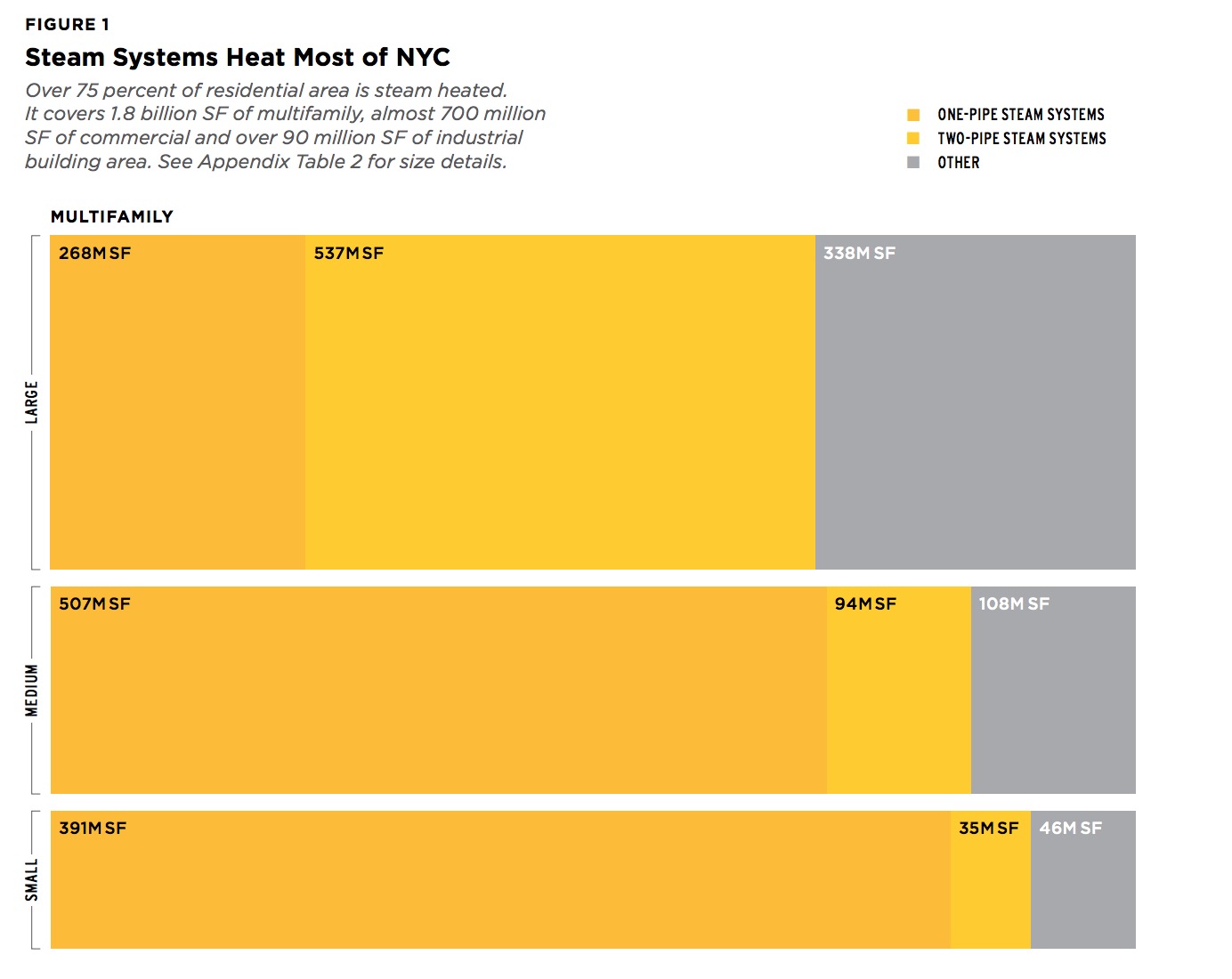

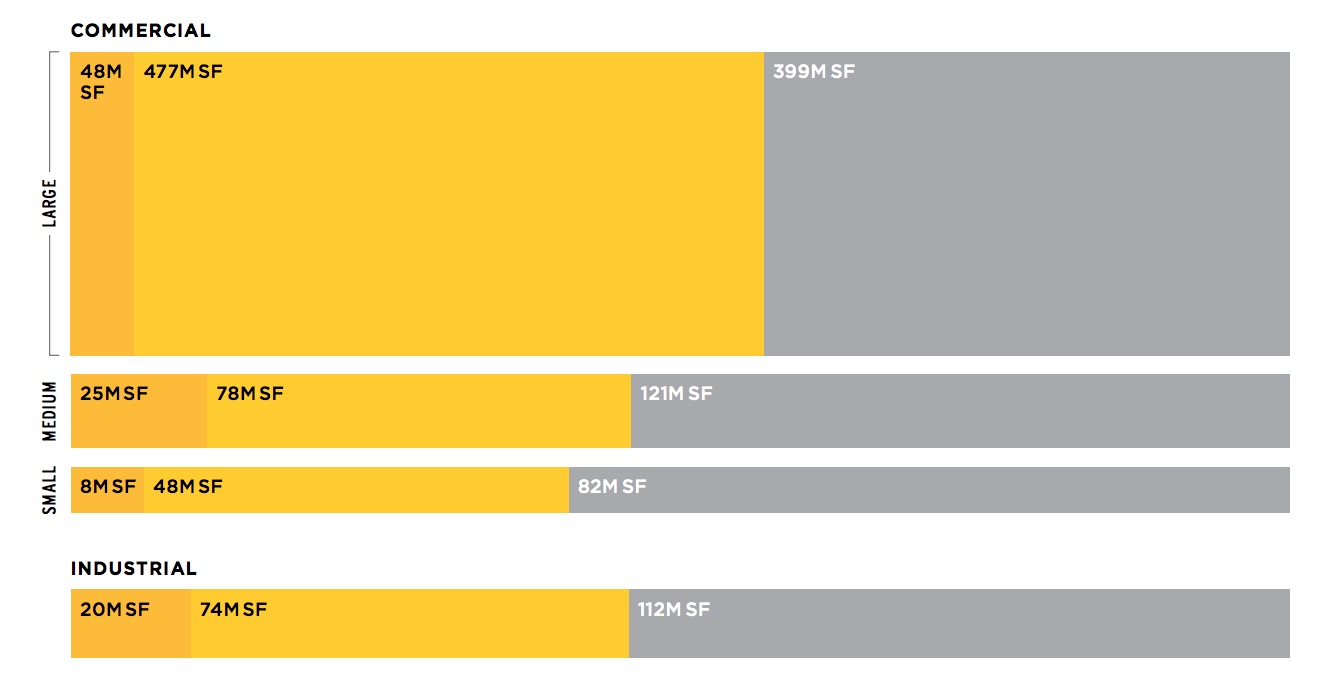

In New York City, roughly 80 percent of residential buildings are heated by steam. There’s a good chance you live in one and, if so, you’ve become accustomed to uneven heating, open windows in the dead of winter, and high heating bills. Indeed, heating is the biggest utility expense for most residential buildings in New York State. But there’s good news: Heating also offers the biggest opportunities for savings.

In New York City, roughly 80 percent of residential buildings are heated by steam. There’s a good chance you live in one and, if so, you’ve become accustomed to uneven heating, open windows in the dead of winter, and high heating bills. Indeed, heating is the biggest utility expense for most residential buildings in New York State. But there’s good news: Heating also offers the biggest opportunities for savings.

New Yorkers can save significant energy and money by updating steam systems. Heating is the largest source of energy consumption in residences across the United States, and if New York can marshal widespread steam heat improvements, then other major U.S. cities in cold-weather regions, like Boston and Chicago, might follow suit.

Demystifying Steam describes steam heat and how it can be improved to save money and energy. It also explores the future role of steam in NYC buildings.

In particular, the Demystifying Steam report:

- Identifies steam system problems affecting building owners, managers and occupants;

- Details the prevalence of steam systems in New York City and discusses how experts improve common steam systems;

