1000 Friends of Wisconsin | Chippewa Valley Transit Alliance | CUSH | NAOMI | MICAH | ESTHER Sierra Club–John Muir Chapter | SOPHIA | Wisconsin Council of the Blind and Visually Impaired | WISDOM

Introduction

Public Transportation: A Growing Need

Mobility is a critical component of a fulfilling life; without reliable transportation, access to work, the grocery store, health care, places of worship, and social opportunities can be impossible. For those who drive personal vehicles, mobility may be taken for granted. However, a significant number of residents in Wisconsin are non-drivers. The following section outlines major categories of non-drivers:

Mobility is a critical component of a fulfilling life; without reliable transportation, access to work, the grocery store, health care, places of worship, and social opportunities can be impossible. For those who drive personal vehicles, mobility may be taken for granted. However, a significant number of residents in Wisconsin are non-drivers. The following section outlines major categories of non-drivers:

Seniors

A 2015 statement from the Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources (GWAAR) states, “[a]dults over 60 years old make up about 22% of the population in WI. In some districts, this number is as high as 30-40%. One in five Wisconsin residents aged 65 and older does not drive and will be seeking transportation options. In Wisconsin, 53% of non-drivers over the age of 65 stay isolated in their homes.” Since that statement was published, the number of Wisconsin residents over the age of 65 has increased. Projections indicate that that trend will continue, as the population of seniors is forecast to double by 2040 in most Wisconsin counties. Effective public transportation will continue to increase in importance for seniors who wish to remain independent without personal vehicles.

People with Disabilities

In addition to Wisconsin’s aging population, some Wisconsinites are unable to drive due to disability. Visual impairments, epilepsy and limited mobility are just a few examples of health conditions that may impact one’s ability to drive. More than 8 percent of Wisconsin residents ages 18-64, and 33.1 percent of those ages 65 or older, have one or more disabilities. Age or disability can contribute to social isolation and often present obstacles to reaching healthcare appointments, school, work, the grocery store and more.

Individuals with disabilities, regardless of age, face many transportation challenges. Denise Jess, a nonprofit professional in Madison and a person with a visual impairment, explains some of her experiences with transit access:

“In deciding where in the city I was going to live, transportation access, both bus and pedestrian, was a key deciding factor in where we bought our home…this neighborhood is an expensive one to live in, so the economic cost is a big trade-off. So while I have a lot of freedom and access to move about as I want to because of the buses, we pay a huge amount of property tax, and we don’t have really inexpensive grocery stores and things like that in the downtown area. The cost of living is so much higher. I think that’s a consequence for people with disabilities. You either end up living in a lower economic area and trying to figure out transportation, or if you live where the transportation might be better, but your cost of living is higher” (story collected by Sierra Club).

In addition to the economic trade-off Denise faced, she also describes the anxiety that can accompany navigating day-to-day transportation. For those who are visually impaired, audio cues on buses are necessary. If the system is down or a stop is announced too late, it can lead to a missed stop or a negative interaction with a bus driver who may be unaware of the rider’s visual impairment. People who are unable to drive have to constantly plan ahead. Denise describes her daily thought process:

“What if the cab is running late or my ride doesn’t show up? What’s my plan B, C and D? So just an enormous amount of human energy and potential gets put into that daily management of that stuff, and I think that’s really striking, you know? How much mental and emotional, let alone physical and economic, toll that takes on people.”

The bus system nonetheless provides a freedom of mobility that would otherwise be unavailable to people with disabilities. When bus routes are changed or cut due to budget decreases, people with disabilities are among those directly impacted.

People with Low or Fixed Incomes

Economic barriers also create transportation challenges. Between purchasing a car and paying for gas, maintenance, insurance and registration, the average American spends 19 percent of every dollar on transportation. However, according to Robert Bullard, as much as 40 percent of the income of the poorest residents in the United States goes toward transportation.

