AMERICAN COUNCIL OF ENGINEERING COMPANIES (ACEC)

Public-private partnerships present opportunities and challenges for engineering firms

By Samuel Greengard

Over the last few decades, funding for public projects has declined, and public-private partnerships, also known as P3s, have gained popularity.

Over the last few decades, funding for public projects has declined, and public-private partnerships, also known as P3s, have gained popularity.

P3s are now used in 33 states and have the support of global entities such as the World Bank. “They have emerged as an attractive way to reduce public debt and shift at least some of the risk and rewards to private companies,” says David Baxter, executive director of the Institute for Public-Private Partnerships (IP3).

Today, P3s are used to build roadways, ports, airports, hospitals, water and energy facilities, university buildings and more. Proponents say this approach can dramatically reduce costs and produce better outcomes.

P3s are now widely used in the U.K., Canada, Australia, China, India, Japan, Russia and the United States. They’re also viewed as an attractive way to fund desperately needed infrastructure in developing nations.

While there’s no single definition or approach for P3s, common experience holds that they completely rewire the way projects are managed. P3s shift the burden away from government entities that contract for services and finance debt through bonds and taxes. They incorporate an arrangement that involves a private sector firm or group —the concessionaire—that raises equity and then builds and operates the project for a specified number of years. The three most common repayment mechanisms are:

• Toll Concessions, where the concessionaire receives compensation through obtaining the right to collect the tolls on a facility;

• Availability Payment Concessions, where the concessionaire receives periodic “availability” payments from the public partner based on the availability of a facility at the specified performance level; and

• Shadow Toll Concessions, where the concessionaire receives a set payment called a “shadow toll” for each vehicle that uses the facility.

However, throughout the lifespan of the project, the government entity retains ownership and control. A P3 is not privatization.

Recent passage of the $305 billion, five-year Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST), further boosts the prospects of P3s usage by establishing a National Surface Transportation and Innovative Finance Bureau. The agency aims to increasingly leverage federal dollars in transportation projects by facilitating private participation, and to encourage innovative financing mechanisms that help advance projects more quickly.

But even with growing U.S. implementation, P3s aren’t without obstacles, challenges and potential controversy. In some cases, P3s generate a higher rate of return than when the same project falls into the public sector, and if the operator fails or goes bankrupt, disruption and higher financing costs can result. There is also political opposition to toll roads and other P3 projects in some states, and there can be land-rights issues.

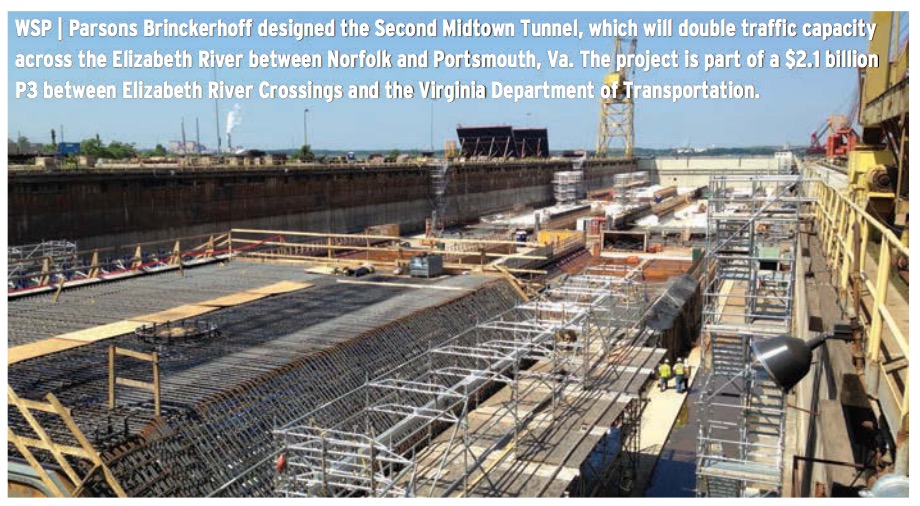

According to the National Council for Public-Private Partnerships, P3s typically lead to a 7 percent to 10 percent savings over the life of the project. In some cases, the figure can reach 20 percent or more. Not surprisingly, firms that participate in P3s must think differently, work differently and interact with partners and other project participants in entirely different ways. “There is a growing recognition of the benefits of delivering projects through this alternative delivery model. In many cases, they come to market quickly and the results are impressive,” says Sallye Perrin, a senior vice president at WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff, which has worked on P3 projects such as the Midtown Tunnel project in Virginia and the Port of Miami Tunnel. “But it isn’t something that an engineering firm can jump into. It requires expertise and an understanding of how the P3 framework operates.”

