RAND Corporation

Imagine yourself in 2050, the first year in which not a single person in America died in a traffic crash.

Imagine yourself in 2050, the first year in which not a single person in America died in a traffic crash.

How can that be? The United States’ population has exceeded 400 million. The demand for mobility has increased with the population and improved access to transportation, especially for groups that previously had limited mobility options.

It’s thanks to some amazing strides we’ve made since the 2010s in several different areas. Nearly all vehicles, including motorcycles, now have high levels of vehicle automation, whether they are self-driving or human-driven. Almost all cars now brake automatically, warn drivers about objects in their blind spots, park themselves, adjust their speed, and stay in their lanes. While crashes still happen, there are many fewer of them.

In 2050, those crashes are less severe, in part because of changes to how we build roads. Roadways are designed to reduce speed in safety-critical areas and lessen the chances of the most severe crash types, such as head-on collisions, while allowing faster travel in areas that are safer and where there are few potential conflicts among vehicles or between vehicles and pedestrians or cyclists. Over the past decades, planners and engineers have prioritized changes to the highest-risk roads, which are identified by collecting and analyzing detailed data.

Roadway design has also evolved, becoming entirely performance-based, resulting in more-innovative configurations leading to improved safety. Techniques that are routine in 2050 include physical separation of opposing traffic lanes, safer pavements that eliminate edge drop-offs, and surfaces that help prevent skidding. The United States has been using these techniques to build new roads and redesign or retrofit existing ones for several decades now, allowing vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians to share the road more safely.

Remote rural roads are still more hazardous—they always have been—but safety technologies are particularly effective in preventing the most dangerous rural crashes, such as head-on collisions and single-vehicle run-off-the-road crashes. Safety on rural roads, where emergency response times are higher than on city streets, has been further enhanced by improvements in trauma care, including increased investment in emergency response, together with enhanced connectivity for faster crash notification, improved injury prediction, better communication with 911 and first responders, and more-effective emergency medical care.

Improvements in digital infrastructure in rural areas, together with widespread adoption of vehicle-to-vehicle communication, have also meant reductions in crashes, because vehicles can share safety information with one another and with their environment and use this information to avoid collisions. Although the safety gap between rural and urban areas has not quite closed, thanks to technology, it is narrower now than ever.

The safety effects of these changes have been extended by policies and practices that protect the most-vulnerable road users and incentivize safe driving and adoption of advanced safety technology. Reducing speeds in cities has helped reduce pedestrian and cyclist deaths. Insurance companies have incentivized use of automated vehicles, especially by high-risk drivers. Some cities and companies that manage a variety of mobility options through a single account—“mobility services”—have made it easy to get around without having to drive, and they have been early adopters of advanced safety technology.

A wide variety of groups involved with traffic safety committed to implementing evidence-based safety measures and began adopting a “Safe System” approach in the first decades of the 21st century. This turned the traditional thinking about safety on its head—instead of seeing humans as the offenders, responsible for most crashes because of their bad habits, planners and engineers began thinking that the system itself needs to be safe.

Given that it’s impossible to eliminate human error entirely, planners and engineers began thinking of ways to design roads and vehicles to accommodate human error to make the entire system safer. This was paired with efforts toward creating a “safety culture” that emphasizes the value of safety in every decision made by every person. Safety has become a shared responsibility among those who use the system and those who design and operate the system. A whole generation is now using these approaches.

In 2050, businesses are investing in safety and sharing in the benefits of healthier employees and a more supportive community. Innovative finance methods, such as social impact bonds that pay investors for positive outcomes, have created opportunities for large-scale renewal and improvement projects. Other forms of public-private collaborations—not unlike the push for electrification of rural areas in the early 20th century—have helped upgrade safety in rural areas.

As the number of crashes began to fall, individual attitudes about road safety and personal responsibility changed substantially. In much the same way that people changed their minds about alcohol-impaired driving in the 1980s and 1990s, drivers in 2050 feel that their communities expect them to comply with speed limits and to not drive distracted. Widespread community road-safety action programs have connected individuals with the larger movement and resulted in a further dramatic advance in norms and social expectations—for example, that nobody drives impaired and everybody wears a seat belt.

Eliminating roadway deaths has lifted Americans’ quality of life in very obvious ways. On an individual level, parents no longer worry about teens driving, adults don’t fret about “taking the keys away” from an aging mom or dad, and people going home after a night on the town call an automated vehicle to drive them home. On the broader level, the financial effects and time savings are considerable. In 2010, it was estimated that crashes cost the U.S economy roughly $835 billion, and there were 15,000 crashes per day. Now, 40 years later, police and emergency responders can shift attention to other needs, states and insurance companies can spend less on medical expenses, and the federal government can spend less on disability payments. Reaching zero fatalities on our roadways is a crusade that was once thought quixotic, but it’s the world of 2050.