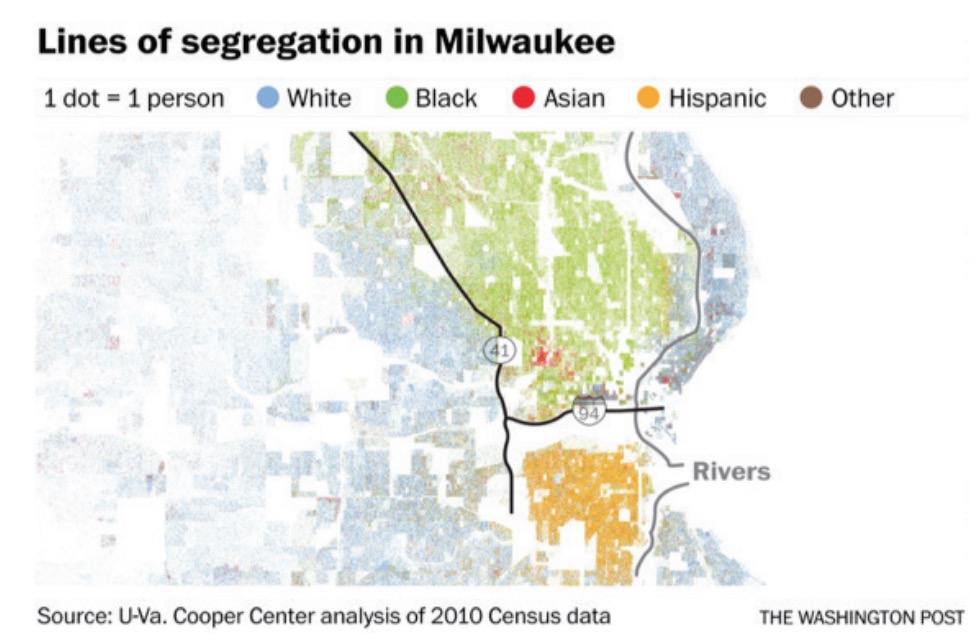

In Wisconsin, economic disparities and racial disparities are deeply connected; African American households in the state are more than three times as likely to be unemployed, five times as likely to live in poverty, and on average earn an income $27,277 lower than their white counterparts. Therefore, low income Wisconsinites, who are often People of Color, face a significant financial barrier to owning a car or to repairing their vehicle if it breaks down. Indeed, research has found that “possession of a driver’s license and a car was a stronger predictor of leaving public assistance than even a high school diploma.”

Some individuals who are unable to drive or afford a car are left without dependable transportation options, while others who live in cities with public transit options are not adequately served due to limitations of hours, number of routes or frequency of stops. Even where public transportation is available, limitations in service can disproportionately impact those who work inconsistent schedules or second and third shifts.

In Highway Robbery, Bullard writes that “[t]ransportation remains a major stumbling block for many to achieve self-sufficiency. It boils down to ‘no transportation, no job.’” In order to improve the quality of life for Wisconsin’s residents and get more people to work, connections to jobs through reliable transportation are essential.

