BROOKINGS INSTITUTE

Introduction

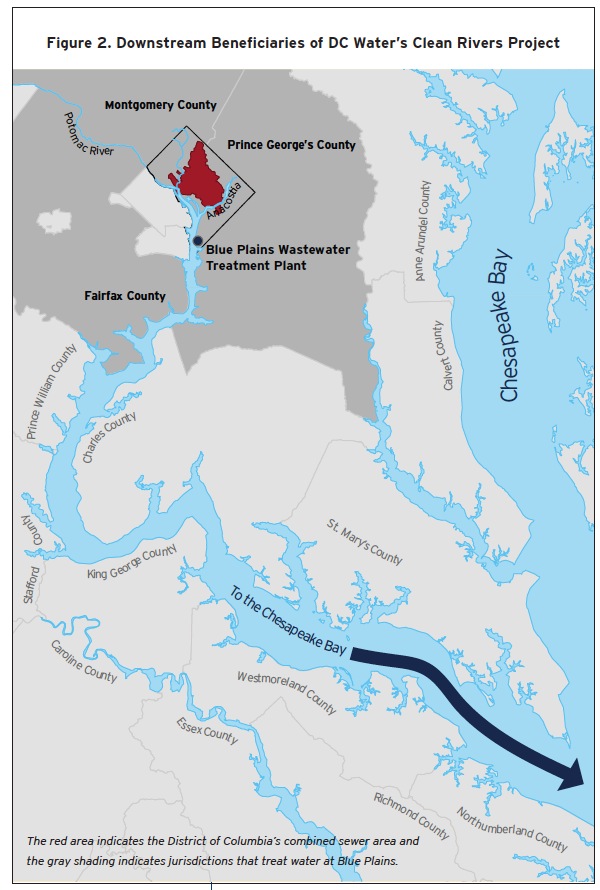

The nation’s capital, like other older American cities, is partially served by a combined sewer system (CSS) in which pipes carry both storm water and sewage or waste water. In dry weather, waste water flows to the Blue Plains Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant at the southern tip of the District along the Potomac River. After heavy rains, however, the capacity of the combined sewer is often exceeded, and a mixture of sewage an storm water—combined sewer overflows (CSOs)—discharges into the Anacostia and Potomac rivers and Rock Creek, leading ultimately to downstream destinations, including the Chesapeake Bay.

Both storm water and waste water present serious water quality challenges. Storm water is dirty, no matter how it is conveyed. It picks up oil, grease, sediment, and animal waste from streets, gardens, and roofs and sends it untreated to surrounding waterways. Prolonged development has increased the amount of surface areas—rooftops, roadways, and parking lots—that do not absorb water. These impervious surfaces increase the runoff of storm water and snowmelt, making the clean water task more urgent, as well as causing erosion and other environmental problems. Untreated sewage leads to multiple problems: it compromises the safety of drinking water, makes water unfit for swimming or fishing, and causes offensive odors. Actions to improve water quality must address both storm water and waste water, but this paper focuses on sewage in storm water, specifically the need to identify fair and sustainable options to pay for the very expensive infrastructure improvements already underway to reduce CSOs.

Washington’s sewers date back to the nineteenth century, when the federal government built an 80-mile CSS that still survives today. Most of what Americans think of as the federal government—the Capitol, the Supreme Court, the Mall and museums, the major monuments, and the White House—lies in the oldest one-third of the city covered by the CSS. Separate storm sewers, which also are old, serve the remaining two-thirds of the city.

Today’s combined sewer overflows are the direct result of a federal decision in the nineteenth century to design, build, and then retain the combined sewers. The federal government was responsible for the District’s infrastructure until the institution of limited home rule in 1973. A recent study by D.C. Appleseed asserts that the original Army Corps design and construction of the CSO system has proved

“significantly defective,” with resulting damage to the regional watershed’s ecosystems.

Responsibility for water distribution, sewer pipes, and sewage treatment now rests with D.C. Water, formerly known as D.C. Water and Sewer Authority (WASA). D.C. Water is an independent authority with a regional board of directors appointed by the District; Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland; and Fairfax County in Virginia. In addition to serving the District and its residents, D.C. Water also serves the suburban counties represented on the board by treating waste water at Blue Plains from these jurisdictions. A separate entity, the Department of the Environment (DDOE), is responsible for the city’s separate sewer system, which covers two-thirds of the city and channels storm water only, and not waste water. The somewhat complicated relationship between D.C. Water and the DDOE is discussed in Appendix A.

The District’s status as the nation’s capital significantly reduces its tax base and fiscal capacity. Previous analysis has addressed the fiscal constraints imposed on the District by its lack of a state and the special relationship between the District and the federal government.4 A high proportion of property and sales are exempt from taxation (government, diplomatic, educational, nonprofits, among others). Congress prohibits the District from taxing the earnings of workers living in the suburbs and working in the city. The city’s high poverty rates and long-term population decline (recently reversed for the first time in decades) further erode the tax base, limiting the city’s ability to meet its fiscal needs, including the ability to maintain and improve its infrastructure. When serious mismanagement and economic downturn led to financial crisis in the 1990s, the federal government imposed a Financial Authority, which balanced the budget and restored fiscal solvency. Throughout this period, the District suffered from restricted spending and, often, further deferrals of needed maintenance, capital replacement and modernization of infrastructure.

Recognizing the need for a long-term solution, President Clinton in 1997 proposed a Revitalization Act to help address the underlying structural causes of the District’s fiscal crisis. Highly visible needs, as well as the significant limits and constraints on the city’s ability to fund capital projects, led Clinton to include a National Capital Infrastructure Authority (NCIA) to fund $1.4 billion in repairs and construction. Unfortunately, it did not survive into the final Revitalization Act.

However, a 2008 report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recognized the strong case for federal investment in infrastructure, such as the Clean Rivers Project, whose benefits “accrue to broad geographic areas and are not restricted to a class of users that can be charged more directly.” The CBO specifically cited as an example “wastewater treatment plants for communities whose water eventually flows into a major resource such as the Chesapeake Bay.”

Download full report (PDF): Cleaner Rivers for the National Capital Region: Sharing the Cost

About Brookings Institution

www.brookings.edu

“The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, DC. Our mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations that advance three broad goals:

* Strengthen American democracy;

* Foster the economic and social welfare, security and opportunity of all Americans and

* Secure a more open, safe, prosperous and cooperative international system.

Brookings is proud to be consistently ranked as the most influential, most quoted and most trusted think tank.”

Tags: Brookings Institute, CBO, Congressional Budget Office, Washington DC

RSS Feed

RSS Feed