Why Zero? Is This Really Possible?

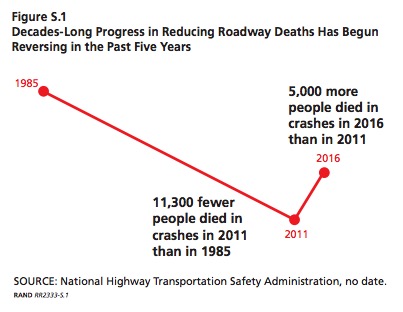

Back in the world of 2018, the idea of a future with literally zero roadway deaths seems like a pipe dream. Roadway deaths—deaths due to traffic crashes—have been increasing, not decreasing, over the past two years. In 2016, more than 37,000 Americans died on the roads— 5,000 more people than died in 2011.

The United States has made good progress in road safety over the long run, despite this recent backsliding, but incremental progress is no longer acceptable given the increasingly rapid advances in technology and the wealth of knowledge about how to prevent crashes. Inspired by the goals and progress in other countries, the broader traffic safety community is now working together to achieve a common vision—that by 2050, nobody would be killed in a traffic crash on U.S. roads.

Why zero? That raises the question, “What level of death on the roads should we as a society accept?” How many of our own family members, classmates, neighbors, or people in our community losing their lives to crashes would be considered an appropriate number? These deaths are preventable—the safety community deliberately calls them crashes, not accidents, for this very reason. Accident implies unforeseeable circumstances or a twist of fate, but crashes can be prevented. The number of roadway deaths has long been accepted as a “price” of mobility, but 37,000 deaths is more than 100 Americans killed per day. Imagine the outcry if plane crashes or natural disasters killed 100 Americans every day.

As to whether this is possible, the country has seen enormous improvements in safety in other areas. As of 2017, no commercial U.S. airline passenger flight has had a fatal crash since 2009, thanks in large part to a collaborative government/industry safety management system. The number of people who smoke has fallen by more than half in 50 years, thanks to education campaigns and laws limiting where people can smoke.

In addition, the experiences of other high-income countries show that more-significant change is feasible. In 2013, the U.S. roadway death rate was more than twice the average of other high-income countries, and almost all of those countries have seen greater improvement than the United States over the past two decades. Sweden, where the idea of Vision Zero began, has seen declines in its crash death rates of 50 percent or more, using the Safe System approach. A number of U.S. cities and states have also embraced this Vision Zero strategy.

While it will take a generation, the success of other countries and some U.S. cities demonstrates that a combination of approaches makes this an achievable goal.

The Urgency: Roadway Deaths Are Moving in the Wrong Direction

The more than 37,000 people killed in crashes in 2016 represent a troubling reversal in previous progress. For the past several decades, all the important measures of roadway deaths—the total number, the number per population, the number per miles driven—were going down as a result of several factors, including changes in driving patterns, increased seat belt use, improvements in vehicle design, more-forgiving roadway designs, and stronger graduated driver’s license programs for teen drivers. After reaching an all-time low in 2011, these trends began reversing in 2015, and got even worse in 2016. Figure S.1. shows the extent of the problem.

We Know Who Is Dying and Why

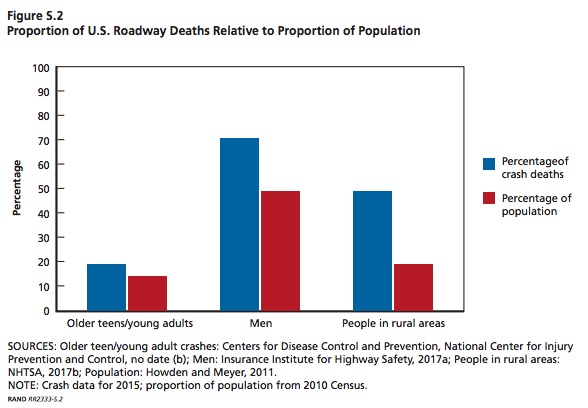

Who dies on U.S. roads, and why? While crashes affect every state, type of road user, and demographic group, three groups are more frequently affected than others:

- Young people are affected disproportionately, as crashes are the leading cause of death for people age 15 to 24. Because so many victims are young, crashes are also a leading cause of years of life lost—that is, the number of years people would have lived had they not died of an illness or injury. Crash risks for teen drivers are higher than for any other age group.

- Men die more often in crashes than women, in all categories of crashes; 71 percent of people killed in crashes are men. By crash type, the percentage of fatalities that are men ranges from 49 percent of car passenger deaths to 99 percent of large truck deaths.

