BROOKINGS INSTITUTION

METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM

Rooftop solar is booming in U.S. cities.

One of the most exciting infrastructure developments within metropolitan America, the installation of over a million solar photovoltaic (PV) systems in recent years, represents nothing less than a breakthrough for urban sustainability — and the climate.

Prices for solar panels have fallen dramatically. Residential solar installations surged by 66 percent between 2014 and 2015 helping to ensure that solar accounted for 30 percent of all new U.S. electric generating capacity. And for that matter, recent analyses conclude that the cost of residential solar is often comparable to the average price of power on the utility grid, a threshold known as grid parity.

So, what’s not to like? Rooftop solar is a total winner, right?

Well, not quite: The spread of rooftop solar has raised tricky issues for utilities and the public utilities commissions (PUCs) that regulate them.

Specifically, the proliferation of rooftop solar installations is challenging the traditional utility business model by altering the relationship of household and utility—and not just by reducing electricity sales. In this respect, the solar boom has prompted significant debates in states like New York and California about the best rates and policies to ensure that state utility rules and rates provide a way for distributed solar to flourish even as utilities are rewarded for meeting customer demands. Increasingly, this ferment is leading to thoughtful dialogues aimed at devising new forms of policy and rate design that can—as in New York—encourage distributed energy resources (DERs) while allowing for distribution utilities to adapt to the new era.

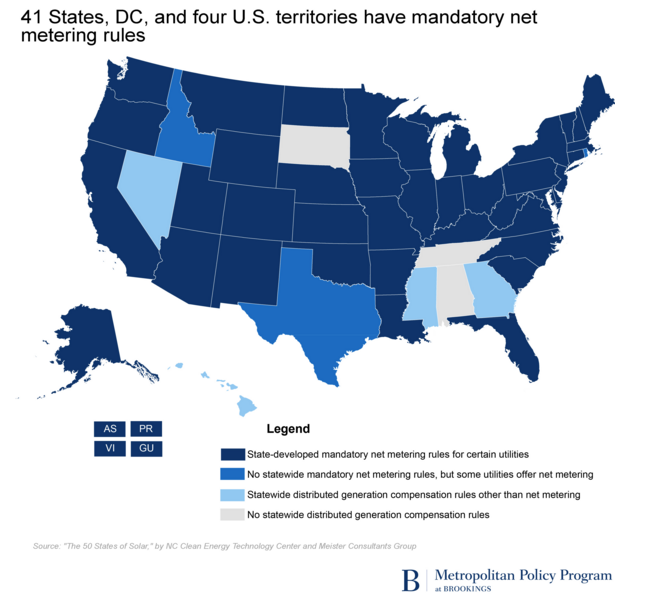

However, in some states, the ferment has prompted a cruder set of backlashes. Most pointedly, some utilities contend that the “net-metering” fees paid to homeowners with rooftop installations for excess solar power they send back to the grid unfairly transfer costs to the utilities and their non-solar customers.

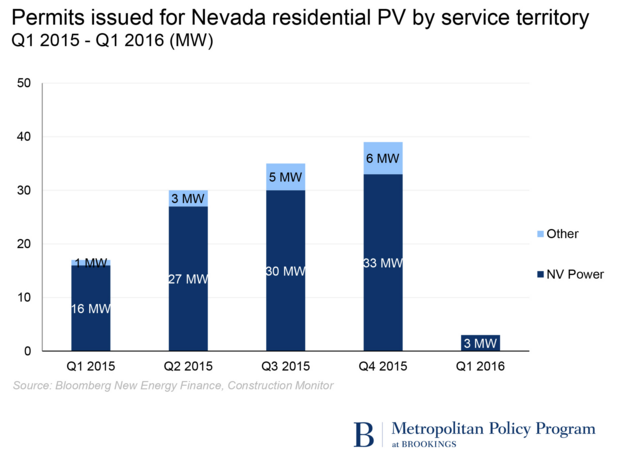

And so in a number of states, utility interests have sought to persuade state regulators to roll back net-metering provisions, arguing they are a net cost to the overall electricity system. Most glaringly, the local utility in Nevada successfully wielded the cost-shift theory last winter to get the Nevada Public Utilities Commission to drastically curtail the state’s net-metering payments, prompting Solar City, Sunrun, and Vivint Solar—the state’s three largest providers of rooftop panels—to leave the Nevada market entirely. The result: New residential solar installation permits plunged 92 percent in Nevada in the first quarter of 2016.

And so in a number of states, utility interests have sought to persuade state regulators to roll back net-metering provisions, arguing they are a net cost to the overall electricity system. Most glaringly, the local utility in Nevada successfully wielded the cost-shift theory last winter to get the Nevada Public Utilities Commission to drastically curtail the state’s net-metering payments, prompting Solar City, Sunrun, and Vivint Solar—the state’s three largest providers of rooftop panels—to leave the Nevada market entirely. The result: New residential solar installation permits plunged 92 percent in Nevada in the first quarter of 2016.

All of which highlights a burning question for the present and future of rooftop solar: Does net metering really represent a net cost shift from solar-owning households to others? Or does it in fact contribute net benefits to the grid, utilities, and other ratepayer groups when all costs and benefits are factored in? As to the answer, it’s getting clearer (even if it’s not unanimous). Net metering — contra the Nevada decision — frequently benefits all ratepayers when all costs and benefits are accounted for, which is a finding state public utility commissions, or PUCs, need to take seriously as the fight over net metering rages in states like Arizona, California, and Nevada. Regulators everywhere need to put in place processes that fairly consider the full range of benefits (as well as costs) of net metering as well as other policies as they set and update the policies, regulations, and tariffs that will play a critical role in determining the extent to which the distributed solar industry continues to grow.

Fortunately, such cost-benefit analyses have become an important feature of state rate-setting processes and offer important guidance to states like Nevada. So what does the accumulating national literature on costs and benefits of net metering say? Increasingly it concludes— whether conducted by PUCs, national labs, or academics — that the economic benefits of net metering actually outweigh the costs and impose no significant cost increase for non-solar customers. Far from a net cost, net metering is in most cases a net benefit—for the utility and for non-solar rate-payers.

Of course, there are legitimate cost-recovery issues associated with net metering, and they vary from market to market. Moreover, getting to a good rate design, which is essential for both utility revenues and the growth of distributed generation, is undeniably complicated. If rates go too far in the direction of “volumetric energy charges”—charging customers based on energy use—utilities could have trouble recovering costs when distributed energy sources reach higher levels of penetration. On the other hand, if rates lean more towards fixed charges—not dependent on usage—it may reduce incentives for customers to consider solar and other distributed generation technologies.

Moreover, cost-benefit assessments can vary due to differences in valuation approach and methodology, leading to inconsistent outcomes. For instance, a Louisiana Public Utility Commission study last year found that that state’s net-metering customers do not pay the full cost of service and are subsidized by other ratepayers. How that squares with other states’ analyses is hard to parse.

Download full version (PDF): Rooftop solar: Net metering is a net benefit

About the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program

www.brookings.edu/about/programs/metro

The Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings is redefining the challenges facing metropolitan America and identifying assets and promoting innovative solutions to help communities grow in more productive, inclusive, and sustainable ways.

Tags: Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program, Net Metering, Solar, Solar Energy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed