AMERICAN RIVERS

The America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report is one of the best-known and longest-lived annual reports in the environmental movement. Each year since 1984, grassroots river conservationists have teamed up with American Rivers to use the report to save their local rivers, consistently scoring policy successes that benefit these rivers and the communities through which they flow.

American Rivers reviews nominations for the America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report from river groups and concerned citizens across the country. Rivers are selected based upon the following criteria:

American Rivers reviews nominations for the America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report from river groups and concerned citizens across the country. Rivers are selected based upon the following criteria:

- A major decision (that the public can help influence) in the coming year on the proposed action

- The significance of the river to human and natural communities

- The magnitude of the threat to the river and associated communities, especially in light of a changing climate

The report highlights ten rivers whose fate will be decided in the coming year, and encourages decision-makers to do the right thing for the rivers and the communities they support.

The report is not a list of the nation’s “worst” or most polluted rivers, but rather it highlights rivers confronted by critical decisions that will determine their future.

The report presents alternatives to proposals that would damage rivers, identifies those who make the crucial decisions, and points out opportunities for the public to take action on behalf of each listed river.

The River

The Flint and Chattahoochee rivers both begin in Georgia – the Chattahoochee in the mountains north of Atlanta, and the Flint near the Atlanta airport – and they join together near the Florida border to form the Apalachicola, which flows to Apalachicola Bay. More than four million people, including 70 percent of metro Atlanta, rely on the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers for drinking water.

A powerful trio, the ACF rivers provide water for industry, power generation, agriculture, recreation and fisheries. The Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, home to the country’s first National Water Trail, attracts more than three million visitors and generates more than $290 million annually. The Flint, one of the most biologically diverse aquatic ecosystems in the Southeast, is one of only 40 rivers left in the United States that flows for more than 200 miles unimpeded by dams. Historically one of the northern hemisphere’s most productive estuaries, Apalachicola Bay once yielded more than 10 percent of the nation’s oyster harvest as well as abundant shrimp, crab and fish harvests. The ACF Basin provides 35 percent of the freshwater and nutrients to the Eastern Gulf of Mexico, supporting commercial fisheries valued at more than $5.8 billion and the livelihoods of Gulf communities and multi-generational fishing families. The basin is also home to several threatened and endangered mussels and fish including Gulf Sturgeon.

The Threat

Excessive water use, particularly in fast-growing Georgia, is the chief threat to the ACF Basin, with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ mismanagement exacerbating the problem. The upper Chattahoochee River drains one of the smallest watersheds providing water supply to a major American city (Atlanta). The Flint River’s headwaters supply water to Atlanta’s southern suburbs at great expense to property values and river health. The Army Corps, which manages multiple dams along the length of the Chattahoochee River, has been unable to reconcile Georgia’s growing water demands with needs downstream in Alabama and Florida. Across the lower basin, thousands of agricultural withdrawals from streams and the Floridan aquifer in all three states are dewatering the river system. Major lower-Flint tributaries run at low flows even in normal water years. In droughts, many run dry.

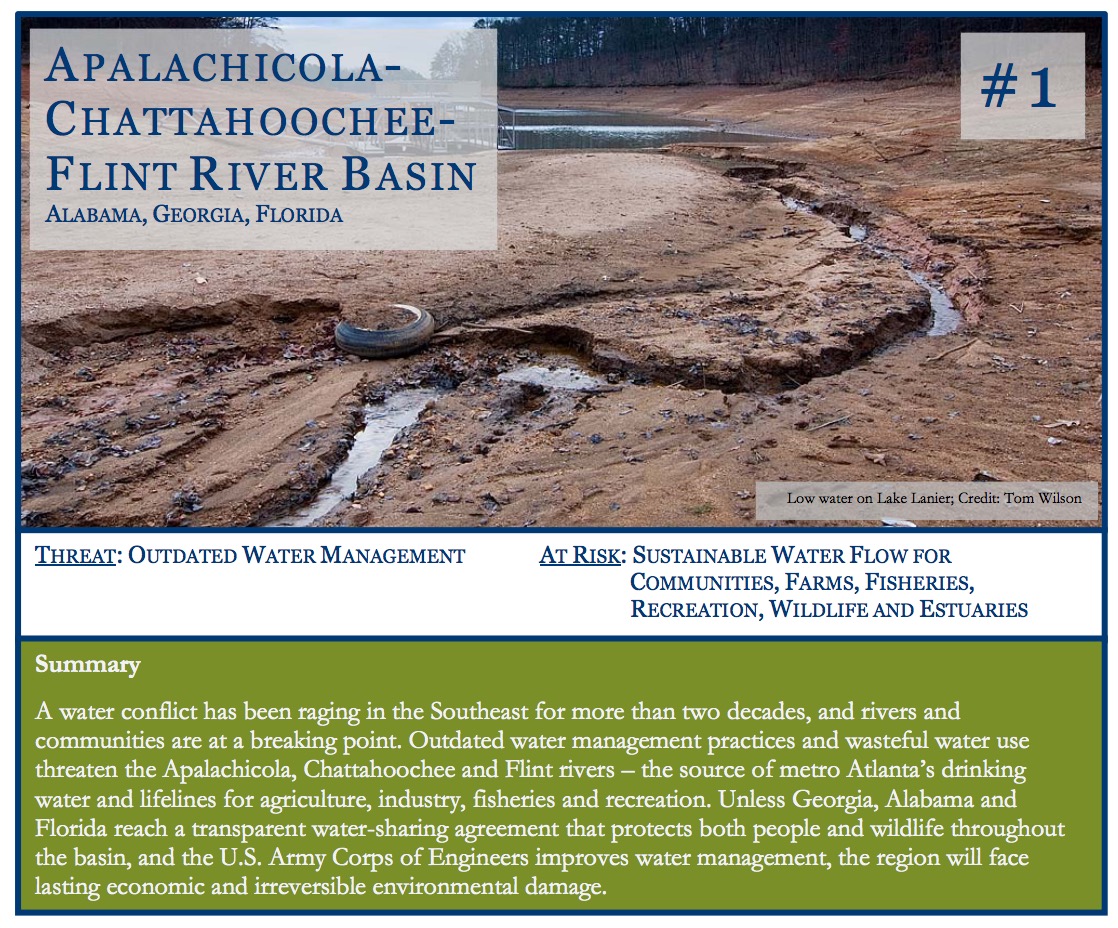

Excessive water consumption throughout the ACF Basin is having disastrous consequences for Apalachicola Bay, where oyster, crab, shrimp and fin-fish populations were decimated in 2012 and have scarcely recovered. In order to keep the Atlanta-area reservoir Lake Lanier full, the Apalachicola River’s flow is artificially held at drought levels for extended periods during dry conditions, cutting the river off from its floodplain and impacting the natural pulse of river flows and the estuary’s health. While the estuary is displaying the worst effects of over-allocation, the impacts are felt throughout the ACF Basin.

The Army Corps, Congress and the three states share responsibility for the mismanagement of water in the ACF Basin. Rather than seeking real and workable solutions, the three governors, Congressional representatives and other political leaders have been locked in litigation and political jockeying over water use for more than 25 years. The lack of a resolution to the tri-state water conflict allows status quo water mismanagement to continue. The latest legal battle is Florida’s U.S. Supreme Court suit against Georgia, putting the basin’s health and sustainability in the hands of Special Master Ralph Lancaster. Unless a negotiated settlement breaks the litigation cycle, the Special Master’s decree, for better or worse, may have long-term and unforeseeable consequences.

What Must Be Done

To address this water allocation issue in a sustainable way, Alabama, Florida and Georgia must work cooperatively to reach a water-sharing agreement that protects the rivers, floodplains and Apalachicola Bay while promoting sustainable water use basin-wide. The three governors should create a transboundary water management institution, as recommended in the ACF Stakeholders’ 2015 Sustainable Water Management Plan, to foster transparent, science-based adaptive management throughout the ACF Basin. Water conservation and wiser, more efficient water use in all sectors throughout the basin can help bring sustainability to the river system.

Additionally, the Army Corps must substantially improve water management to sustain ecosystems in the ACF Basin. Especially important is variability in flow releases from facilities managed by the Corps to maintain the health of the Apalachicola River, floodplain and bay system. The Army Corps should meaningfully involve the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and other federal and state natural resource agencies in the update and implementation of the ACF Water Control Manual. Finally, a supplemental Environmental Impact Statement is necessary in order to support the revision of the manual with up-to-date information concerning future water needs, especially in North Georgia, as well as to evaluate environmental impacts extending from the headwaters to Apalachicola Bay.

Download full version (PDF): America’s Most Endangered Rivers® 2016

About American Rivers

www.americanrivers.org

American Rivers protects wild rivers, restores damaged rivers, and conserves clean water for people and nature. Since 1973, American Rivers has protected and restored more than 150,000 miles of rivers through advocacy efforts, on-the-ground projects, and an annual America’s Most Endangered Rivers® campaign. Headquartered in Washington, DC, American Rivers has offices across the country and more than 200,000 members, supporters, and volunteers.

Tags: America's Most Endangered Rivers, American Rivers, Rivers

RSS Feed

RSS Feed