- Suggests best practices and policies the city and/or state could pursue to capture most or all of the savings from improving steam heat;

- Analyzes the costs, as well as the potential carbon and fuel savings of improving steam heat in New York City and across the state;

Steam heat revolutionized heating technology. It replaced fireplaces and stoves, offering better indoor air quality, comfort and efficiency. Today, over 100 years later, the steam systems that heat our homes haven’t changed much. But what passed for efficiency and comfort in the 20th century is no longer acceptable. Our survey of New York City tenants with steam heat found that nearly 70 percent are chronically overheated in winter. Many tenants open windows for relief, even on the coldest days. But steam systems are so unbalanced that other residents in these same buildings don’t receive enough heat.

In other words, we’re burning through significant amounts of gas and oil to keep New Yorkers uncomfortable. A 2016 performance analysis showed that fuel consumption in steam heating systems varies widely.1 Neglect has led to overheating and undiscovered boiler-killing leaks. These systems could be retrofitted to use less fuel. Additionally, converting steam to hydronic heating has yielded as much as 50 percent fuel savings in buildings throughout New York.

With upgrades and more consistent maintenance, it’s possible to improve efficiency and comfort. Adding sufficient venting and simple valves can improve distribution and give residents better control over temperature. Controls can also be installed that respond to indoor rather than outdoor temperature.

Oversized boilers are another problem. Without a properly sized boiler—one that provides heat where it needs to and without excess—even a well-maintained system will be inefficient. Boilers can last for more than 30 years, so timely boiler replacement with proper planning is critical. When the boiler is ready to be replaced, properly installing a right-sized boiler can increase system efficiency and reduce fuel costs by 5 percent or more.

For New York City to continue to reduce building emissions, improvements to steam heat must be implemented now. Our research found that retrofitting steam systems in New York City buildings larger than 5,000 square feet would cut that sector’s fuel consumption by 19 percent.

The improvements recommended in this report can be made by investing less than a dollar per square foot. If improvements are made at the time of a planned boiler replacement, the reduced cost of a smaller boiler will help offset the cost of distribution upgrades. Afterward, heating and hot water expenses would drop by roughly 20 percent—with distribution improvements typically responsible for two-thirds of these savings.

Making steam as efficient as possible over the next 10 years will save building owners and tenants money, avoid cumulative emissions, and improve resident comfort. In the long run, however, more will be needed to meet New York City’s 80×50 carbon reduction goals. To achieve 80×50, we must cut 80 percent of 2005 emissions—over 33 million metric tons of carbon in buildings alone—by 2050 (80×50). That’s a herculean task that would have the same climate benefits as closing eight coal-fired power plants.

Even if every residential steam system was retrofitted for maximum efficiency, residential steam heat would consume the citywide carbon budget for buildings in 2050, before electricity use or non-residential buildings are considered.5 The state’s greenhouse gas reduction goals of 40 and 80 percent by 2030 and 2050 respectively will require building owners to pursue non-fossil fuel heating technology.

In the long term, to increase tenant comfort and radically reduce New York City’s emissions, we need to convert or replace our outdated steam heat systems with modern heating alternatives. In the medium-term, however, fixing steam is a highly cost-effective measure that will buy us time to move away from fossil fuels altogether. But we must act immediately if we wish to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change.

Background

The advent of steam heat revolutionized building comfort and safety. Yet as buildings have advanced over the last hundred years, steam systems have changed far less.

The ability to harness heat is central to the success of human civilization. Throughout history, people gathered around fires to cook food, ward off predators, and of course, to keep warm. As human life moved indoors, we designed fireplaces and stoves to capture heat and contain it within the built environment. These early space heating systems were inefficient, and the development of steam heat made comfort more consistent throughout the building while improving safety by isolating fuel burning to the basement.

One of the earliest uses of steam heat was in the 17th century, when it was piped into greenhouses to keep plants warm. That nascent idea was iterated on many times until James Watt, celebrated for his steam engine, used it to heat his study in the winter of 1784-85. He founded his system on a simple thermal cycle: Fire heats water until it boils and becomes steam. The steam travels through distribution pipes, releases heat, and then conveniently condenses back into water. Gravity brings that water back to the boiler and the process repeats. This system spread and developed rapidly; it reached American homes by 1855, when steam heat was installed in President Pierce’s White House.

The history of steam heat offers clues as to how we can improve these systems today. In the early days of the 20th century, there was a widely-held fear of stagnant air, so people kept their windows open throughout the year. To avoid complaints, builders recommended boilers and radiators that were large enough to heat buildings on the coldest days of the year, with the windows open.

After World War I, the dominant fuel source for central heating changed several times, from coal to oil to natural gas, which now fuels 64 percent of NYC steam systems. Replacement equipment was sized unsystematically and included a generous safety factor to ensure replacement boilers were not too small to heat the necessary space.

Over the years, buildings were retrofitted with double-pane windows that retain heat more effectively than older single-pane models. Insulation and air sealing are now a part of the building energy code and included in some retrofits. But most steam systems in New York City were not modified to account for these changes. People still open their windows in the winter, not out of fear of stagnant air, but because their apartments are overheated by oversized steam systems.

Not surprisingly, steam heat is no longer viewed as the optimal solution. It’s uncommon in new construction, however, the technology persists in existing buildings. The result is poorly maintained and inappropriately sized systems that waste energy, release excess greenhouse gas emissions and overheat some rooms while leaving others cold.

Download full version (PDF): Demystifying Steam

About the Urban Green Council

https://www.urbangreencouncil.org

Urban Green Council is the New York affiliate of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). Our mission is to transform NYC buildings for a sustainable future. We believe the critical issue facing the world today is climate change. Our focus on climate change requires us to target energy and other resource management. As we improve energy and other resource management, we can deliver a more resilient, efficient, healthy and affordable city.

Tags: New York, New York City, NY, NYC, Steam, Steam Heat, Urban Green Council

RSS Feed

RSS Feed