ACCESS MAGAZINE

Written by Mark Delucchi and Kenneth Kurani

City planners, transportation analysts, and policymakers have struggled to reconcile the promises and problems created by suburban land use and automobiles. On the one hand, automobile use and suburban living are widely and highly valued; as people become wealthier, they tend to buy cars and live in bigger homes farther away from central cities. Many urban planners, however, blame automobiles and automobile-driven sprawl for a wide range of problems, including climate change, road fatalities and injuries, rising traffic congestion, ugly urban form, oil dependency, and increasing social fragmentation. Most approaches to these problems focus on curtailing automobile use and its impacts. Outside of densely populated cities, however, it is hard to reduce personal automobile use.

In light of this, we ask if it is possible to retain automobility and low-density living alongside safe, convenient, economical, and environmentally sound transportation. We have designed an ambitious vehicle, roadway, and land-use scheme to make transportation more sustainable while preserving the personal automobile use and suburban living that many people desire.

Creating New Vehicle Classifications

Our plan constructs a dual roadway network with separate roads for low-speed, low-mass modes (LLMs) and for conventional, fast, heavy vehicles (FHVs). LLMs are distinguished from FHVs by mass and speed limits: LLMs have 1,000 lb maximum curb weight (the weight of the vehicle with fuel and fluids but not passengers or cargo) and 25 mph top speed. LLMs would include pedestrians, bicycles, pedicabs, mopeds, motor scooters, motorcycles, golf carts, and minicars. FHVs range from cars, trucks, and vans used for daily personal travel to tractor-trailers that deliver most of the goods we buy. Though conventional (i.e., not speed-regulated) motorcycles and scooters are below the mass threshold for LLMs, their capability to exceed the LLM speed limit means they would be classified as FHVs.

Differentiating vehicles by mass and speed is important, because many of the energy, environmental, safety, congestion, and land-use problems associated with motor vehicles and their infrastructure are related to kinetic energy (½mv2, where m is mass and v is velocity) of travel. In addition, vehicle mass and speed influence the kind of materials used to manufacture and design vehicles and infrastructure. Reducing vehicles’ kinetic energy will help mitigate all of these problems. For example, a speed limit of 25 mph will protect pedestrians and cyclists without sacrificing travel times for within-city trips, while the 1,000 lb weight limit still allows for practical and economically feasible small automobiles. Given these speed and mass limits, the kinetic energy of a heavy LLM traveling at its top speed is about one tenth that of a conventional passenger car traveling at 35 to 45 mph, which translates into important energy, environmental, and safety benefits.

How, then, can we dramatically reduce the kinetic energy per passenger mile of travel? LLMs could use existing roads, but it is dangerous to mix light-weight, low-speed modes with fast, heavy vehicles. Given these safety concerns, we believe that LLMs and FHVs should not share any roadway space. Instead, the conflict between providing universal access to all travelers, and the dangers of mixing FHVs and LLMs, can be resolved by giving every household, business, and public place direct access to two separated, city-wide travel networks: one for FHVs and the other for LLMs.

