UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY OFFICE

America’s rail transportation infrastructure, including its passenger rail system, requires substantial repair as well as new capacity to accommodate growth. In April 2016, the Northeast Corridor (NEC) Infrastructure and Operations Advisory Commission estimated that a minimum of $28 billion is needed to address repair backlogs on the NEC—one of the busiest rail corridors in the world. Amtrak has also estimated that an additional $151 billion in capital investments will be needed for state of good repair and to enhance capacity on the NEC. In addition, proposed high-speed rail projects in California, Texas, and Florida as well as the restoration and redevelopment of passenger rail stations, such as those planned for New York City, will require billions of dollars.Is

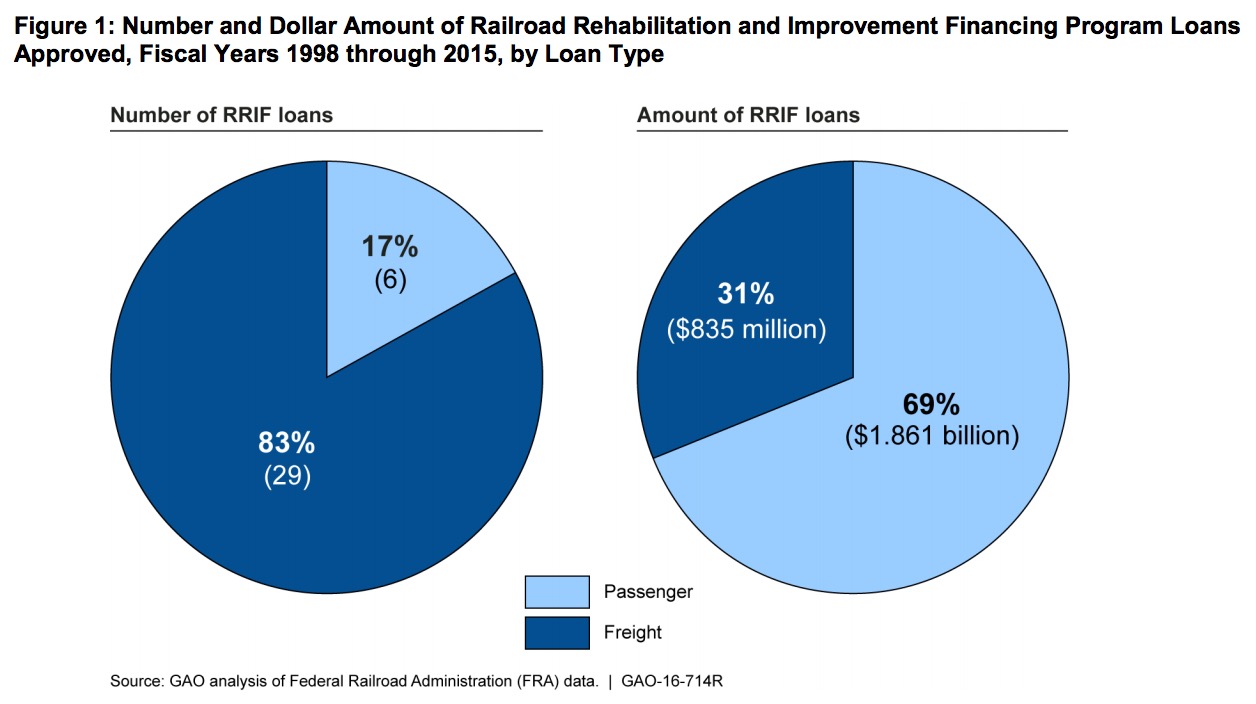

Financing the various rail infrastructure projects will be challenging. Congress has not funded the Federal Railroad Administration’s (FRA) High-Speed Intercity Passenger Rail program—a program used to fund passenger rail projects—since fiscal year 2010 and appropriations to Amtrak have remained relatively steady at about $1.4 billion over the last 5 years. One potential source of funding is FRA’s Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) program, which is a $35 billion loan and loan guarantee program to finance, among other things, freight and passenger rail facilities. Since program inception in 1998 about $2.7 billion in loans have been executed, and no loan guarantees have been made.

The Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act made a number of changes to the RRIF program intended to increase use of the program. Section 11611 of the FAST Act includes a provision for the Government Accountability Office to transmit a report within 180 days of enactment that analyzes how the RRIF program can be used to improve passenger rail infrastructure.

