SMART GROWTH AMERICA

Executive Summary

More than 1,200 Complete Streets policies are now in place at the state, regional, and local levels. And over the last year, federal agencies have followed suit with new changes in national policy intended to make streets safer for everyone.

These policies are a good starting point, but alone are not enough to keep people safe while walking on America’s streets. Between 2005 and 2014, a total of 46,149 people were struck and killed by cars while walking. In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, 4,884 people were killed by a car while walking—105 people more than in 2013. On average, 13 people were struck and killed by a car while walking every day in 2014. And between 2005 and 2014, Americans were 7.2 times more likely to die as a pedestrian than from a natural disaster. Each one of those people was a child, parent, friend, classmate, or neighbor. And these tragedies are occurring across the country—in small towns and big cities, in communities on the coast and in the heartland.

Dangerous by Design 2016 takes a closer look at this alarming epidemic. The fourth edition of this report once again examines the metro areas that are the most dangerous for people walking. It also includes a racial and income-based examination of the people who are most at risk, and for the first time also ranks states by their danger to pedestrians.

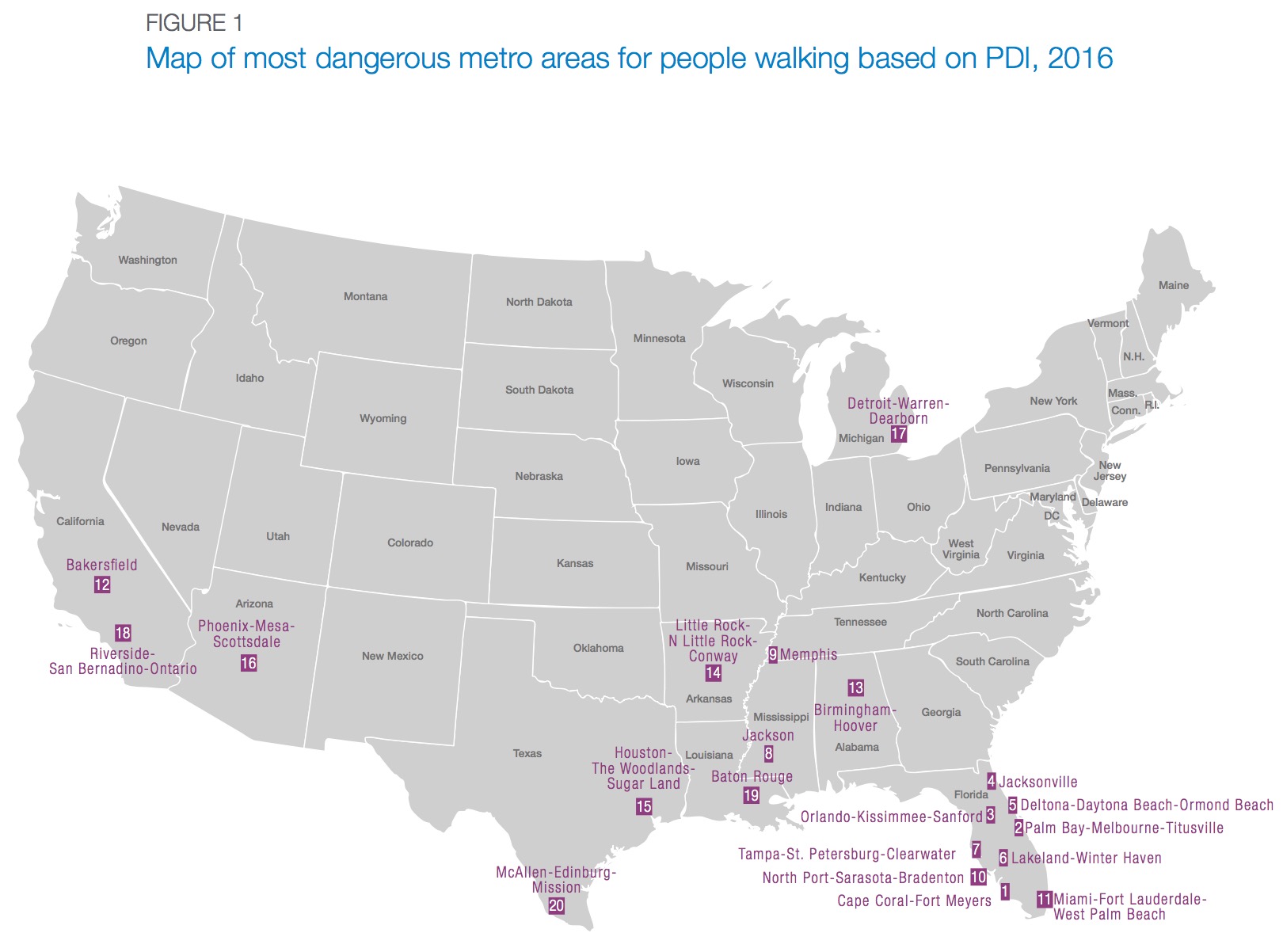

Dangerous by Design ranks the 104 largest metro areas in the country, as well as every state, by a “Pedestrian Danger Index,” or PDI. PDI is a calculation of the share of local commuters who walk to work and the most recent data on pedestrian deaths.

