RE:FOCUS PARTNERS

Investing in resilience is complicated. Like healthcare, there are multiple strategies that can and should be combined to improve overall health. For example, there are things you can do regularly to ward off risks (preventative care), other options to address acute conditions (treatment or medical intervention), and finally actions you can take to ensure that illness doesn’t bankrupt you or those who depend on you (health and life insurance).

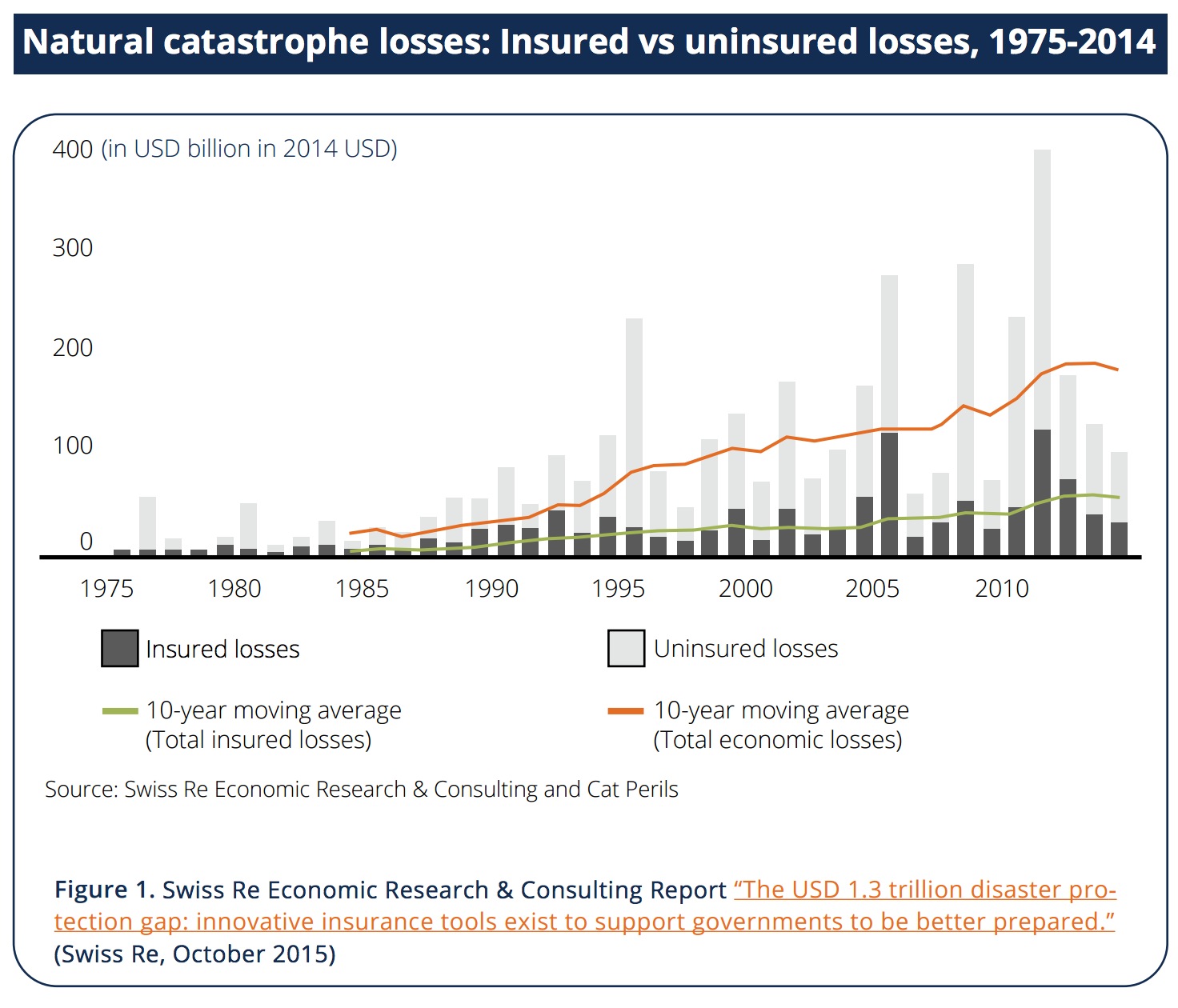

Strategies to protect communities from disasters follow a similar pattern. Projects to increase resilience—infrastructure upgrades or new protections—are designed to reduce the physical risks of damages. Once prevention is no longer an option, disaster response and recovery measures, including disaster aid and reconstruction funds, are designed to help the system recover and rebound back to health more quickly. Finally, at the far end of the spectrum, financial instruments, like catastrophe bonds, are designed to help protect those who could suffer devastating financial disruption in the event of a disaster, including owners of large assets and insurance companies. Just as life insurance doesn’t actually make you physically healthier, financial insurance instruments do not reduce physical risks. In contrast, projects designed to reduce physical risk and damages do reduce financial risks. In other words, effective on-the-ground resilience projects are designed to ensure that a severe event doesn’t become a physical or financial disaster. Despite the obvious connection that physical protections provide financial protections—a storm hits but doesn’t create massive economic losses—there are few mechanisms to connect these two different types of investments.

This paper offers a new approach for systematically linking catastrophe bonds and conventional project finance to support large-scale resilience projects. The following sections describe the RE.bound Program framework for catastrophe modeling, bond structuring, and bond sponsorship; summarize key insights and lessons for extending the approach to a range of resilience applications; and offer ideas for government and other public-interest entities seeking to build resilience and mitigate disaster risk.

The Balancing Act Between Insuring Disaster Risk and Financing Resilience

Often the most cost-effective solutions to disaster risk are the ones available to communities prior to a disaster to protect against a loss occurring in the first place. Yet cities around the world are struggling to fund even basic infrastructure projects, let alone more complex investments in resilient systems. Public cash reserves and budgets for insurance are increasingly constrained, and the capital cost of large-scale resilient infrastructure, such as coastal protection projects or flood barriers, is often too high to be absorbed by local governments or utilities. Too often the benefits are diverse, diffuse, long-term, and non-monetary, making the same types of infrastructure investments unattractive to private investors.

Despite the growing interest in investing in resilient infrastructure, the pipeline of projects remains stubbornly stuck in traditional, direct revenue models, such as toll roads and bridges, and planning for resilience upgrades and improvements remains a public sector challenge. Most of these projects, like coastal wetlands and levee systems, are viewed as public goods that generate diffuse benefits long into the future. The risks and benefits are often broader than anticipated, only appreciated in hindsight, and are rarely captured directly to support the original investment. As a result, resilient infrastructure projects are typically supported by federal, state, or local funds, and data analysis on the risk reductions is rarely done at a level of detail required to support access to capital market financing.

Like investors in energy efficiency, resilience project developers need to be able to quantify the savings from improvements before designing a financing mechanism to capture this value. For example, after decades of property-level data collection and modeling, an investor in a large-scale energy efficiency project can, with reasonable confidence, assume the risk of providing capital that is paid back through savings or benefits over time. In the case of resilience projects, the data on interventions that create measurable risk reductions are not as readily available or as easily extrapolated across projects. Everything is site and context specific; for example, a seawall reinforcement can have wildly different risk reduction profiles in different locations. This is very different from energy efficiency projects, for example, where the electricity savings from new lightbulbs are consistent across many applications.

So how can cities and communities systematically evaluate and monetize the benefits of resilient infrastructure projects as part of their overall risk management strategy? Catastrophe models and novel bond instruments offer one approach.

About Re:Focus Partners

www.refocuspartners.com

“We are social entrepreneurs with expertise in public policy and sustainable development. We design integrated resilient infrastructure systems — including water, waste, and energy projects — and develop new public-private partnerships to align public funds and leverage private investment for vulnerable communities around the world.”

Tags: Disaster, Insurance, RE:Focus Partners, Resilience

RSS Feed

RSS Feed