This report presents information on: (1) the changes made by the FAST Act to FRA’s RRIF program and the status of implementing these changes; (2) views of selected stakeholders about the potential impacts of these changes on the RRIF program, particularly in terms of types of projects financed, potential sources of repayments, and overall use of the program; and (3) views of selected stakeholders on the advantages and disadvantages of using the RRIF program for financing passenger-rail infrastructure projects as compared to other sources of financing.

To address changes made by the FAST Act to the RRIF program and the status of implementing these changes, we reviewed provisions of the FAST Act and other statutes pertaining to the RRIF program and interviewed FRA officials. We also reviewed past studies of the RRIF program prepared by the Congressional Research Service, the National Cooperative Rail Research Program, and the Department of Transportation (DOT) Office of Inspector General (OIG), among others, and collected historical information from FRA on RRIF program loans and program costs, including credit risk premiums.3 We also interviewed officials with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). To obtain selected stakeholders’ views about the potential impacts of the FAST Act on the RRIF program, we selected four passenger rail projects to review. They represent a mix of project size, geographic location, project development status, potential use of the RRIF program for project financing, and the potential for transit oriented development (TOD).4 Projects selected for review were: Gateway (New York/New Jersey), Chicago Union Station (Chicago), Transbay Transit Center (San Francisco), and Denver Union Station (Denver). For these projects, we interviewed public and private stakeholders, such as city governments, transit agencies, Amtrak, commuter rail agencies, and private development firms. To obtain selected stakeholders’ views on the advantages and disadvantages of using the RRIF program for financing passenger rail infrastructure projects, we interviewed stakeholders for the four projects we selected, as well as FRA and OMB officials. Finally, we interviewed other stakeholders, such as credit rating agencies, financial consultants, and a major bank that had been involved with federal credit programs. A total of 19 stakeholders were interviewed. The results of our work are not generalizable to the universe of stakeholders that have participated or may participate in the RRIF program. See enclosure I for a description of the projects we reviewed and enclosure II for a list of organizations we contacted.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2016 to July 2016 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Results in Brief

The FAST Act made a number of significant changes to the RRIF program, but FRA and DOT are still in the early stages of implementing these changes. DOT officials said they are still assessing how to implement the changes through updated guidance and standard-operating procedures. FRA officials said that they do not have a comprehensive implementation timeline because some aspects of their implementation are contingent on how DOT structures the National Surface Transportation and Innovative Finance Bureau (Finance Bureau)—a new body created by the FAST Act that will be responsible for administering RRIF and other DOT credit programs, among other things.

Stakeholders we spoke to said that changes in the RRIF program could increase demand for RRIF loans, especially for large passenger rail projects. Expansion of the program to include a broad definition of joint ventures and TOD creates potentially new alternative revenue streams to finance multi-billion-dollar station redevelopment. Stakeholders also said that realizing the potential for new investment brought about by the changes to the RRIF program will depend on how FRA implements the changes.

Stakeholders we spoke to identified advantages and disadvantages of using the RRIF program to finance passenger rail infrastructure projects compared with other financing options. Low interest rates and long, flexible repayment terms were among the advantages most often cited by stakeholders we interviewed. In general, loan interest-rate determinations and loan repayment terms are similar for both RRIF and the Transportation Infrastructure Financing and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loan programs.5 However, the requirement for the applicant to pay a credit risk premium and long or uncertain application review time frames were among the disadvantages most often cited by stakeholders. The TIFIA program, in contrast to RRIF, uses federal appropriations to pay the costs to the government of providing financial assistance.

In commenting on this report, the DOT’s Assistant Secretary for Administration said that the department valued the stakeholders’ views cited in the report and was committed to implementing the FAST Act amendments to the RRIF program in a manner that increases use of the program. He further noted that DOT is working to gain loan-processing efficiencies by aligning RRIF processes with those of other DOT credit programs and that RRIF program consolidation into the Finance Bureau (called Build America Bureau by DOT) will serve to enhance those efficiencies.

About the United States Government Accountability Office

www.gao.gov

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress. Often called the “congressional watchdog,” GAO investigates how the federal government spends taxpayer dollars.

Tags: FAST Act, Federal Railroad Administration, FRA, RRIF, U.S. GAO, United States Government Accountability Office

RSS Feed

RSS Feed