TOULAN SCHOOL OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING, PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

Tara Goddarda, Kimberly Barsamian Kahnb, and Arlie Adkins

1. Introduction

In the United States, racial minorities are disproportionately represented in pedestrian

In the United States, racial minorities are disproportionately represented in pedestrian

fatalities. From 2000 to 2010, the pedestrian fatality rates for Black and Hispanic men (3.93 and

3.73 per 100,000 population) were twice the rate for White men (1.78), according to the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Minority pedestrians are more likely to be killed in a

motor vehicle crash even after controlling for increased traffic exposure in urban areas,

socioeconomic status, and alcohol use (CDC, 2013). One potential and unexplored contributing

factor to these disparate outcomes is whether driver behavior differs toward pedestrians by race.

Similar to other types of intergroup interactions, roadway interactions between drivers and

pedestrians are likely influenced by drivers’ subtle racial attitudes and biases.

The current study focuses on pedestrians’ street crossings, as pedestrians are most

vulnerable when crossing traffic lanes. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration, 60 percent or more of pedestrian fatalities occur during street crossings

(NHTSA, 2003). Marked crosswalks at unsignalized intersections or at midblock draw drivers’

attention to the possible presence of crossing pedestrians; however, they have also been shown to

give pedestrians a false sense of safety that may increase risk exposure (Zegeer, 2005).

Understanding driver-pedestrian interactions at crosswalks is therefore key to addressing the

public safety issues that result from the shared use of road space.

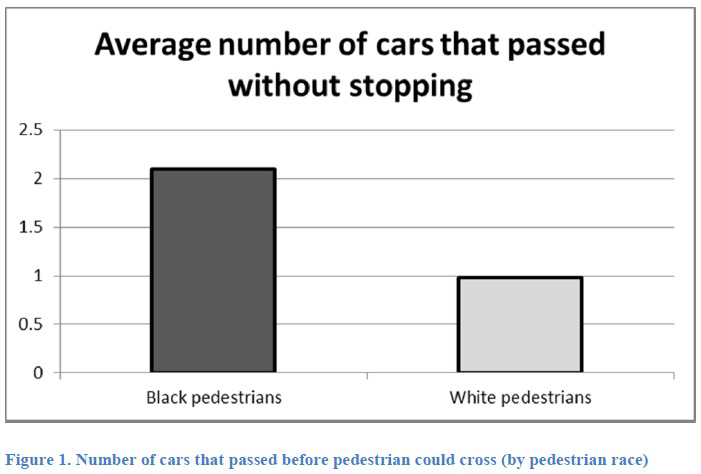

This research investigates whether driver behavior toward pedestrians in crosswalks is

influenced by the race of the crossing pedestrian. We utilized a controlled field experiment in

which we observed how drivers’ stopping behavior differed depending on whether a White or

Black pedestrian (trained members of the research team) was attempting to cross at a marked

crosswalk. Results are based on analysis of whether the first approaching car stopped, how many cars passed before the confederate could cross, and the time a pedestrian had to wait before

crossing. We hypothesized that drivers are less likely to stop for Black pedestrians than for

White pedestrians crossing at a marked crosswalk and that Black pedestrians have longer wait

times before they can safely cross. Differences in minority pedestrians’ experiences at

crosswalks may lead to more delay, increased risk, and lower quality pedestrian experiences,

leading minority pedestrians to adopt unsafe crossing behaviors and dissuading them from

choosing active transportation modes. These findings have implications for crosswalk design

and may help inform efforts to promote equitable access to active transportation within minority

communities.

1.1 The role of social identity characteristics in driver-pedestrian interactions

Drivers do not treat all pedestrians the same on the road. Different social identity characteristics of both the driver and pedestrian have been shown to influence drivers’ yielding behavior at crosswalks. Visibly identifying some pedestrians as disabled by equipping them with a cane resulted in more frequent driver yielding, fewer cars passing without yielding, and shorter wait times (Harrell, 1992). In a study of Israeli drivers, drivers were more likely to yield to pedestrians in their own age group (Rosenbloom, Nemrodov, & Ben, 2006). Driver’s socio-economic status, indicated by vehicle type, influenced whether a driver would yield to pedestrians, with drivers of high-status cars less likely to yield to pedestrians (Piff, Stancato, Mendoza-Denton, Keltner, & Coteb, 2012). These results suggest that drivers’ perceive yielding to pedestrians as a courtesy or granting of privilege, rather than an observance of rights as is often the case by law. This perceived discretionary choice may be differentially made depending on the social identity of pedestrians.

The current experiment tests whether racial group membership is one such social identity that influences drivers’ stopping behavior for pedestrians. Racial minorities are subjected to racially biased treatment and outcomes across a variety of societal domains, including education (Steele, 2010), employment (Pager, 2003; Schwartzman, 1997; Wilson, 1996), health care (Budrys, 2010; Dovidio, Penner, Albrecht, Norton, Gaertner, & Shelton, 2008), and criminal sentencing (Blair & Chapleau, 2004; Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns, & Johnson, 2006). Racially-biased behaviors are also reflected in interpersonal interracial interactions, as subtle stereotypes influence individuals’ judgments and decisions (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; Richeson & Shelton, 2007). We posited that racially biased treatment is also reflected in intermodal interactions within the transportation arena, particularly in driver’s behavior toward pedestrians.

If drivers demonstrate racially-biased behaviors, these behaviors may reflect implicit racial attitudes. While explicitly (conscious and freely expressed forms of racial bias) biased attitudes have decreased over the last 50 years (Bobo, 1991), contemporary forms of racial bias are often demonstrated on a covert or implicit level (Dovidio, 2001; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009; Olson & Fazio, 2003). Implicit racial biases are subtle, biased beliefs that individuals hold beneath their conscious awareness, but that can lead to discriminatory behavior and outcomes. Pro-White, Anti-Black implicit attitudes are commonly held by a large percentage of Americans and have been shown to be a cause of discriminatory outcomes against minorities in society (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995; Banaji & Greenwald, 2013, see also Project Implicit). Implicit bias influences decisions that are harder to monitor and more difficult to control, and are particularly influential in fast paced situations. Implicit bias has been shown to affect split-second decisions regarding safety-related behavior, exposing minorities to more dangerous outcomes than majority group members (Kahn & Davies, 2011). Driving behaviors are likely influenced by driver’s implicit attitudes, as driving and stopping decisions are often fast paced, rife with distractions, and consciously or sub-consciously initiated. The result of this process may be differential stopping behavior based on pedestrian race.

Download full version (PDF): Racial Bias in Driver Yielding Behavior at Crosswalks

About the Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning

www.pdx.edu/usp

“Our mission is to assist in the development of healthy communities through an interdisciplinary program of teaching, research and public service. Faculty and students engage the intellectual, policy and practice aspects of urban studies and planning from the local to the international levels and actively participate in the analysis, development and dissemination of the innovations for which Portland and the Pacific Northwest are known.”

Tags: Arizona, Arlie Adkins, AZ, Kimberly Barsamian Kahnb, OR, Oregon, Pedestrian, Pedestrian Safety, Portland, Portland State University, Tara Goddarda, Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Arizona

RSS Feed

RSS Feed