Types of Inequity in the Transportation Sector

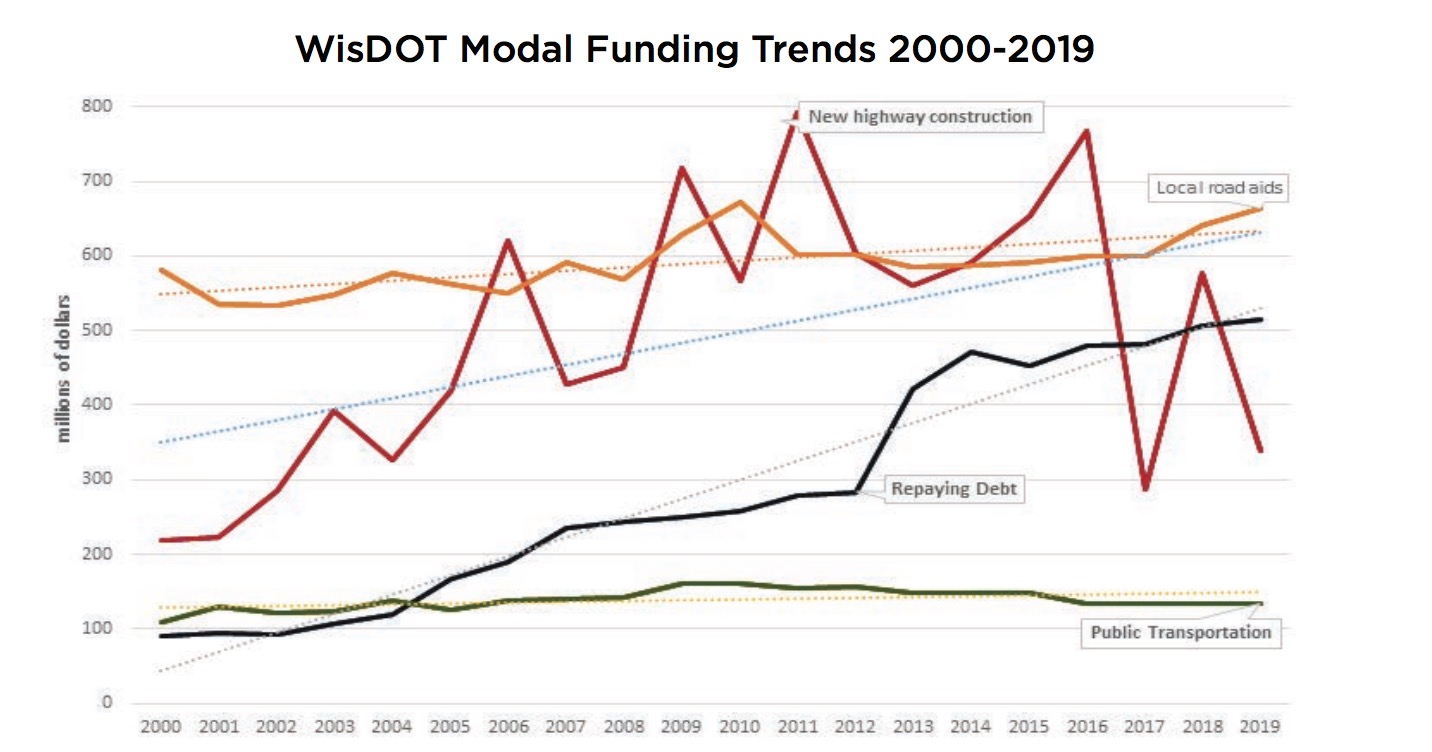

The inequities in Wisconsin’s transportation sector are easy to identify. First, the vast majority of Wisconsin’s transportation budget supports infrastructure – from interstates to major highways and local roads – that primarily benefits drivers. Because a growing portion of Wisconsin’s transportation budget is subsidized through General Purpose Revenue, debt, or local tax revenue rather than paid for through user fees like the gas tax, non-drivers bear a part of this financial burden without seeing their share of the returns.

Additionally, transit systems themselves are inequitable when the routes benefit wealthier parts of a service area over lower income areas that may have a higher percent of transit-reliant individuals. As a result, those who are already disadvantaged – whether due to age, ability or income – are further burdened by lack of transportation that connects them to their jobs, healthcare, and other essential locations.

Furthermore, low-income communities are impacted by degraded air quality due to the proximity of highways. This poor air quality negatively impacts public health and correlates with higher rates of cancer and asthma. Fifty percent of African Americans and 60 percent of Latinx people live in metropolitan areas that fail to meet national air quality standards for more than one pollutant.

Many public transportation agencies in Wisconsin are struggling to best serve their communities on shoestring budgets. Meanwhile, the state has chosen in recent decades to spend billions of dollars to add lanes to highways, with questionable justifications, that will benefit only drivers with personal vehicles. If Wisconsin wants to better serve its seniors, people with disabilities, or middle- and low-income households, state leaders must reassess Wisconsin’s transportation priorities.

Download full version (PDF): Transportation Access and Equity in Wisconsin

RSS Feed

RSS Feed