Based on PDI, the 20 most dangerous metro areas for walking in the United States are shown in Figure 1, on page iii.

Who are the victims of these collisions? People of color and older adults are overrepresented among pedestrian deaths. Non-white individuals account for 34.9 percent of the national population but make up 46.1 percent of pedestrian deaths. In some states, this disparity is even starker. In North Dakota, for example, Native Americans make up just five percent of the population but account for almost 38 percent of pedestrian deaths. Older adults are similarly at higher risk: individuals 65 years or older are 50 percent more likely than younger individuals to be struck and killed by a car while walking.

Even after controlling for the relative amounts of walking among these populations, risks continue to be higher for some people of color and older adults—indicating that these people most likely face disproportionately unsafe conditions for walking. In 2014, an average of four people of color were struck and killed while walking every day—and these numbers are likely low, due to lack of adequate data. In 2014, an average of 13 people were struck and killed every day. Of those, four were people of color and two were over 65.

In addition, PDI is strongly correlated with median household income and rates of uninsured individuals. Low-income metro areas are predictably more dangerous than higher-income ones: as median household incomes drop, PDI rises. Similar trends bear out with rates of uninsured individuals: as rates of uninsured individuals rise, so do PDIs, meaning that the people who can least afford to be injured often live in the most dangerous places. The temptation is to think this may be due to lower income people walking more but this study seeks to control for that.

The way we design streets is a factor in these fatal collisions. Many of these deaths occur on streets with fast-moving cars and poor pedestrian infrastructure. People walk along these roads despite the clear safety risks—a sign that streets are not adequately serving everyone in the community.

Everyone involved in the street design process—from federal policymakers to local elected leaders to transportation engineers— must take action to end pedestrian deaths and make roads safer for everyone. So long as streets are built to prioritize high speeds at the cost of pedestrian safety, this will remain a problem. And as the nation’s population grows older on the whole, and as we become more diverse both racially and economically, the need for these safety improvements will only become more dire in years to come.

Dangerous by Design 2016 outlines where to focus these actions and the first steps to making it happen.

Introduction

One Friday night in August 2014, Thomas DeSoto decided to go out for a sandwich. Thomas, then 68, lived in Cape Coral, FL, and for years he had worked in patient care at hospitals in the area before retiring.

Thomas left his home and walked out to Fowler Street. As he was crossing the five-lane arterial, a driver struck him and quickly fled, later being arrested and charged with a hit-and-run and tampering with evidence. Thomas died of his injuries at the scene.