Successful P3s

The U.S. has no shortage of high-profile P3 projects, particularly in Texas, Florida and California. One of the first major uses of the P3 model in the U.S. dates back to 1999, when the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey faced a limited debt capacity to finance necessary improvements to New York’s JFK International Airport. It ultimately turned to a consortium of private developers, operators and financiers to renovate the international terminal. In addition, a private company has a 28-year lease with the Port Authority to operate the terminal.

Another P3 project, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s White Oak Campus in Maryland, is expected to save more than $200 million over 20 years. It will free up more than $90 million in capital appropriations that can instead be directed to the agency’s functional requirements. Yet, many of today’s largest P3 projects revolve around highways and rail transportation. In Denver, a new commuter transportation network, the Regional Transportation District (RTD) FasTracks, involves 122 miles of light rail and 18 miles of bus transit service. As part of the program, the $2.3 billion Eagle P3, which began in 2010 and is scheduled for completion this year, is estimated to save about $300 million over the transportation network’s lifespan. In Texas, the LBJ express lanes project—which is rolling out in three phases—has tapped an international group to finance, design, construct, operate and maintain a 13-mile freeway corridor on Interstate 635 for 52 years. Among the innovative features the project offers: dynamic toll pricing based on traffic volumes. The P3 approach has allowed TxDOT to build a $2.7 billion project in a five-county area that was otherwise budgeted for $171 million. It will increase traffic volumes from a system designed to carry 180,000 vehicles per day to one that will accommodate 500,000 in 2020.

Called the LBJ TEXpress Lanes, the project has so far moved forward ahead of schedule and without any significant change orders. “It is one of a growing number of success stories,” Perrin says. “As these projects take shape and roll out, it’s becoming apparent that they offer a viable alternative to public financing. In many cases, they move forward faster, at a lower cost, and deliver better technical designs.”

Called the LBJ TEXpress Lanes, the project has so far moved forward ahead of schedule and without any significant change orders. “It is one of a growing number of success stories,” Perrin says. “As these projects take shape and roll out, it’s becoming apparent that they offer a viable alternative to public financing. In many cases, they move forward faster, at a lower cost, and deliver better technical designs.”

Despite glowing examples of success, not all projects fare so well. In 2014, the operator of the 157-mile Indiana Toll Road—a partnership between the Spanish firm Ferrovial S.A. and the Australian firm Macquarie Infrastructure Group—filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy after projected traffic volumes and revenues failed to materialize. The state took over management of the highway. Three years earlier, in Southern California, the operators of the $635 million South Bay Expressway in San Diego County declared bankruptcy.

“There are risks and concerns for engineering and construction firms related to contractual relationships with concessionaires and others,” says John Muñoz, a vice president for CDM Smith and a former deputy director at TxDOT.

Download full article (PDF): Navigating the P3 Landscape

About the American Council of Engineering Companies

About the American Council of Engineering Companies

www.acec.org

The American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC) is the voice of America’s engineering industry. Council members – numbering more than 5,000 firms representing more than 500,000 employees throughout the country – are engaged in a wide range of engineering works that propel the nation’s economy, and enhance and safeguard America’s quality of life. These works allow Americans to drink clean water, enjoy a healthy life, take advantage of new technologies, and travel safely and efficiently. The Council’s mission is to contribute to America’s prosperity and welfare by advancing the business interests of member firms.

Tags: ACEC, American Council of Engineering Companies, Engineering Inc., P3, P3s, Public-Private Partnerships, Samuel Greengard

RSS Feed

RSS Feed