The following is a Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Policy in Public Policy

By Marissa N. Newhall, B.A.

1. Introduction

“It is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best, since you have to sweat up the hills and can coast down them. … Thus you remember them as they actually are, while in a motorcar only a high hill impresses you, and you have no such accurate remembrance of country you have driven through as you gain by riding a bicycle.”

—Ernest Hemingway (White 1967, 364)

…

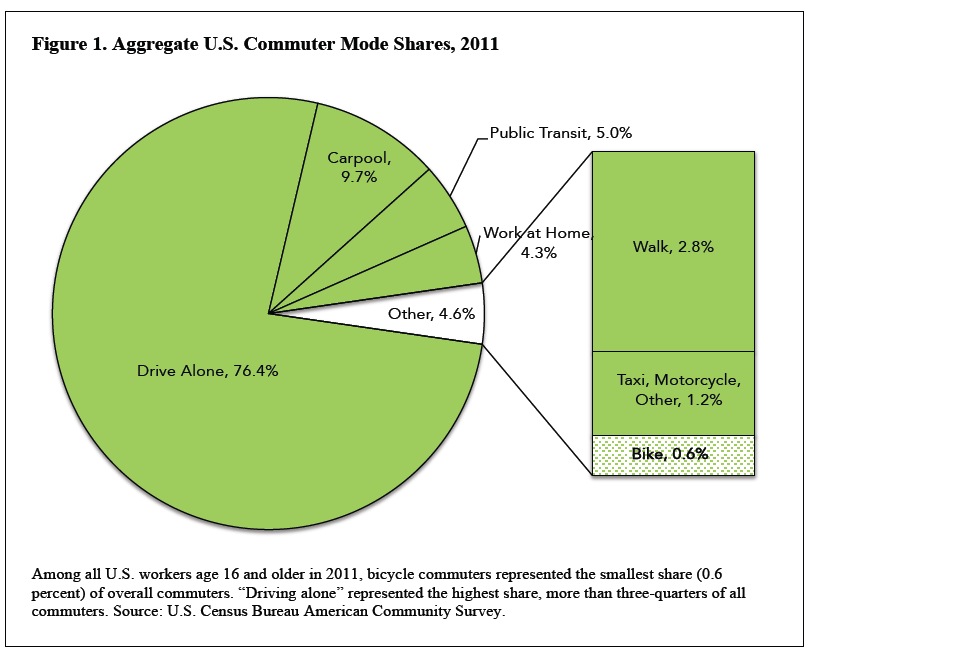

Transportation policies that promote “active commuting,” or encourage people to walk or ride bicycles to and from work and school, are becoming more popular in the United States. A closer look at some other U.S. trends helps explain why.

Obesity rates are rising. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nine states had obesity rates in excess of 30 percent in 2009, and obesity now affects 17 percent of all American children (CDC 2010 and 2012).

Traffic congestion has persisted or worsened in several major U.S. urban areas. One estimate put the cost of congestion in 2011 at $121 billion, or $818 per commuter, a $1 billion increase over 2010 (Texas A&M 2013).

Concerns about climate change are becoming more real. Transportation accounts for about a third of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions (DOT 2013), and total vehicle miles traveled continue to increase (Rodrigue 2013).

Cities are looking for creative, cost-effective solutions to these problems, and getting more people to trade car trips for bike trips seems to be a logical one. Prior studies have shown that bicycle infrastructure – e.g. signage, dedicated bike paths, on-street bike lanes, and public bikesharing programs – is positively correlated with commuter choice to bike to work (Buehler and Pucher 2011). Over the past two decades, the federal government has provided more than $8.5 billion in taxpayer-funded grants to states to build bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. But MAP-21, the most recent comprehensive surface transportation legislation, has changed the way this funding is designated, spreading a smaller pool of funds across more programs and raising questions about the federal government’s long-term commitment to funding bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure.

Given that bicycle commuting is good for people and the environment, and is favored as public policy by multiple levels of government, it is important to understand the effectiveness of policy interventions to support it, particularly in the face of uncertainty about long-term funding availability. It is clear that infrastructure funding drives the physical creation of bike lanes. But how does it affect actual commuting behavior? Does the amount of funding that the government dedicates to building bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure have an effect on individual commuters’ preference for biking to work?

To answer this question, I analyzed bicycle commuting rates as a function of federal spending on bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure in the 51 most populous cities in America in 2007, 2009, and 2011. The results show a positive, statistically significant relationship between per capita levels of federal funding and bicycle commuting rates, when controlling for other factors that would affect a city’s bicycle commuter count. Section 2 of this paper provides background on bicycle commuting in the U.S., the role of infrastructure in getting people to bike to work, and the history of federal funding for this infrastructure. Section 3 reviews the social science literature on infrastructure and bicycle commuting. Section 4 discusses basic conceptual frameworks for modeling transportation demand. Section 5 explains the data and methods use in the analysis. Section 6 presents empirical findings. Section 7 discusses the policy implications of my results and presents ideas for future research.

Download full version (PDF): Biking to Work in American Cities

RSS Feed

RSS Feed