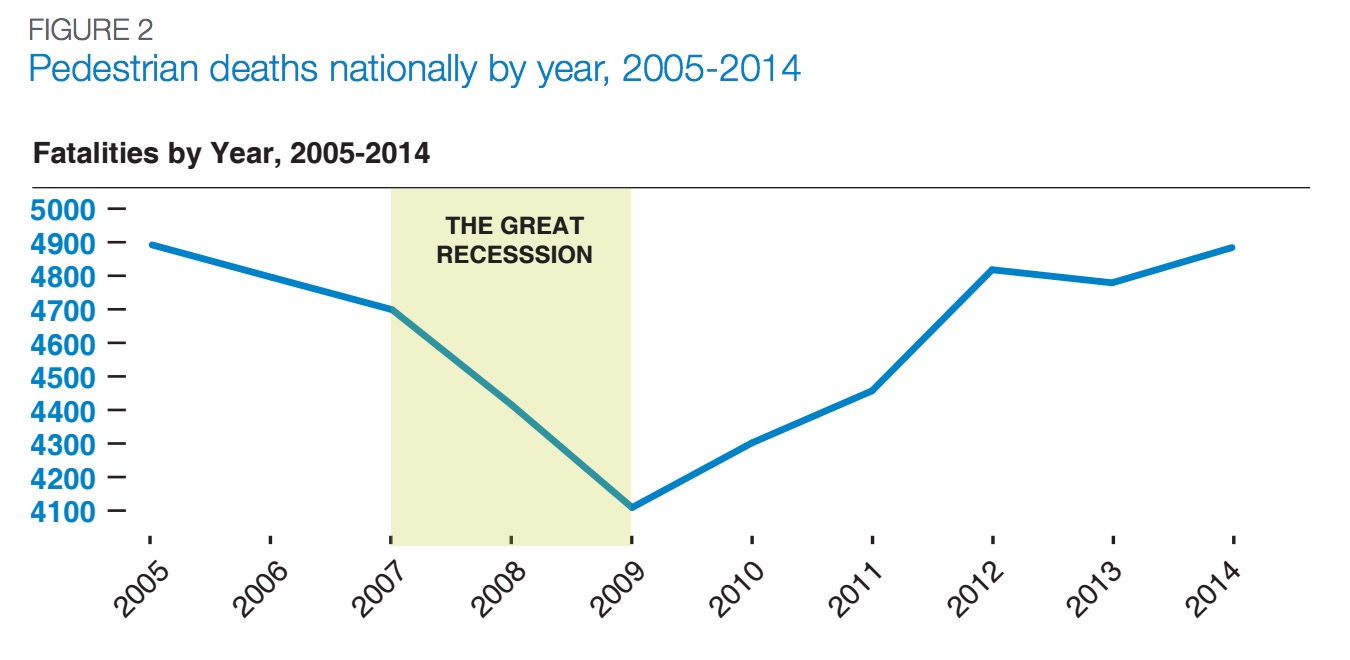

This story is as tragic as it is common. Each year in the United States, thousands of people are struck and killed by cars while walking. Between 2005 and 2014, a total of 46,149 people were killed by cars while walking. In 2014, the most recent year for which data are available, 4,884 people were killed by cars while walking, continuing the upward trend that has persisted since 2009 (see Figure 2, below).

Traffic crashes were the second-leading cause of unintentional injury death in the United States between 2011 and 2014.2 On average, 13 people were struck and killed by cars while walking every day in 2014. And between 2005 and 2014, Americans were 7.2 times more likely to die as a pedestrian than from a natural disaster.

And while cars have become increasingly safe for the people inside, we have failed to make similar strides to protect people who are walking. Pedestrians now comprise a larger share of traffic deaths than before: between 2003 and 2012, 12.3 percent of the people killed in car crashes were pedestrians. Between 2005 and 2014, that number rose to 12.7 percent.

Disturbingly, this is happening at a time when the country’s top health experts are encouraging Americans to walk more. The nation faces well-known problems related to lack of physical activity: one out of every two U.S. adults is living with a chronic disease like heart disease, cancer, or diabetes, and these diseases contribute to disability, premature death, and rising health care costs. To reverse these trends the U.S. Surgeon General has urged Americans to get more physical activity, and specifically encouraged people to walk to school, work, or around their neighborhood. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends Complete Streets as one strategy for promoting health. Yet too often that is a dangerous or potentially deadly prescription.

Nowhere is this more true than in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. These communities already face higher rates of obesity-related diseases.8 As this report shows, people in these communities are also at higher risk of being struck and killed while walking.

We must use every tool available to improve safety for pedestrians. Ending drunk or distracted driving, enforcing speed limits, and reminding pedestrians to cross streets safely are all important parts of this effort. So too is better, safer street design.

The way we design, plan for, and build streets is an enormous part of both this problem and its solution. Streets without sidewalks or pedestrian crossings, with wide lanes that encourage people to drive fast are simply designed to be dangerous for people walking. People walk along these roads despite the clear safety risk. This is not user error. Rather, it is a sign that these streets are failing to adequately meet the needs of everyone in a community.

Policymakers across governments can do more to make sure streets are routinely designed and operated to enable safe access for all users, regardless of age, ability, income, race, ethnicity, or mode of transportation—and in many places, they have. Over the last 10 years, more than 1,200 communities nationwide have passed local Complete Streets policies, and for the first time in history, Complete Streets provisions were included in Congress’s 2015 federal transportation bill.

We must now turn those ideas into practice and implement Complete Streets policies. It will take all of us working together to make streets across the country less dangerous by design.

Between 2005 and 2014, a total of 46,149 people were killed by cars while walking. The majority of these fatalities occurred in densely populated cities like San Francisco and New York. Taken at face value, these numbers might make these places seem extremely dangerous to walk. But with much larger populations and much higher rates of walking than other places in the country, measuring deaths in these places without context is misleading.

Download full version (registration required): Dangerous by Design 2016

About Smart Growth America

smartgrowthamerica.org

Smart Growth America advocates for people who want to live and work in great neighborhoods. We believe smart growth solutions support thriving businesses and jobs, provide more options for how people get around and make it more affordable to live near work and the grocery store. Our coalition works with communities to fight sprawl and save money. We are making America’s neighborhoods great together.

Tags: Complete Streets, Dangerous By Design, Pedestrian, safety, SGA, Smart Growth, Smart Growth America, Walking

RSS Feed

RSS Feed