A Dual-Road Network

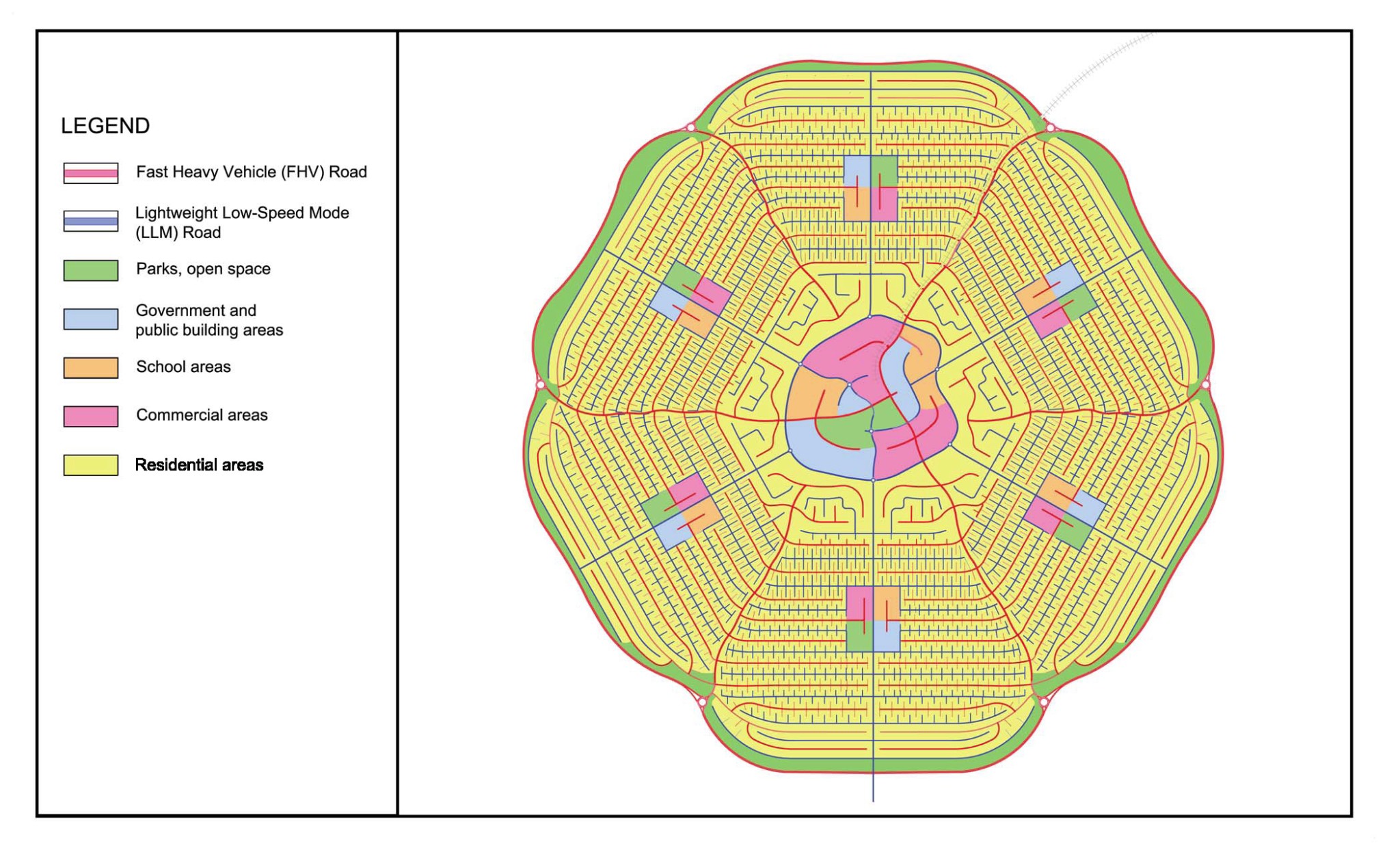

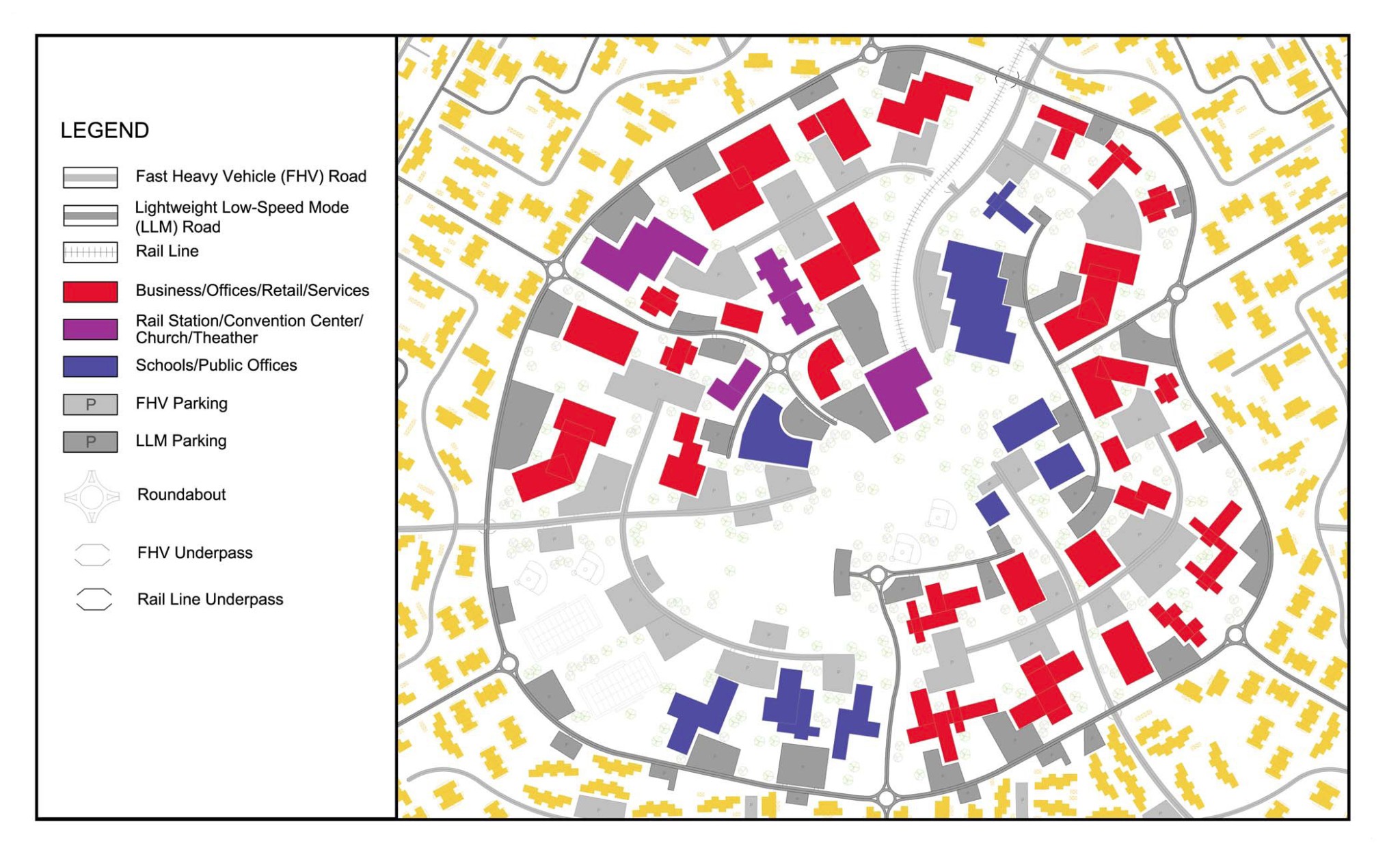

We propose a system of two citywide road networks with ring roads and interlacing radial streets (Figure 1). The two networks —LLM roads and FHV roads—serve every parcel of land but never intersect. A central LLM road encircles the town center containing shops, schools, offices, places of worship, civic buildings, inter-city transit stations, and so on (Figures 1 and 2). Radial LLM streets feed into the central ring road and provide direct, LLM-only access from all neighborhoods to the town center and other neighborhoods. Where traffic volumes are high, LLM streets can have separate lanes or paths for walking or cycling.

The entire town lies within an outer high-speed FHV beltway. The FHV roads radiate inward from the beltway, interlacing with the LLM streets. FHV roads will both provide regional connections and provide FHV access to the town center via two or three radial roads.

…

Elements of Our Plan in the Real World

Several of the ideas presented here have been implemented in actual towns or discussed in planning literature. We know of no proposed or actual plan, however, that explicitly connects kinetic energy to sustainability indicators or has the main features, scope, scale, and objectives of our plan.

Suburban planning and urban design movements have a long history, from Ebenezer Howard’s 19th century Garden City to post-1980s neo-traditional design. Some have identified problems inherent in having a single road system for all types of vehicles. Over 35 years ago, William Garrison and colleagues at UC Berkeley examined how neighborhoods and roads should be changed to accommodate small, clean, and inexpensive motor vehicles. Although they addressed many of the issues we do, and came to many similar conclusions, they did not propose a comprehensive scheme for transportation and town planning.

Many neighborhoods, and a few towns, have an extensive dedicated bicycle and pedestrian path system that is accessible to most or all homes and does not intersect with the conventional street system. Examples of these include the Village Homes neighborhood in Davis, California; the town of Radburn, New Jersey; and the town of Houten in the Netherlands. Houten, a town of about 50,000 residents near Utrecht, comes closest to what we envision. It has a dedicated bicycle network consisting of collector routes originating in residential neighborhoods and connecting to a backbone that runs to the city center. It also has a car-only network consisting of an outer ring road from which car roads penetrate into residential areas, provide limited access to the city center, and occasionally interlace with the dedicated bicycle pathways.

About ACCESS Magazine

www.accessmagazine.org

ACCESS Magazine reports on research at the University of California Center on Economic Competitiveness. The goal is to translate academic research into readable prose that is useful for policymakers and practitioners. Articles in ACCESS are intended to catapult academic research into debates about public policy, and convert knowledge into action. Authors of papers reporting on research here are solely responsible for their content. Much of the research appearing in ACCESS was sponsored by the US Department of Transportation and the California Department of Transportation, neither of which is liable for its content or use.

Tags: ACCESS Magazine, Kenneth Kurani, Mark Delucchi, Suburban, Surburbs, University of California Center on Economic Competitiveness

RSS Feed

RSS Feed