THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

Introduction

The 2016 election revealed a dramatic gap between two Americas—one based in large, diverse, thriving metropolitan regions; the other found in more homogeneous small towns and rural areas struggling under the weight of economic stagnation and social decline.

The 2016 election revealed a dramatic gap between two Americas—one based in large, diverse, thriving metropolitan regions; the other found in more homogeneous small towns and rural areas struggling under the weight of economic stagnation and social decline.

This gap between two American geographies came as a shock to many observers.

While it is true that some members of the media and policy analysts had grown disconnected from a significant portion of the country, something else had happened, too: the nation’s economic trends had changed. For much of the 20th century, reality conformed to economists’ predictions that market forces would gradually diminish job, wage, investment, and business formation disparities between more and less developed regions.

As recently as 1980, the wage gap between regions was shrinking while growth in rural areas and small towns led the country from recession to recovery in the 1990s.

Recent decades, however, have witnessed a massive shift in the relationship between the nation’s biggest, most prosperous metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. Globalization has weakened the supply chains that once connected these regions. The rise of the information economy has boosted the returns to urban skills and diminished the importance of the resources and manual labor that non-metropolitan areas provided during the heyday of the manufacturing economy. And for that matter, high-tech manufacturers that still depend on supply chains to produce physical goods—and might once have sourced from the American “heartland”—have instead moved production and assembly functions overseas.

As a result, the lion’s share of growth in the last decade has been concentrated—with relatively few exceptions—in a small cohort of urban hubs while the rest of the country has drifted or lost ground. Nearly a decade after the end of the recession, many small towns and rural areas have yet to return to their 2008 employment levels. If the half century after the New Deal was one of regional convergence, future historians may well regard the current era as a time of divergence.

Public policy has done little to halt or even mitigate this trend. Indeed, taken as a whole, the policies of recent decades have almost certainly exacerbated it. The deregulation of transportation and finance along with the failure to update and enforce antitrust policies worked against less densely populated areas. Ill-conceived regulations in large cities have driven up housing costs, discouraging the movement of lower-skilled workers to rapidly growing areas. At the same time, no urgent digital skills or serious technology-oriented regional growth strategy has sought to promote what the investor Steve Case calls the “rise of the rest.” Perhaps most importantly, our failure to craft effective, place-sensitive policies has allowed growth and opportunity to concentrate in fewer and fewer places while leaving others behind.

Now, the political impacts of these sins of omission and commission are clear. As the country has pulled apart economically, it is also pulling apart politically. Political parties that once brought voters together across regional lines now focus their appeal on the particular interests and outlook of a single kind of region. In the United States and throughout the West, parties with their principal support in metropolitan areas do battle with parties based in less densely populated areas. And while compelling research has underlined the strong role of racial and xenophobic cultural factors in explaining backlash politics, it has become clear that the backlash also has geographic and economic dimensions. One economic order, and set of places, wars with another one. Making matters even worse, these political divisions mirror widening differences between diverse, liberal, internationally minded cities and more homogenous, conservative, and locally focused small towns and rural areas, spawning a new culture war.

The crystallization of these dueling political identities has shaken the liberal democratic order in the United States and beyond. Throughout the West, parties representing those who feel that they have lost out stand opposed to parties representing those who have benefitted from the economic and cultural changes of recent decades. Not surprisingly, the “losers” have seen the ballot box as their last chance to reverse their declining fortunes. In the United States, their political voices are amplified by systems of representation that favor rural residents, triggering political resentment among urbanites that mirrors economic and cultural resentment in the countryside. In this way, the populist politics produced by economic change, and the polarization that results, constitute an externality few economists anticipated but can no longer afford to ignore.

To expand opportunity and reduce political polarization, we need new understandings and new policies unshackled from past assumptions. In the realm of understanding, greater recognition of the trends underway and their sources and drivers is imperative. Greater attention to the power and consequences of spatial dynamics is critical. In addition, three intellectual shifts are key.

First, we must reject the false choice between policies that target people and those that target places. We can do both, and both are needed. There is no contradiction between moving people to opportunity and bringing opportunity to people where they are. Each approach is valid for certain populations in particular places at particular times.

Second, we must reject the false assumption that adopting place-sensitive policies will necessarily come at the expense of economic efficiency. Indeed, there is evidence that our failure to think spatially has actually diminished aggregate economic output.

