NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH SCIENCES

Introduction

Car use is the dominant mode of transport to work in many high-income cities. In car-oriented cities, commuting by private motor vehicle allows access to employment and training (crucial social determinants of health) while enabling households to manage competing responsibilities. However, car-dependent commuting has significant negative public health effects for commuters, the wider community, and local and global ecosystems. A mode shift to greater use of active transport would bring environmental, health, social, and equity benefits (de Nazelle et al. 2011; Hosking et al. 2011). In high-income cities, car commutes tend to be short, habitual, solitary trips in congested traffic. Consequently, they make a greater contribution to road traffic injury (Bhalla et al. 2007), air pollution and transport greenhouse gas emissions (André and Rapone 2009), noise (Hänninen and Knol 2011), and stress (Jansen et al. 2003) than other kinds of light vehicle trips. Traffic congestion at peak commute times is also a significant influence on constructing new road capacity with land use, environmental, and social costs (Coffin 2007; Fahrig 2003). In addition, the predictability of car commuting routes may make these trips amenable to a wider range of policy alternatives.

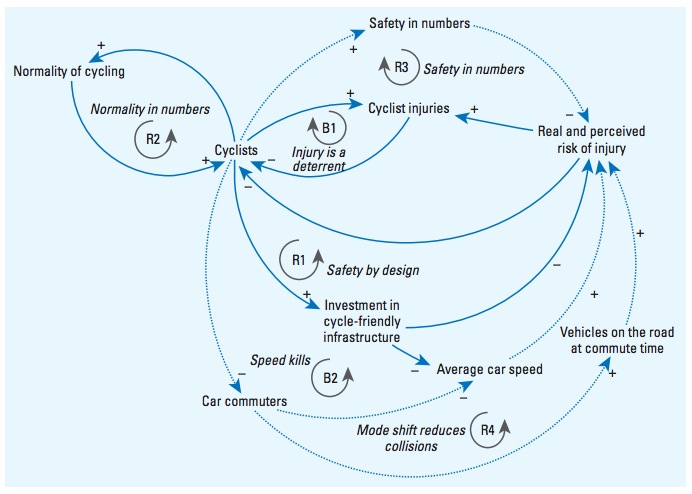

Previous integrated health impact assessments, based on existing evidence, suggest that a shift to human-powered transport modes (bicycling, walking, running, wheelchair, skating) for short commute trips would be good for health, aside from the risk of road traffic injury (Hosking et al. 2011; Woodcock et al. 2009). These trips incur negligible greenhouse gas and air pollution costs, incorporate physical activity into people’s daily lives, and cost little (potentially increasing equitable access to jobs) (Hosking et al. 2011). Although transport policy is identified as a determinant of the global noncommunicable disease (NCD) crisis, transport interventions have not been included in the United Nations’ priority actions for NCDs because of poor evidence of cost-effectiveness (Beaglehole et al. 2011). Previous comparative risk assessments have been undertaken for transport policy, climate change, and health (e.g., Lindsay et al. 2011/a>; Rojas-Rueda et al. 2011; Woodcock et al. 2009). However, these assessments have been unable to directly compare specific policies seeking to increase active transport, and have not incorporated recognized system feedbacks (Woodcock et al. 2009).

The relationships between urban planning and health are complex, and evidence for them varies widely in source and quality. Furthermore, policies may trade gains made against some objectives at the expense of others. However, a set of methodological recommendations is emerging in the literature that might promote effective policy decisions in such complex systems. They include a systems approach; transdisciplinarity (integrating knowledge across policy, community, and the academy); community participation in decision making; and a focus on social justice and environmental sustainability (Charron 2012). There have been recent calls for complex systems research to tackle deep-seated problems such as physical inactivity (Kohl et al. 2012), obesity (Swinburn et al. 2011), and improving the contribution of urban planning to health (Rydin et al. 2012).

We used the principles above to develop a commuter cycling and public health model integrating physical, social, and environmental well-being. We used this model to identify cost-effective transport policies for improving public health. Auckland, New Zealand’s largest and fastest growing city (population ~ 1.5 million), was the case study.

A program of motorway development and low-density urban growth in Auckland has led to exponential growth in car ownership and use, with a collapse in use of public transport and bicycling as modes of transport (Mees 2010). Private motor vehicles are used for > 75% of commutes, and bicycles 1%. Recently, Auckland’s regional government has been promoting bicycling for transport to reduce motor vehicle use.

Download full version (PDF): The Societal Costs and Benefits of Commuter Bicycling

About the National Institute of Environmental Health Science

www.niehs.nih.gov

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), located in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, is one of 27 research institutes and centers that comprise the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The mission of the NIEHS is to discover how the environment affects people in order to promote healthier lives.

Tags: Bicycling, Cycling, EHP, Environmental Health Perspectives, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute of Health, NIEH, NIH

RSS Feed

RSS Feed