MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE

I. Introduction

Why people choose to travel by private car rather than by public transit is of major concern to transportation planners and transit operators. For some reluctant would-be riders, the answer might be summed up by the words of Yogi Berra when asked why he no longer patronized a popular St. Louis nightspot: “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

Passenger crowding on rail transit and in stations may not only decrease the attractiveness of transit for potential riders, it can also create unsafe conditions in stations as passengers risk being pushed onto tracks. Passengers forced to occupy space intended as a buffer along the platform edge are placed in harm’s way. Moreover, excessive station crowding can also prevent passengers from entering and exiting transit vehicles quickly and safely. If passenger volumes are so high that flow through stations is significantly obstructed, emergency evacuations may be impeded as well, risking health and safety. Beyond safety, crowding in transit stations can also reduce average vehicle speeds (and hence system capacity) by increasing vehicle dwell times due to protracted passenger boarding and alighting.

Rail is the highest-capacity transit mode, and rail transit stations frequently experience high levels of pedestrian congestion, typically during the morning and afternoon rush hours, but also related to special events – such as festivals, parades, and sporting events – that attract large crowds of riders. Occasionally, extreme events such as natural or human-made disasters, such as an earthquake, fire, or terrorist attack that require the complete evacuation of transit facilities, may also result in high levels of pedestrian congestion.

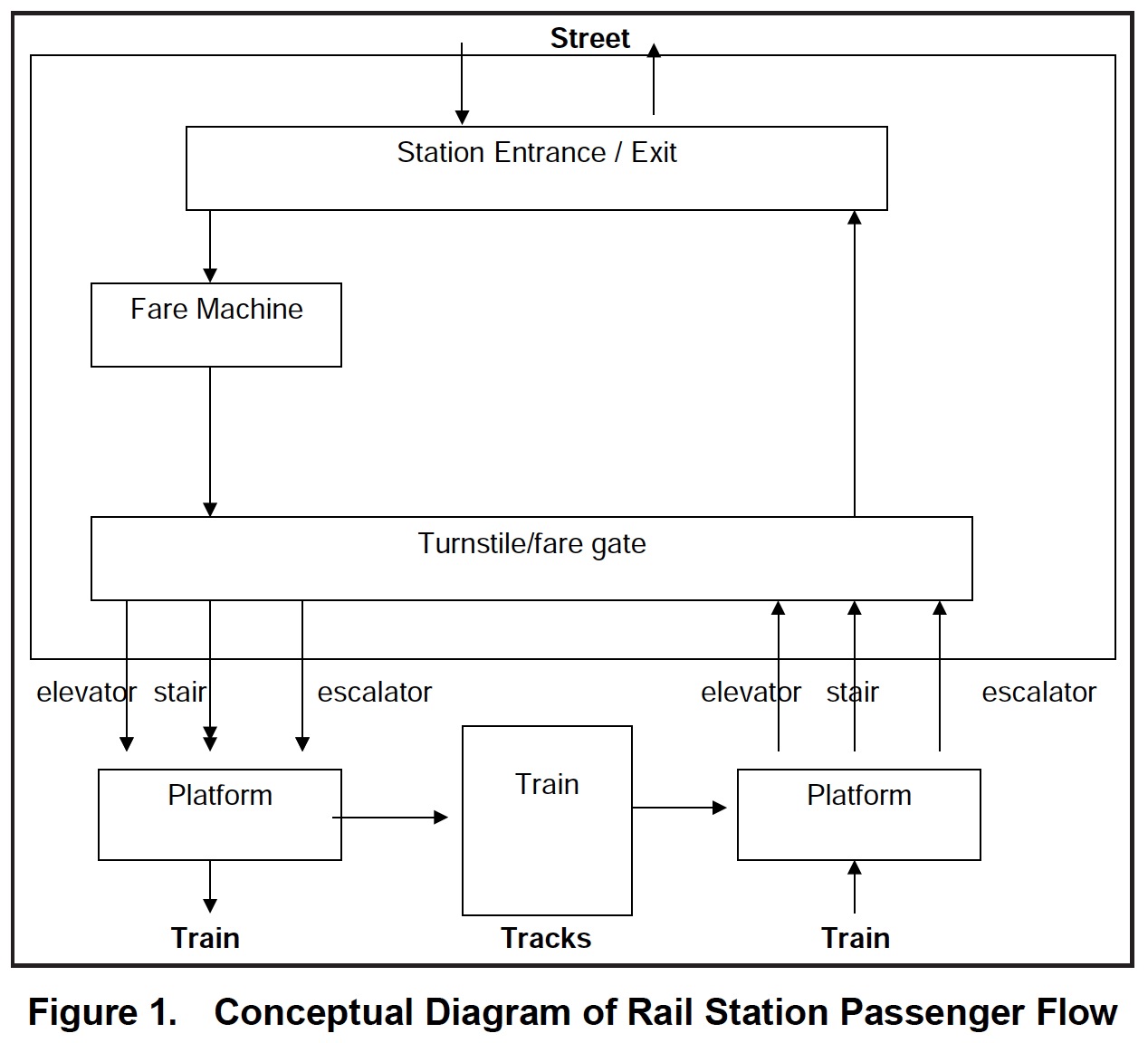

In addition to walking and waiting, passengers also frequently purchase and validate their tickets, buy newspapers or food from concessions, ask for information at kiosks, or stop to consult maps. Thus, transit station congestion can take place in walking areas such as stairways, escalators, and elevators, but also in waiting areas such as platforms (especially during train boarding and alighting times). Point areas (Figure 1) such as station entrances and exits, ticketing machines, turnstiles/fare gates, and concessions may also experience congestion and queuing. Figure 1 does not and cannot reflect the variety of station configurations that exist in underground rail stations, but it does indicate an approximate sequence of events that passengers might experience.

While there is a substantial body of literature on solutions to the technical and computational problems associated with accurately portraying the movement of pedestrians, very little has been written about how these increasingly sophisticated methods are applied in practice and the context in which they are used. Some scholars have written about the use of ridership forecasts to justify new rail transit service, and a smaller number have written about institutional and political factors that influence transit fare policy and technology adoption, but this work does not address how these phenomena affect station design. This report seeks to address these gaps in the literature.

Pedestrian flow is defined as the number of pedestrians who pass through a cross-section of an area during a given time period. (Refer to Section III for a more detailed discussion of the relationship between flow rates and related measures of speed and density.) Pedestrian flow in rail transit stations is affected by both the numbers of pedestrians sharing the space and the spatial layout of the station – including the size and location of different station areas, how these areas are connected to one another, and the number, size, and location of the vertical circulation elements (escalators, elevators, and stairs). The maximum rate of pedestrian flow is usually constrained by the acceptable levels of passenger comfort as well as by safety considerations. How transit system managers design and operate rail transit stations for optimal passenger flow and comfort is the focus of this study.

Download full version (PDF): Passenger Flows in Underground Railway Stations and Platforms

About the Mineta Transportation Institute

transweb.sjsu.edu

The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) conducts research, education, and information and technology transfer, focusing on multimodal surface transportation policy and management issues. It was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under TEA-21 and again under SAFETEA-LU. The Institute is funded by Congress through the US Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Research and Innovative Technology Administration, by the California Legislature through the Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by other public and private grants and donations, including grants from the US Department of Homeland Security.

Tags: Metro, Mineta Transportation Institute, San Jose State University, Subway, Underground

RSS Feed

RSS Feed