And third, we must discard economic myopia in favor of a broader view of costs and benefits. Leaving struggling places to fend for themselves may reduce public outlays today, only to increase them tomorrow as the consequences of neglect manifest themselves in increased costs for health care, disability, and substance abuse programs. Lower labor force participation, moreover, will restrict prospects for economic growth, a trend that will prove increasingly damaging as our population ages.

In keeping with these priorities, the discussion that follows describes the changing geography of prosperity and its drift toward regional divergence. We identify some of its sources and explore how the economics of divergence have helped produced a politics of divergence.

We then argue that inaction is no longer an option, note some of what won’t work in mitigating the worst geographic divisions, and advance five strategies for responding to the current dynamics.

The nation is only in the earliest stages of developing the place-sensitive strategy our time requires. The recommendations we offer in this paper represent early sketches, designed to provoke additional creative thinking.

But if we do not yet know what will succeed, we already know what will fail. Neither nostalgia nor neglect offers hope for a better future.

Whatever we do, traditional mining and manufacturing will never again provide a future of opportunity for the majority of our population, certainly not in less-populated areas. We cannot turn the clock back, and the effort to do so will leave its intended beneficiaries no better off than they are today—only more frustrated.

We have tested the alternative to nostalgia— namely, neglect based on the assumption that the market would suffice to spread opportunity across the country. It has not and cannot do so. While our place-sensitive policies must build on the economy of the present and future, not the past, they must also push against the forces that have produced—and, if left unchecked, will sustain—the Great Divergence that has polarized our politics and constrained life-chances for millions of Americans.

From Convergence to Divergence

For much of the 20th century, economists projected that the disparities between regions— including differences in wages, unemployment, and business formation patterns—would dissipate as the economy grew. Even seriously lagging regions would “catch up,” the argument went, as business ideas diffused and cost differentials motivated people and firms to relocate to lowercost regions. For years, the facts stood on the side of economic theory. Until 1980, the wage gap between places was shrinking.

But the emergence of new economic forces— globalization and technological change—along with relatively recent regulatory and policy changes have weakened the dynamics that once favored regional convergence. The prosperity generated in the new economy has failed to lift up all regions. Today, some places are the beneficiaries of economic change while others are its victims. Or, as the University of California, Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti has summarized, prosperity is now accumulating in a handful of cities with the “right” industries and pools of well-educated workers. By contrast, cities and towns at the other extreme, the ones with the “wrong industries and a limited human capital base,” are stuck with dead-end jobs and low average wages. The result is a distinct geography of growth and decline that challenges the longstanding, mainstream economic assumption of regional convergence.

What does this troubled new geography look like? Depictions of wage and employment data show several problems. Public policy professors Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, for their part, have displayed a dramatic decline of income convergence across states in the years since 1940; they see a breakdown of the incentives for particular migration paths that would otherwise promote convergence.

For our part, we see a significant parallel change across cities since 1969.5 Whereas a robust “convergence” or “catch up” to the national average of employment and wages in lower-ranking places was apparent through much of the 20th century, the pattern dissipates in the 1980s and, in fact, has reversed in the years since then, according to our analysis of metropolitan-area wage data.

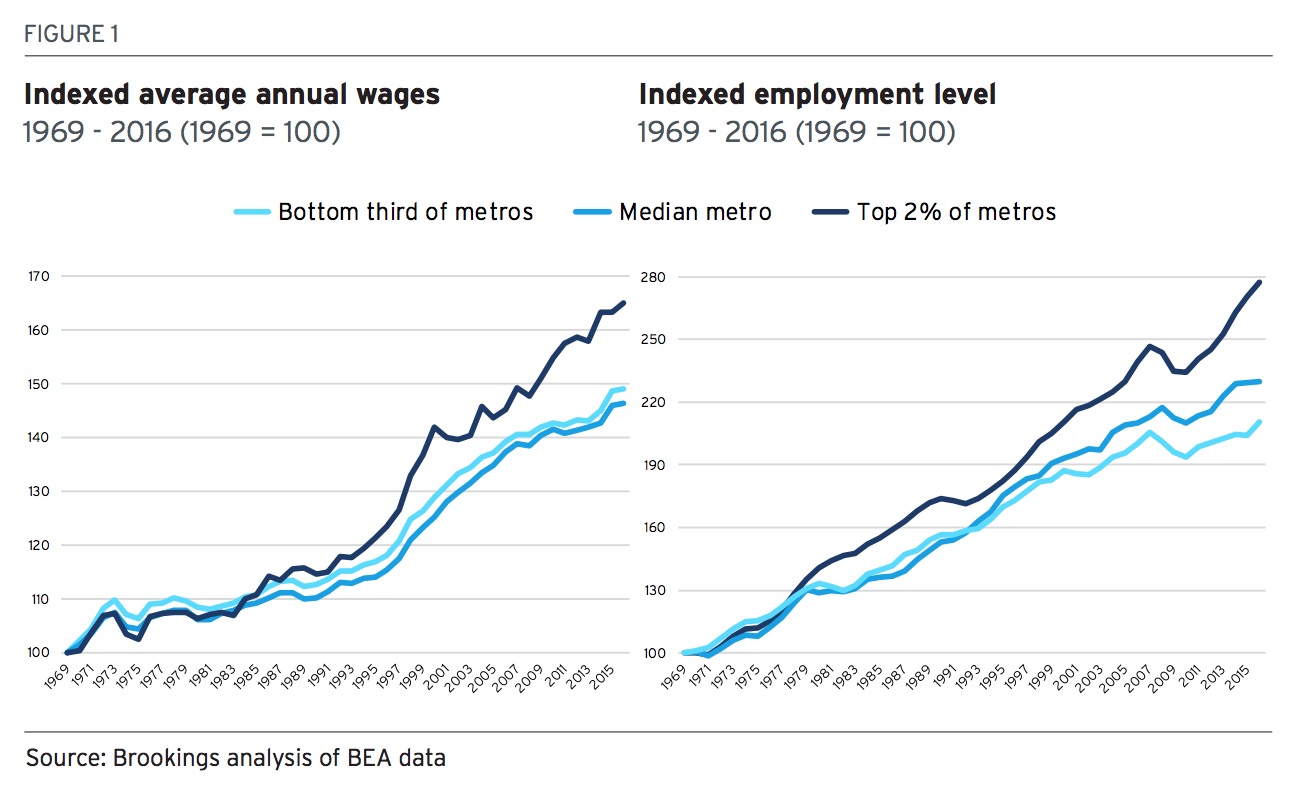

From 1969 to the mid-1980s, as is visible below, the average annual wage and employment changes of the bottom third of metropolitan areas, of the median metro, and of the top 2 percent of metros basically all track together. In many of these years the bottom third of cities actually saw faster wage and employment growth than the other groups, meaning that convergence was occurring.

Then the pattern changes. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the wages and employment of the uppermost set of metropolitan areas begin to consistently grow faster than the median and least prosperous cities. By the late 1990s, this group of metros—which includes cities such as San Jose, San Francisco, New York, Boston, and Washington, DC—began to see their wages and employment increase much faster than those of the median metro. Since then, after a pause in the mid-2000s, the cohort of “superstar” cities has been surging, pulling farther away from the median and trailing metros.

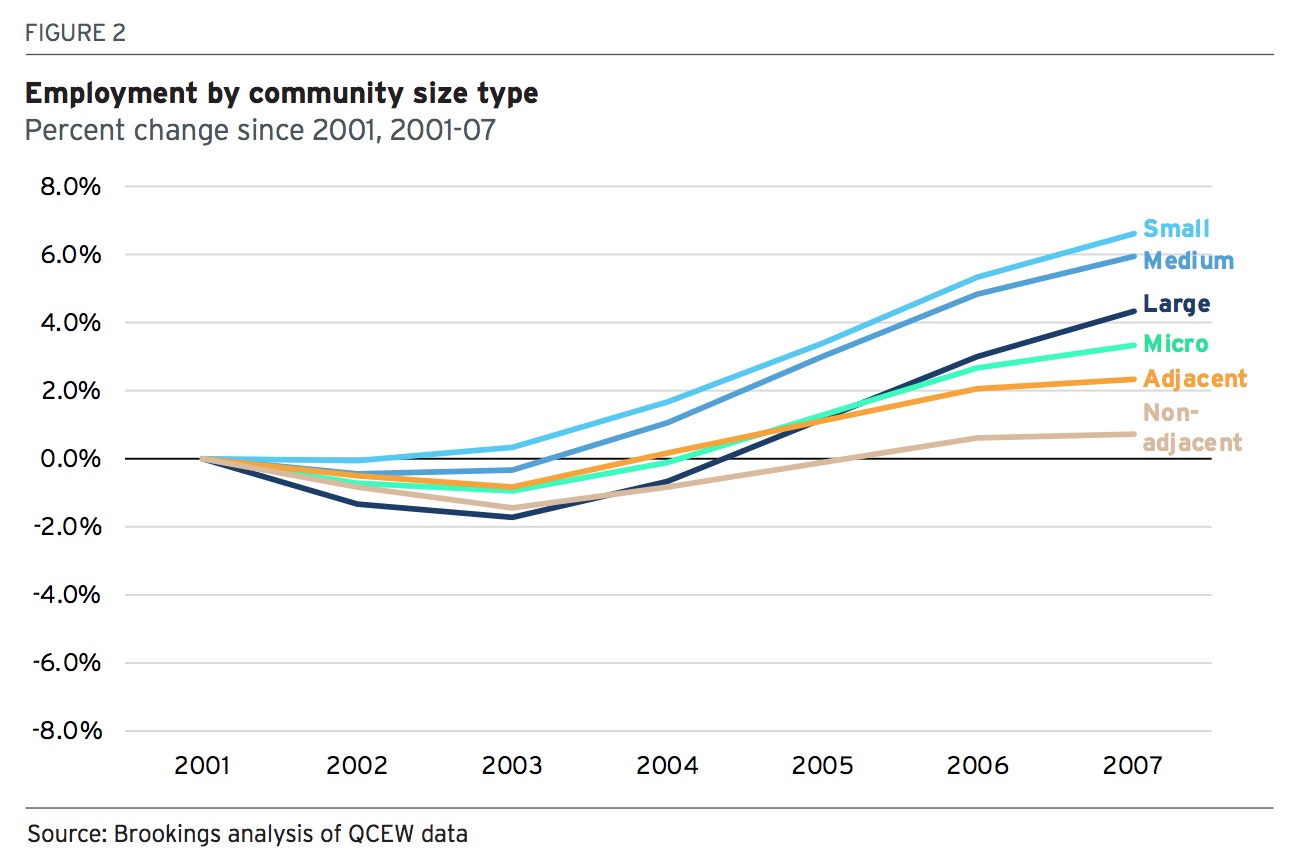

The story has not only revolved around the divergence of cities. It has also entailed a narrowing of the types of places that now dominate the “club” of winners. In this decade, especially, the widening adoption of digital technologies has contributed to a pronounced tilt toward big, populous places. Take a look at employment growth since 2000 as it occurred in large metros with populations over 1 million; middle-sized metros with populations between 250,000 and 1 million; small metros with populations between 50,000 and 250,000; “micropolitan” towns with populations between 10,000 and 50,000; and then rural areas both adjacent to metro areas and not adjacent.

Initially, small- and medium-sized metropolitan areas saw the largest proportional increases in employment, as in the period from 2001-2007 before the Great Recession. During this period, micropolitan areas and rural counties adjacent to metropolitan areas also showed relatively strong growth.

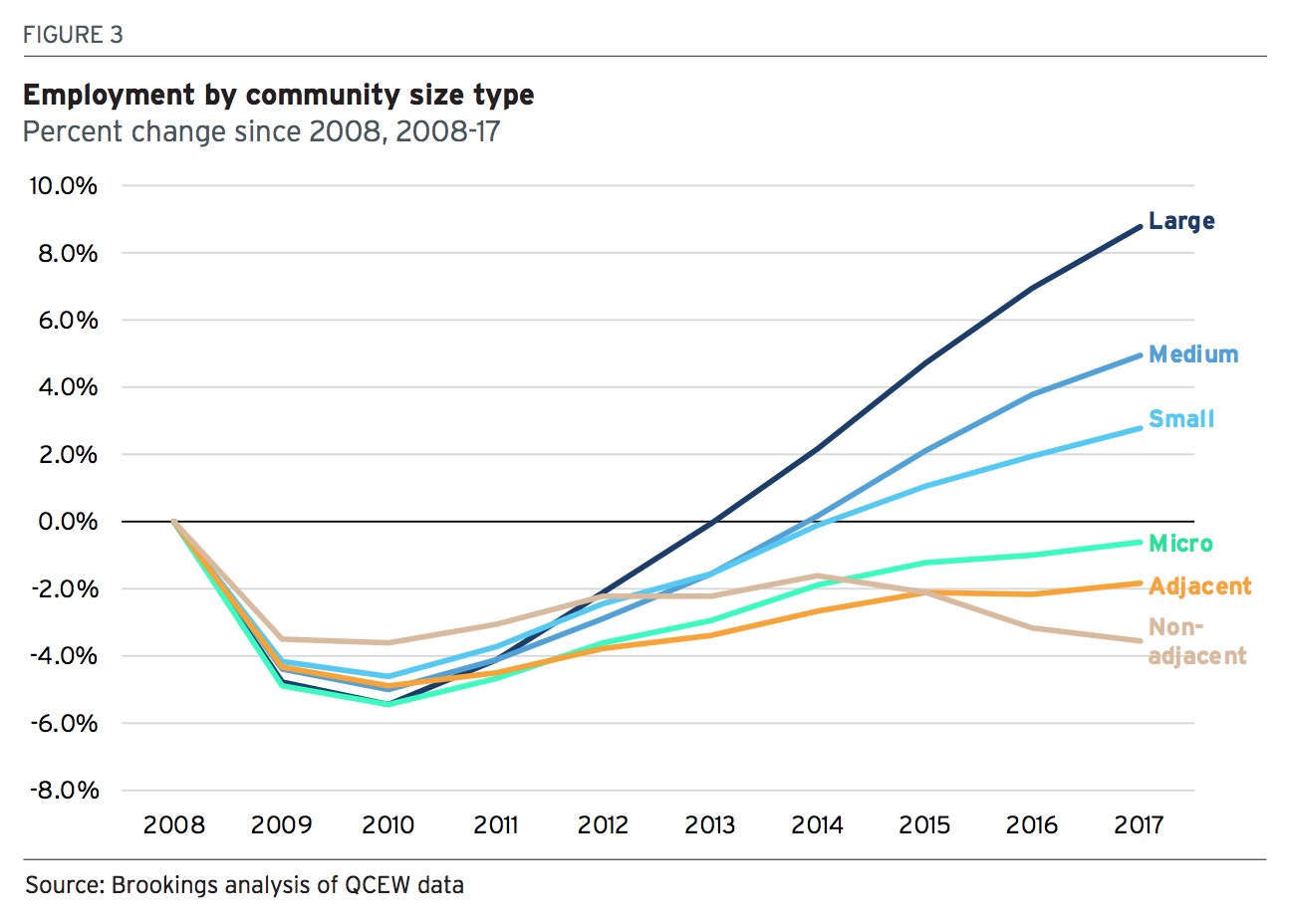

In the post-crisis period, however, a clear rank-ordered performance by community-size emerged.

On employment growth, for example, the 53 very largest metro areas (those with populations over 1 million residents) were pulling far away from the experiences of other communities. In fact, these big metros have accounted for 72 percent of the nation’s employment growth since the financial crisis, and over three-quarters of it since 2015 (though they account for just 56 percent of the overall population in that year). Mediumsized metros followed them. By contrast, smaller metropolitan areas with less than 250,000 people—representing 9 percent of the nation’s population—have lost ground. Since 2010, in fact, these scores of communities contributed less than 6 percent of the nation’s growth. As for the 1,800-plus “micro” towns and rural communities, the trends have been negative. True, the past two years show some signs of economic revival in America’s smaller places, likely driven by economic good times and the current surge of production. But overall, nearly a decade after the Great Recession, the outlook for the places that have been left behind appears dim. Employment in many non-metropolitan places remains below its pre-recession level while the longer-term patterns of growth and divergence remain troubling.

Download full version (PDF): Countering the Geography of Discontent

About the Brookings Institution

www.brookings.edu

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, DC. Our mission is to conduct in-depth research that leads to new ideas for solving problems facing society at the local, national and global level.

Tags: Brookings Institution, Rural

RSS Feed

RSS Feed