- Rural road users are disproportionately affected as well. In 2015, an estimated 19 percent of the U.S. population lived in rural areas, yet almost half of roadway deaths occurred on rural roads. Rural roads are more dangerous than urban ones; for the same number of miles driven, more than twice as many people die in rural areas.

While not a demographic category, pedestrian risk has increased dramatically in recent years. Of the 5,000 more people who died in motor vehicle crashes in 2016 than in 2011, 1,500 were pedestrians. In 2015, pedestrian deaths accounted for 15 percent of all traffic fatalities, and about three-quarters of pedestrian deaths occurred in urban areas.

In terms of why, we can classify the reasons that people die in car crashes in three ways:

What causes the crash: Crashes stem from many factors. A main one is that current vehicle and roadway designs require that drivers be constantly alert and vigilant. However, drivers predictably become distracted, inattentive, tired, or otherwise impaired. This misalignment between human behavior and system design underlies the great majority of fatal crashes.

Who survives the crash: Many factors determine crash survival. The presence and use of safety features in cars—seat belts, airbags, improved door locks, and many others— are responsible for saving tens of thousands of lives each year. Roadside safety hardware, such as breakaway sign poles and smoother redirecting guardrails, makes crash outcomes less severe. Occupants that buckle up are more likely to survive crashes. Motorcycle helmets save lives as well. Speed is also an important factor in surviving a crash, whether inside or outside the vehicle—the lower the speed, the less severe the outcomes.

Who gets medical treatment: Of all crash fatalities, about half survive the initial crash but later die from their injuries. Enhanced emergency medical personnel capabilities, use of a medical helicopter, and reaching an appropriate trauma center can improve crash survival.

We Know How to Reduce Roadway Deaths

The substantial improvements in road safety that the United States has seen over the past several decades can be attributed to many factors. One is better vehicle technologies developed by automakers, better in terms of avoiding crashes and protecting those in the vehicle—such technologies save 27,000 lives every year. Technologies such as airbags and electronic stability control are already standard, but advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), such as automatic emergency braking, blind spot monitoring, and lane departure warning, are being offered on more and more vehicles.

Another factor involves the ways in which roads are designed and constructed to increase road safety. In more-rural areas, these include designs for roadsides that reduce the number of obstacles that cars would strike if they run off the roads, pavements that reduce skidding, and increased use of rumble strips, crash cushions, and guardrails. In more-urban areas, they include designs for urban intersections that reduce the speed of turning cars, broad use of roundabouts to bring down vehicle speeds in intersections, and shorter pedestrian crossing distances that make it safer and easier for people to cross busy streets.

Credit is also due to a wide range of safety experts: engineers, researchers, and public safety and public health professionals who have garnered extensive evidence on which countermeasures are most effective. Strong leadership from safety-minded policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels has resulted in the adoption of laws, regulations, and funding for effective policies. Examples of effective policies include increasing the minimum drinking age from 18 to 21 years old and reducing the legal blood alcohol level to 0.08 percent. When coupled with education and enforcement, such policies cut the number of alcohol-impaired driving deaths by half. The enactment and enforcement of mandatory seat belt use laws in nearly every state have increased seat belt use from less than 20 percent to 90 percent.

Further safety gains can be made with current safety approaches, as some of the most effective policies have not been used to their full potential. However, with 260 million registered vehicles, 215 million drivers, 4 million miles of roads, and steadily increasing annual vehicle mileage, the cumulative risk on U.S. roadways will outpace past and current countermeasures unless we double down on our efforts.

In recent years, more attention has been given to two fundamental concepts, safety culture and the Safe System approach. Safety culture is the broad set of attitudes and beliefs that underlie people’s decisions. Safety culture affects judgment about priorities in individual behavior and support for collective decisions about what is most important in our communities. Getting to zero deaths will involve countless individual and collective decisions, and a strong safety culture is an essential prerequisite.

The Safe System approach is integral to the Vision Zero movement that started in Sweden in the 1990s and began spreading to the United States a decade later. Vision Zero begins with a commitment to focus on the changes necessary to eliminate roadway deaths rather than being satisfied with incremental progress, and goes on to include the creation of a transportation system that accommodates predictable human error without resulting in roadway deaths.

In the United States, the Toward Zero Deaths National Strategy was launched in 2014, adopting the zero-focused imperative along with a strong commitment to creating a safety culture, and the strategy has since been adopted by many states. More recently, a number of U.S. cities have adopted the Vision Zero approach with particular dedication to building a Safe System.

Both the safety culture and Safe System movements are potentially powerful tools for achieving the changes needed to reach zero roadway deaths.

Download full version (PDF): The Road to Zero

About RAND Corporation

www.rand.org

The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest.

Tags: Crashes, RAND Corporation, Road to Zero, Roadway Deaths, Safe System, safety, safety culture, Toward Zero Deaths National Strategy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed